Global and Local Variables in Python: A Complete Guide

Python Global and Local Variables: Complete Tutorial with Interactive Examples

Master Python variable scope with hands-on coding examples. Learn the difference between global and local variables, understand variable shadowing, and practice with our interactive code playground.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Python Variables

- What Are Variables Really?

- Local Variables Explained

- Global Variables Explained

- Global vs Local Variables

- The global Keyword

- Advanced Concepts

- Interactive Code Playground

- Common Variable Patterns

- Troubleshooting Common Errors

- Interactive Quiz

- Frequently Asked Questions

- 13. External Resources

Introduction to Python Variables

Python variables can be confusing when you start coding. Some variables work everywhere in your code. Others only work in specific places. This happens because of something called variable scope.

Think about your house. You have a private bedroom where you keep personal stuff. Only you can access it. You also have a living room where everyone hangs out. Anyone in the house can use it.

Python variables work the same way. Local variables are like your bedroom – private and restricted. Global variables are like the living room – everyone can access them.

Understanding this concept will change how you write Python code. Your programs will have fewer bugs. Your code will be easier to read. You’ll avoid common mistakes that trip up new programmers.

Variables have a lifespan and a place where they work. This is called their scope and lifetime. Once you master this, you control how your code behaves.

What This Guide Covers

- How Python stores and manages variables

- Local variables and where they live

- Global variables and when to use them

- Common mistakes and how to avoid them

- Real examples with detailed explanations

- Interactive practice questions

A Simple Example to Start

Look at this code. Can you guess what it will print?

# This example shows variable scope in action

name = "Alice" # This is a global variable

def greet():

name = "Bob" # This is a local variable

print(f"Inside function: Hello, {name}!")

greet()

print(f"Outside function: Hello, {name}!")

What Python prints:

Inside function: Hello, Bob! Outside function: Hello, Alice!

Let’s break down what happens step by step:

- Line 2: Python creates a global variable called “name” and stores “Alice” in it

- Line 4: We define a function called “greet”

- Line 5: Inside the function, Python creates a NEW local variable also called “name” and stores “Bob”

- Line 6: The print statement uses the LOCAL “name” variable, so it prints “Bob”

- Line 8: We call the greet() function

- Line 9: This print statement is OUTSIDE the function, so it uses the GLOBAL “name” variable and prints “Alice”

Notice something important here. We have two variables with the same name “name”. But they live in different places. Python keeps them completely separate. The local variable “Bob” stays inside the function. The global variable “Alice” stays outside.

This behavior lets you reuse variable names without conflicts. Each function can have its own workspace. Think of it like having a notebook in your room and another notebook in the kitchen – same purpose, different locations.

What Are Variables Really?

