Mastering Python File I/O: How to Read and Write Files Easily

Introduction

A tiny Python script was reading a CSV every morning, updating a report, and exiting. No errors. No warnings. Everyone trusted it. Weeks later, someone noticed the numbers drifting. Not wildly wrong—just slightly off. Enough to be dangerous.

The code hadn’t changed. The data hadn’t changed. What had changed was time.

The script opened files the way most tutorials still teach:

f = open("data.csv")Sometimes the file didn’t close. Sometimes the encoding guessed wrong. Sometimes the script exited early and left things half-done. Nothing dramatic enough to fail loudly. Just enough to fail quietly.

That’s the problem with most file-handling examples you find online. They don’t break on day one. They break on day forty-two—when no one is watching, and everyone assumes Python “already handled it.”

File handling in Python isn’t hard. What’s outdated is the way it’s usually explained. Patterns that were fine for throwaway scripts are still being passed around as best practice, even though Python itself has moved on.

This post is not about memorizing functions or copying boilerplate. It’s about learning a modern, low-friction way to read and write files—one that works the same for text, JSON, and CSV files, and doesn’t make you think about cleanup, encoding, or path weirdness every time.

If file I/O has ever felt fragile, annoying, or slightly cursed, this is for you. We’ll keep the mental load light and the patterns consistent—and by the end, file handling will be the most boring (and reliable) part of your Python code.

Why File Handling in Python Still Goes Wrong in 2026

Python has changed a lot. The way many people learn file handling hasn’t.

If you search for “read file in python” today, you’ll still find examples that look like they were written for a different era—small scripts, single-machine setups, and data that never leaves ASCII. They work just enough to pass a demo, and that’s exactly why the problems stick around.

The danger isn’t obvious failure.

The danger is code that appears correct while slowly collecting risk.

The Copy-Paste Trap in Python File Handling

Most file-handling bugs don’t start with bad intentions. They start with a search result.

A beginner looks up how to read a file, copies the first snippet, and moves on. That snippet often uses patterns that were once common but are no longer ideal—manual open(), no encoding, and cleanup that relies on memory or luck.

The problem is scale.

Tutorials are usually written for tiny examples, but real projects aren’t tiny for long. Code gets reused. Scripts turn into jobs. Jobs turn into pipelines. And the old patterns quietly follow along.

Beginners don’t inherit bad code.

They inherit old assumptions—that files will always close, that encodings will behave, that the environment will stay the same.

Hidden Problems No One Warns You About

File handling issues rarely announce themselves.

Sometimes a file stays open just a little too long. Sometimes an exception jumps out before cleanup runs. Sometimes a file created on one machine suddenly throws encoding errors on another.

These problems don’t always crash your program. They show up as:

- missing rows

- partially written files

- strange characters that “weren’t there before”

The script runs. The output exists. And yet something is off.

That’s what makes file I/O tricky. When it fails quietly, you don’t get feedback—you get false confidence.

Why “It Works” Is Not the Same as “It’s Safe”

A script that works on your laptop is not the same as code that survives real usage.

Local scripts are forgiving. Production environments are not. Files get bigger. Paths change. Processes overlap. Errors happen at the worst possible moment.

Unsafe file handling doesn’t always explode. It leaks. It degrades. It creates bugs that only appear after the code has been trusted.

Modern Python already solved most of these problems—but only if you stop using file-handling patterns designed for a different time.

That’s why the next section isn’t about more complexity.

It’s about a simpler mental model that avoids these issues by default—before they ever show up.

The Modern Python File Handling Mindset

Before touching code, the real upgrade happens in how you think about files.

Most file-handling problems don’t come from missing syntax. They come from treating files like ordinary variables—open them, use them, forget about them. That mental model worked when scripts were small and short-lived. It breaks the moment code sticks around.

Modern Python nudges us toward a better way.

Files Are Resources, Not Variables

A variable lives safely inside memory.

A file lives outside your program.

It belongs to the operating system. It has limits. It can be locked, interrupted, partially written, or left hanging if something goes wrong. That’s why files need rules.

The mental shift is simple:

when you open a file, you’re borrowing a resource.

Borrowed things need to be returned—every time, even when something unexpected happens. Cleanup isn’t an optional extra; it’s part of correct behavior. If cleanup depends on you remembering to do it, it will eventually be forgotten.

Modern Python assumes this reality and gives you tools that make cleanup automatic instead of hopeful.

The Modern Stack for Reading and Writing Files in Python

You don’t need more libraries. You need better defaults.

The modern approach rests on three ideas that work together quietly:

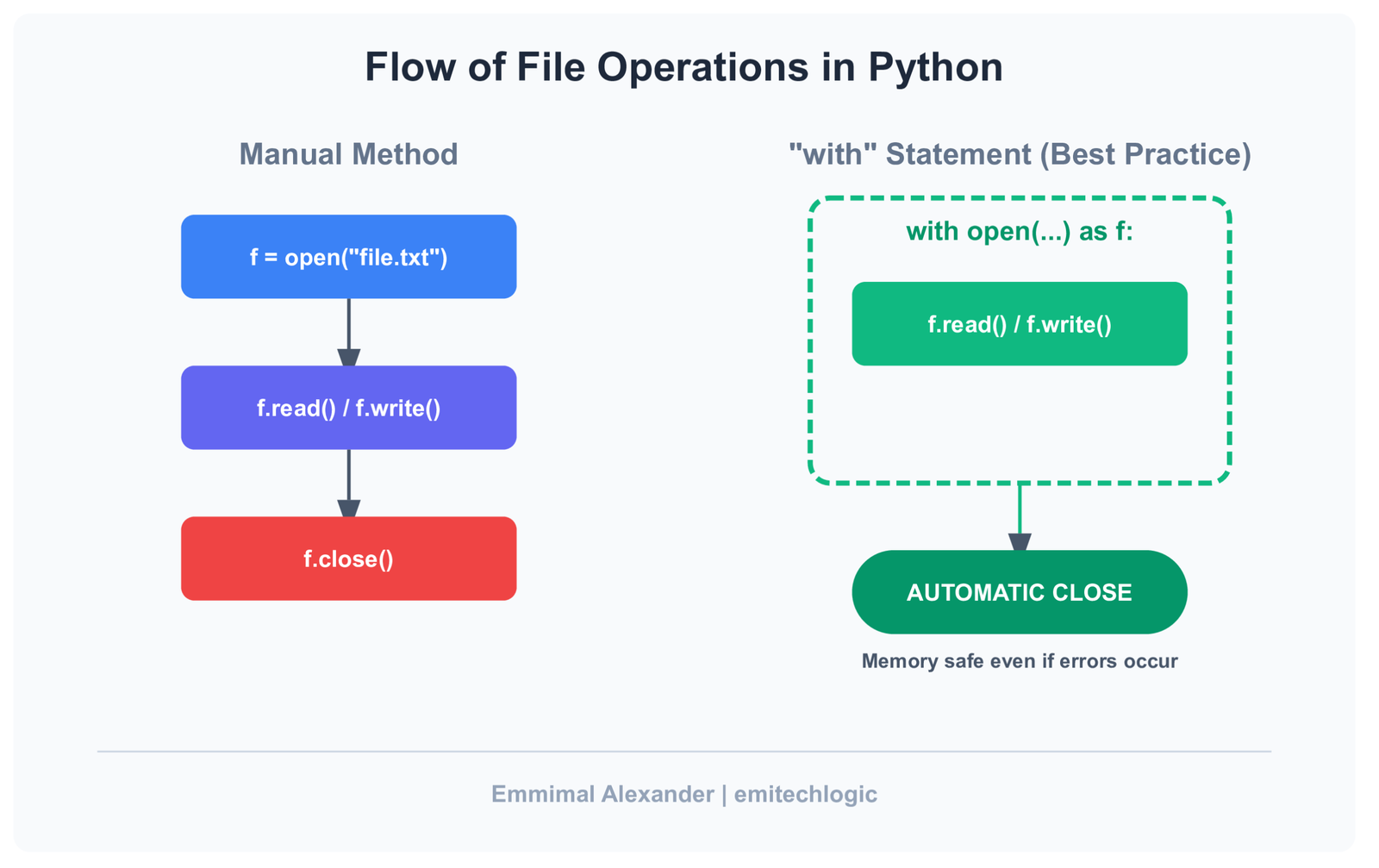

- Context managers (

with)

They define a clear beginning and end. When the block ends, Python cleans up—no matter how it ends. pathlib.Path

Paths become objects with meaning, not strings you have to juggle. They work the same across systems and read like intent, not plumbing.- Format-aware tools (

json,csv)

Structured data should be handled by tools that understand structure. Parsing by hand is where subtle bugs are born.