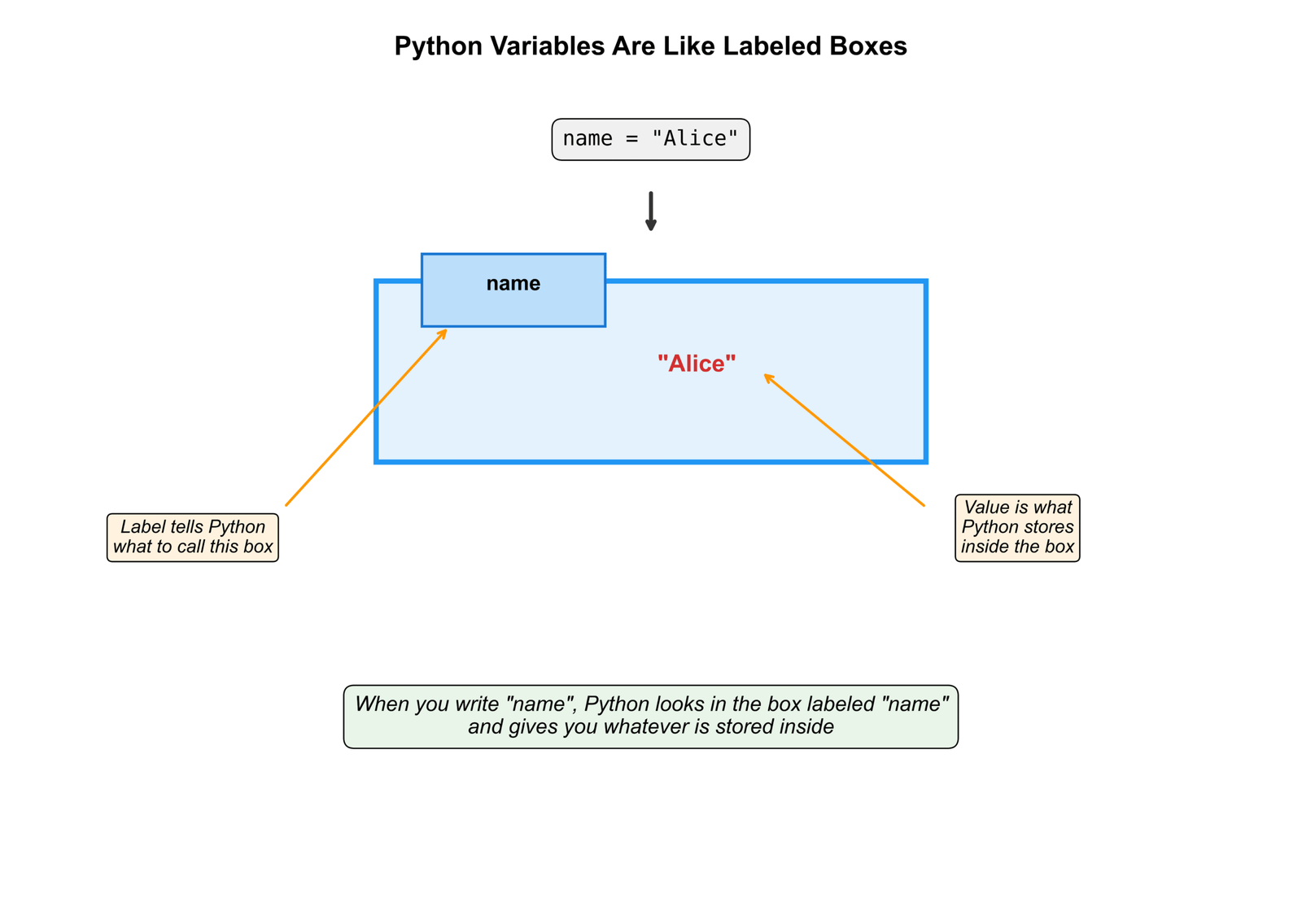

Variables are containers that hold information. When you create a variable, Python sets aside space in memory to store your data. Every variable has a name and a value.

Think of variables like labeled storage containers. When you write age = 25, Python creates a container labeled “age” and puts the number 25 inside it.

Click image to open in new tab – Python variables work like labeled boxes

Creating Your First Variables

Let’s create some variables and see how Python handles them. Each variable will store different types of information.

# Creating different types of variables

student_name = "Emma" # Text (string)

student_age = 16 # Number (integer)

student_height = 5.4 # Decimal number (float)

is_student = True # True/False (boolean)

# Print each variable to see what's stored

print("Student name:", student_name)

print("Student age:", student_age)

print("Student height:", student_height, "feet")

print("Is student:", is_student)

Python prints this:

Student name: Emma Student age: 16 Student height: 5.4 feet Is student: True

Let’s understand each line of this code:

- Line 2: Creates a string variable. Strings hold text and are wrapped in quotes

- Line 3: Creates an integer variable. Integers are whole numbers (no decimal point)

- Line 4: Creates a float variable. Floats are numbers with decimal points

- Line 5: Creates a boolean variable. Booleans can only be True or False

- Lines 7-10: Print statements show us what’s stored in each variable

Python automatically figures out what type of data you’re storing. You don’t need to tell it “this is a number” or “this is text” – it just knows based on what you put in the variable.

Interactive Variable Memory Demo

Click on the variables below to see how Python stores different data types:

Each variable holds exactly what we put in it. Python remembers the name and value of every variable you create. When you type the variable name, Python finds the right container and gives you what’s inside.

How Python Manages Memory

Python automatically manages memory for your variables. You don’t need to worry about allocating or freeing space. When you create a variable, Python finds room for it. When you’re done with it, Python cleans it up.

This automatic memory management makes Python easier to use than languages like C or C++. You can focus on solving problems instead of managing memory.

Different data types take different amounts of space. Integers use less memory than long text strings. Python handles these details automatically. Sometimes you need to check what type a variable is or convert one type to another using type casting.

Pro Tip: Variable Naming

Use descriptive names for your variables. Instead of writing:

x = "John Doe"

Write something clear like:

customer_name = "John Doe"

This makes your code self-documenting. Anyone can understand what the variable stores just by reading its name.