None of this is flashy. That’s the point.

Why This Stack Scales From Scripts to Real Projects

This approach holds up because it removes decisions you shouldn’t have to make repeatedly.

There’s less room for accidental mistakes.

Code reviews get easier because intent is obvious.

The same patterns work whether you’re writing a five-line script or a long-running service.

Most importantly, the code stops depending on discipline and starts depending on design.

With the mindset in place, the code itself becomes almost boring—and that’s exactly what you want when files are involved.

Now let’s put this into practice, starting with the simplest case: reading a plain text file the modern way.

Reading Files in Python the Clean Way

Reading a file shouldn’t feel like a negotiation with your future self. It should be obvious, safe, and predictable. That’s the standard modern Python aims for—and it’s why the old patterns are slowly being pushed aside.

Let’s start with the baseline every file operation should build on.

Reading a Text File in Python Using Pathlib

This is the simplest, cleanest way to read a text file today:

from pathlib import Path

path = Path("notes.txt")

with path.open(encoding="utf-8") as file:

content = file.read()

print(content)

A few important things are happening here, even though the code looks quiet:

- The path works the same on Windows, macOS, and Linux

- The encoding is explicit, not guessed

- The file is guaranteed to close when the block ends

You’re not juggling strings or worrying about cleanup. You’re just stating intent: read this file.

That consistency matters more than it seems. When every file read follows the same pattern, your brain stops tracking edge cases and starts focusing on logic.

Why This Pattern Replaces f = open()

The older approach isn’t “wrong”—it’s just fragile.

Manual open() relies on discipline. You have to remember to close the file. You have to hope no error interrupts the flow. You have to trust that encoding won’t surprise you later.

This pattern removes all of that:

- Automatic cleanup – files close even when errors occur

- Better readability – the lifecycle of the file is visible at a glance

- Built-in safety – fewer ways to misuse the file object

It’s not more code. It’s less responsibility.

Want a quick interview-ready reference?

Download the Python File Handling Cheat Sheet — a compact summary you can revise in minutes.

Download ImageReading Large Files Without Breaking Memory

Calling .read() loads the entire file into memory. That’s fine for small files. It’s a bad idea for large ones.

When file size is unknown—or obviously large—you read line by line instead:

from pathlib import Path

path = Path("large_log.txt")

with path.open(encoding="utf-8") as file:

for line in file:

process(line)

This approach keeps memory usage stable, no matter how big the file gets. Python streams the data instead of swallowing it whole.

As a rule of thumb:

- Use

.read()for small, controlled files - Iterate line by line for logs, exports, or anything that can grow

The key isn’t memorizing rules—it’s choosing patterns that fail gracefully when conditions change.

With reading covered, writing files becomes a natural extension of the same idea. Let’s move there next.

Writing Files in Python Without Accidental Data Loss

Writing files is where confidence turns into regret.

Most data loss doesn’t happen because Python is unreliable. It happens because writing files feels too easy. One wrong mode, one forgotten detail, and yesterday’s data is gone—quietly replaced by today’s test run.

The fix isn’t paranoia. It’s being intentional.

Writing Text Files Safely in Python

When you open a file for writing, you’re making a decision—whether you realize it or not.

from pathlib import Path

path = Path("report.txt")

with path.open("w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

file.write("Daily report generated.\n")

That "w" matters. It means overwrite. If the file exists, it’s replaced. If it doesn’t, it’s created.

This is perfectly safe when it’s intentional.

It’s dangerous when it’s accidental.

Modern file handling makes that intent visible. Anyone reading the code knows exactly what will happen. No surprises hidden three lines later.

Appending to Files Without Corrupting Data

Appending feels safer because it doesn’t delete anything. But it has its own traps.

with path.open("a", encoding="utf-8") as file:

file.write("Another entry added.\n")

Append is perfect for:

- logs

- incremental exports

- audit trails

It’s dangerous when:

- the file format expects strict structure

- multiple processes write at the same time

- old data should not mix with new

Appending to a CSV or JSON file blindly can leave you with data that looks valid—but isn’t.

The key question is simple:

Should this file represent a moment, or a history?

Moment → overwrite

History → append

The One Habit That Prevents 80% of File Writing Bugs

This isn’t about memorizing APIs. It’s about two habits that remove most risk upfront.

- Always use

with

If the file lifecycle isn’t visible, something will go wrong eventually. - Always set encoding

If you don’t choose one, the environment will choose for you—and you won’t like the result.

These two lines of discipline eliminate entire classes of bugs without adding complexity.

Once writing feels predictable, handling structured formats like JSON and CSV stops being intimidating. It becomes the same pattern, just with better tools.

Working With JSON Files in Python (The Right Way)

JSON is where “quick scripts” start becoming long-term commitments.

At first, it’s just a config file. Then it’s cached data. Then it’s something another service depends on. The problem isn’t JSON itself—it’s treating JSON files like plain text and hoping structure survives.

Python already knows how to handle JSON properly. The trick is letting it.

Reading JSON Files in Python Without Manual Parsing

If a file contains JSON, don’t read it as a string and parse it later. Let Python do both steps together.

from pathlib import Path

import json

path = Path("config.json")

with path.open(encoding="utf-8") as file:

data = json.load(file)

print(data)

This does exactly what you want:

- Opens the file safely

- Parses the JSON correctly

- Returns native Python objects

No string juggling. No guessing where parsing should happen. One clear operation.

Writing JSON Files That Humans Can Actually Read

Machines don’t care how JSON looks. Humans do.

Writing JSON without formatting works—but it makes files painful to inspect, debug, or version-control. A small option fixes that.

settings = {

"theme": "dark",

"autosave": True,

"timeout": 30

}

with path.open("w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

json.dump(settings, file, indent=2)

That indent=2 isn’t decoration. It’s future-proofing.

The output becomes:

- predictable

- readable

- stable across edits

Which means fewer conflicts and fewer “what changed here?” moments.

Common JSON File Handling Mistakes in Python

These mistakes show up everywhere—and they’re easy to avoid once you notice them.

- Using

json.loads()on files.loads()expects a string, not a file. If you’re opening a file, you want.load(). - Writing raw strings to JSON files

Manually constructing JSON strings is fragile. One missing quote, one trailing comma, and the file breaks.

Treat JSON as structured data, not formatted text. Once you do, JSON files stop being a source of stress and start behaving like reliable building blocks.

Next, we’ll apply the same thinking to CSV files—the format everyone underestimates until it bites back.

Practical CSV File Handling in Python (Real-World Example)

CSV files are deceptively simple. They show up everywhere—exports from tools, reports from finance, data someone downloaded from Excel five minutes ago. They look easy, which is why they cause so many subtle bugs.

The goal with CSVs isn’t clever code. It’s predictable behavior.

Reading CSV Files in Python Using DictReader

When reading CSV files, the biggest mistake is relying on column positions. Index-based access works until someone adds a column, reorders fields, or saves the file slightly differently.

DictReader avoids that entire class of problems.

from pathlib import Path

import csv

path = Path("users.csv")

with path.open(encoding="utf-8", newline="") as file:

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

rows = list(reader)

print(rows)

Instead of lists, you get dictionaries:

{'id': '1', 'name': 'Alice', 'email': 'alice@example.com', 'active': 'true'}

Column names beat indexes because they survive change. This approach also plays nicely with Excel-generated files, which often include headers whether you want them or not.

Writing Clean CSV Files in Python

Writing CSVs is where small omissions create big headaches.

output = Path("active_users.csv")

with output.open("w", encoding="utf-8", newline="") as file:

writer = csv.DictWriter(

file,

fieldnames=["id", "name", "email"]

)

writer.writeheader()

writer.writerows(rows)

Three things matter here:

- Headers

Always write them. CSVs without headers confuse both humans and tools. - Field order

Make it explicit. Don’t rely on dictionary ordering for clarity. - Newline handling

newline=""prevents extra blank lines—especially on Windows.

Why CSV Bugs Usually Come From Tiny Details

CSV issues rarely look dramatic. They show up as “almost right” data.

Extra blank lines that appear only on certain systems.

Missing headers that break downstream imports.

Numbers treated as strings because assumptions were never checked.

None of these problems are complex. They’re just easy to overlook.

The pattern stays the same: use tools that understand the format, be explicit about intent, and let Python handle the fussy parts.

With CSVs covered, the final pieces are about resilience—handling missing files, unexpected paths, and the edges where real-world scripts tend to break.

Handling Missing Files and Paths Gracefully in Python

Most file-handling tutorials assume the happy path: the file exists, the folder is there, and everything behaves. Real code doesn’t get that luxury.

Files go missing. Paths change. Directories don’t exist yet. And when those cases aren’t handled deliberately, scripts fail in ways that feel unnecessary.

Graceful handling isn’t about adding a lot of checks—it’s about using the tools Python already gives you.

Checking If a File Exists Using Pathlib

Before reading or overwriting a file, it’s often worth asking a simple question: does this file actually exist?

from pathlib import Path

path = Path("data.json")

if path.exists():

print("Something is there")

if path.is_file():

print("And it’s a file, not a directory")

The distinction matters. .exists() tells you something is at that path. .is_file() confirms it’s the thing you expect.

This avoids errors that only show up when a directory is accidentally treated like a file—or when a missing file crashes a long-running job.

Creating Files and Folders Safely

Creating directories by hand is another place where small assumptions cause failures.

output_dir = Path("outputs/reports")

output_dir.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

parents=True creates the full path if it doesn’t exist.exist_ok=True avoids crashing if it already does.

This combination makes your code resilient without being defensive or noisy.

About race conditions: checking for existence and then creating a directory in two separate steps can fail under concurrency. Letting mkdir() handle it atomically is safer and simpler.

The pattern is the same as everything else in this post:

state intent, let Python enforce it, and avoid fragile manual checks.

With these edge cases handled, we can now tie everything together in a small, realistic end-to-end example—reading data, transforming it, and writing it back out cleanly.

A Simple End-to-End Example (Read → Transform → Write)

This is where everything clicks. Not isolated snippets—one small flow you could actually drop into a project.

Problem Statement

You receive a CSV export every day.

It contains user data.

You need to clean it slightly and store it as JSON for another system.

Nothing fancy. Just real work.

- Input: a CSV file

- Transform: keep only active users, normalize fields

- Output: a clean, readable JSON file

Complete Python Script

Here’s the full script—minimal, readable, and built entirely on the patterns you’ve seen so far.

from pathlib import Path

import csv

import json

# Paths

input_csv = Path("users.csv")

output_json = Path("active_users.json")

# Read CSV

with input_csv.open(encoding="utf-8", newline="") as file:

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

users = list(reader)

# Transform data

active_users = []

for user in users:

if user.get("active") == "true":

active_users.append({

"id": int(user["id"]),

"name": user["name"],

"email": user["email"]

})

# Write JSON

with output_json.open("w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

json.dump(active_users, file, indent=2)

That’s it.

Breaking Down the End-to-End Script (What’s Actually Happening)

This script does three things, in order:

- reads data from a CSV file

- transforms that data into a cleaner structure

- writes the result to a JSON file

Each part is intentionally separated so nothing feels tangled.

Imports: Only What We Actually Need

from pathlib import Path

import csv

import json

Pathhandles file paths in a clean, cross-platform waycsvunderstands CSV structure (columns, headers, rows)jsonhandles structured data safely

Defining Paths Up Front

input_csv = Path("users.csv")

output_json = Path("active_users.json")

Paths are defined once and reused. This matters more than it looks.

When file paths are scattered through code, changes become risky. Centralizing them makes the script easier to read, change, and review.

Reading the CSV File

with input_csv.open(encoding="utf-8", newline="") as file:

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

users = list(reader)

This block does three things at once:

- opens the file safely

- reads each row as a dictionary (column names → values)

- closes the file automatically when done

Using DictReader means we never depend on column positions. If someone reorders columns in the CSV, the script keeps working.

At this point, users is a list of dictionaries—plain Python data.

Transforming the Data

active_users = []

for user in users:

if user.get("active") == "true":

active_users.append({

"id": int(user["id"]),

"name": user["name"],

"email": user["email"]

})

This is the heart of the script.

- We filter only active users

- We normalize fields

- Convert types deliberately

Notice what’s not happening here:

- file access

- format logic

- no side effects

This separation is intentional. Transformation logic stays easy to test and reason about.

Writing the JSON Output

with output_json.open("w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

json.dump(active_users, file, indent=2)

This final step turns clean Python data into clean JSON.

- The file is opened intentionally for writing

- Encoding is explicit

indent=2makes the output readable and stable

Once the block ends, the file is safely closed—no matter what.

Each step does one thing:

- file handling stays at the edges

- transformation logic stays in the middle

Why This Pattern Holds Up Over Time

This structure ages well for a few simple reasons.

It’s easy to modify.

Want to add a field? Change one dictionary.

Want a different output format? Swap the writer, not the logic.

It’s easy to test.

You can test the transformation separately from file I/O. You can feed in fake data without touching the filesystem.

Most importantly, it’s easy to reason about.

When something goes wrong, you know where to look.

This is what “modern file handling” really means—not new APIs, but clean boundaries and predictable behavior.

From here, file handling stops being a risk factor and starts being just another solved problem in your codebase.

File Handling Habits That Will Save You Later

This section isn’t about syntax.

It’s about habits—the kind that don’t matter today, but quietly decide whether your code survives six months from now.

Most file-handling pain comes from small shortcuts that felt reasonable at the time. These habits remove those shortcuts entirely.

Always Be Explicit With Encoding

If you don’t choose an encoding, your environment will.

That might be your operating system.

Or the machine running your code next month.

Or a container with very different defaults.

The result is the same: characters that worked yesterday suddenly don’t.

Being explicit costs almost nothing:

path.open(encoding="utf-8")

And it buys you predictability. You stop debugging “weird symbols” and start trusting your files again.

Never Parse Structured Data as Plain Text

If the file has a format, let the format handle it.

JSON is not a string with braces.

CSV is not “just commas.”

Manually splitting lines or constructing strings feels faster—until one edge case breaks everything. Quoted commas, escaped characters, missing fields… those details exist whether you handle them or not.

Python already solved these problems. Use the tools that understand structure instead of re-implementing it imperfectly.

Treat File I/O as a Boundary, Not Logic

File access should sit at the edges of your code—not inside your core logic.

When reading, do it once.

When writing, do it once.

Everything in between should operate on plain Python data.

This habit makes your code:

- easier to test

- easier to change

- easier to reason about

Most importantly, it keeps file handling from spreading through your codebase like glue.

When you adopt these habits, file I/O stops being a source of uncertainty. It becomes a solved problem—quiet, predictable, and safely out of your way.

That’s where you want it.

When to Break These Rules (Yes, Sometimes You Should)

Rules are useful because they remove decisions.

But good engineers know why the rules exist—and when bending them makes sense.

File handling is no different.

Quick Scripts vs Long-Running Systems

If you’re writing a throwaway script to rename a few files or inspect some data once, perfection isn’t the goal. Speed is.

In those cases, you might:

- skip abstraction

- inline a file read

- accept a little duplication

That’s fine—as long as the script stays a script.

Problems start when quick code quietly becomes important code. A cron job. A shared tool. Something other people depend on. That’s when shortcuts turn into liabilities.

A good rule of thumb:

- One-off script → optimize for speed of writing

- Anything recurring → optimize for clarity and safety

The danger isn’t breaking the rules. It’s forgetting you did.

Performance Tradeoffs You Should Actually Care About

Most file-handling “optimizations” don’t matter.

Worrying about microseconds while reading a config file is wasted energy. Using unsafe patterns for imaginary speed gains usually costs more in debugging time later.

The performance decisions that do matter are bigger and rarer:

- streaming large files instead of loading them entirely

- avoiding repeated disk access inside loops

- choosing the right format for the job

Until you hit those limits, clarity beats cleverness.

Modern file-handling patterns are fast enough for almost all use cases. When they aren’t, you’ll know—and you’ll have real data to justify changing them.

Breaking the rules is allowed.

Breaking them accidentally is what hurts.

That’s the difference experience makes.

Must Read

- Why sorted() Is Safer Than list.sort() in Production Python Systems

- Monotonic Sequence in Python: 7 Practical Methods With Edge Cases, Interview Tips, and Performance Analysis

- How to Check if Dictionary Values Are Sorted in Python

- Check If a Tuple Is Sorted in Python — 5 Methods Explained

- How to Check If a List Is Sorted in Python (Without Using sort()) – 5 Efficient Methods

Common File Handling Bugs You’ll Eventually Hit in Python

These aren’t beginner mistakes.

They’re the kind of bugs that survive code reviews, pass tests, and show up later when no one remembers touching the file logic.

Let’s look at a few.

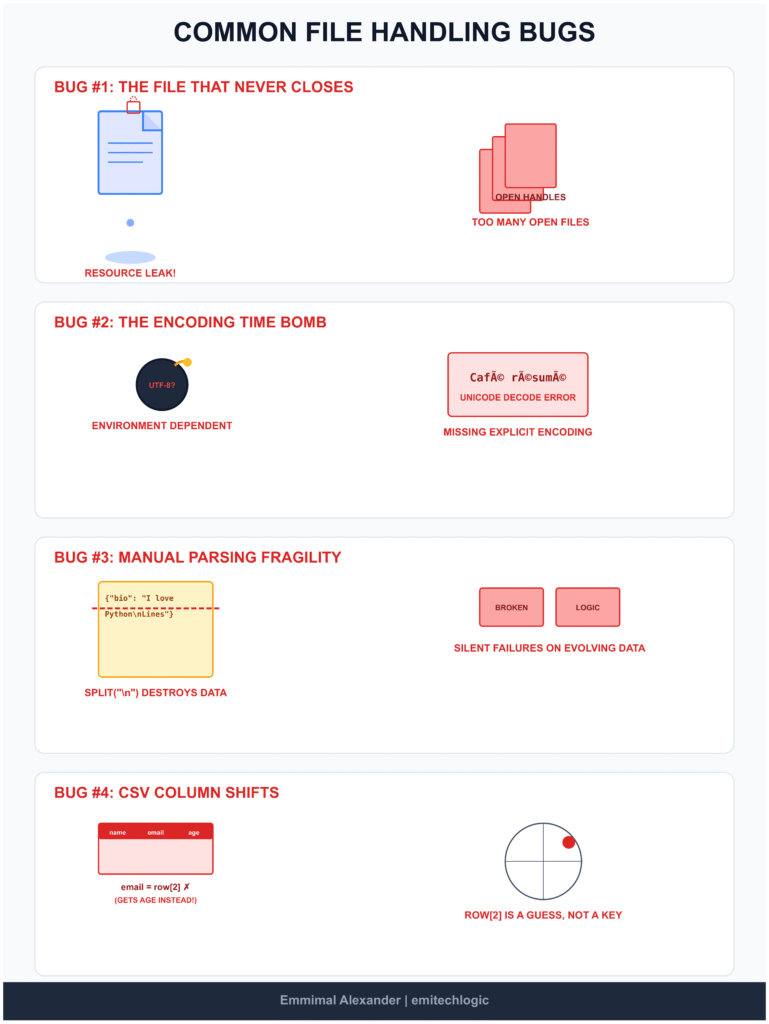

Spot the Bug #1: The File That Never Quite Closes

f = open("data.txt")

data = f.read()

Nothing looks wrong here. The file opens. The content loads. Life is good.

Now ask yourself one question:

What happens if the next line throws an exception?

The file stays open.

In small scripts, this is easy to ignore. In real programs, this slowly becomes:

- leaked file descriptors

- locked files on Windows

- random “too many open files” errors

Why this bug survives:

It doesn’t fail loudly. It fails politely.

The fix

from pathlib import Path

with Path("data.txt").open(encoding="utf-8") as f:

data = f.read()

The file is closed automatically. Even if everything goes wrong.

Spot the Bug #2: The Encoding Time Bomb

with open("users.txt") as f:

data = f.read()

This works. Until it doesn’t.

The moment someone saves that file with a different encoding—or runs your script on another machine—you get errors that feel random and hard to reproduce.

Why this bug survives:

It depends on the environment, not the code.

The fix

from pathlib import Path

with Path("users.txt").open(encoding="utf-8") as f:

data = f.read()

Explicit encoding turns a hidden assumption into a visible decision.

Spot the Bug #3: Parsing Structured Data as Plain Text

data = open("config.json").read()

settings = data.split("\n")

This might “work” for now. It’s also fragile.

The moment formatting changes—or a value contains a newline—your logic quietly breaks.

Why this bug survives:

It passes tests until the file evolves.

The fix

import json

from pathlib import Path

with Path("config.json").open(encoding="utf-8") as f:

settings = json.load(f)

Let the format handle itself. That’s what it exists for.

Spot the Bug #4: The CSV That Shifts Under Your Feet

import csv

with open("users.csv") as f:

reader = csv.reader(f)

for row in reader:

email = row[2]

This works… until someone reorders the columns.

Then you’re emailing the wrong people.

Why this bug survives:

Indexes don’t explain themselves.

The fix

import csv

from pathlib import Path

with Path("users.csv").open(encoding="utf-8", newline="") as f:

reader = csv.DictReader(f)

for row in reader:

email = row["email"]

Names survive change. Positions don’t.

The Pattern Behind All These Bugs

Notice something?

None of these are “syntax mistakes.”

They’re assumption bugs.

- Assuming files close themselves

- Assuming encodings match

- Assuming formats stay simple

- Assuming structure never changes

Modern Python file handling is mostly about removing assumptions, not adding complexity.

If you fix these few patterns, file-related bugs stop being mysterious—and start being rare.

Try It Yourself: Run the Code Live

Reading code is helpful, but running it makes the behavior obvious. Use the embedded editor below to execute the Python example, tweak the logic, and observe how the output changes — no local setup required.

Tip: Modify the input values and re-run the code to test edge cases.

Closing Thoughts

File handling shouldn’t be impressive.

It should be boring, predictable, and forgettable.

If reading and writing files still feels fragile, it’s usually not because Python is lacking—it’s because old habits keep sneaking in. Once you switch to a modern baseline—with blocks, Pathlib, and format-aware tools—most file-related bugs simply stop appearing.

Not because you’re being clever.

Because you’ve removed assumptions.

That’s the quiet win here.

If this post changed even one small habit—adding an explicit encoding, stopping index-based CSV access, or never opening a file outside a context manager—then it’s already doing its job.

This site is about building software that holds up over time, not collecting clever snippets. If that mindset resonates with you, you’re exactly where you should be.

See you in the next one.

Want a quick interview-ready reference?

Download the Python File Handling Cheat Sheet — a compact summary you can revise in minutes.

Download ImagePython File Handling Quiz

Test your knowledge of modern file handling practices

External Resources

Python Official Documentation – File I/O

https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/inputoutput.html#reading-and-writing-files

This section of the Python documentation provides a detailed overview of how to read from and write to files, including examples and best practices.

Python Official Documentation – json Module

https://docs.python.org/3/library/json.html

This resource explains the JSON module in Python, covering how to encode and decode JSON data, and provides examples of reading and writing JSON files

FAQ

How do I read a file in Python?

The safest and most modern way to read a file in Python is by using a context manager (with) and Pathlib. This ensures the file is always closed properly, even if an error occurs.

from pathlib import Path

with Path("data.txt").open(encoding="utf-8") as f:

content = f.read()

This approach avoids resource leaks and works consistently across operating systems.

How do I write to a file in Python safely?

To write to a file safely in Python, always use a with block and specify the file mode explicitly ("w" to overwrite, "a" to append).

from pathlib import Path

with Path("output.txt").open("w", encoding="utf-8") as f:

f.write("Safe file writing in Python\n")

Using a context manager guarantees the file is closed properly and prevents partial writes or locked files.

Is Pathlib better than open()?

open()?Yes—Pathlib is generally better than using open() directly, especially in modern Python code.

Pathlib:

- Makes paths more readable

- Handles file paths consistently across platforms

- Works cleanly with context managers

You still use open(), but through Path.open(), which leads to clearer and safer file-handling code.

How do I handle CSV files in Python?

The recommended way to handle CSV files in Python is with the built-in csv module, combined with Pathlib.

import csv

from pathlib import Path

with Path("users.csv").open(encoding="utf-8", newline="") as f:

reader = csv.DictReader(f)

for row in reader:

print(row["email"])

Using DictReader is safer than relying on column positions and helps prevent bugs when CSV structures change.

Leave a Reply