Local Variables Explained

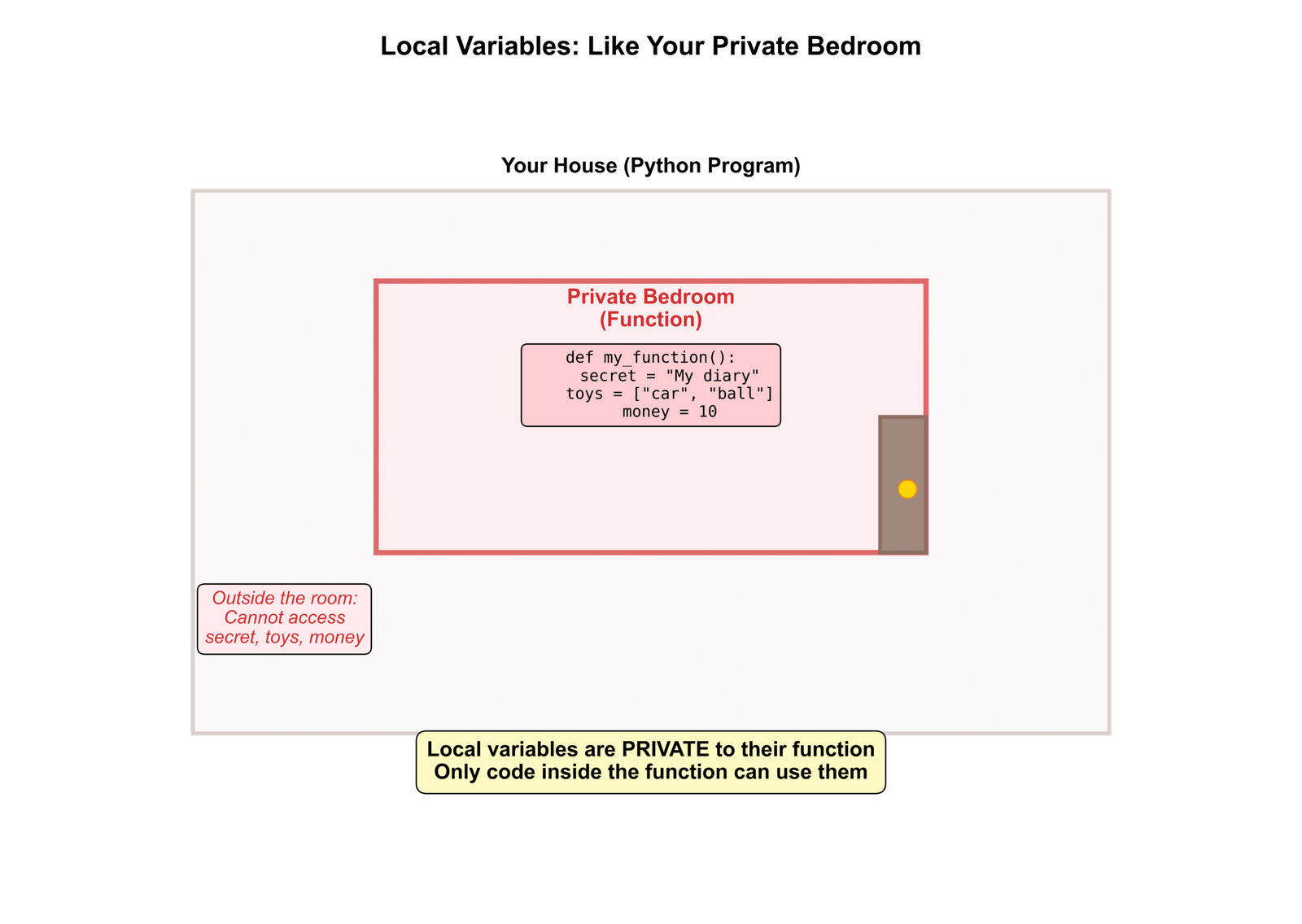

Local variables live inside functions. Think of them as private storage that only the function can access. When you create a variable inside a function, it becomes local to that function.

The word “local” means “in this specific place only.” These variables exist only while the function runs. Once the function finishes, Python deletes these variables from memory.

Click image to open in new tab – Local variables are like your private bedroom

A Real Local Variable Example

Let’s create a function that calculates the area of a rectangle. All variables inside this function will be local variables.

def calculate_rectangle_area():

length = 10 # Local variable - only exists in this function

width = 5 # Local variable - only exists in this function

area = length * width # Local variable - calculated from other locals

print(f"Length: {length}")

print(f"Width: {width}")

print(f"Area: {area}")

return area

# Call the function and store the result

result = calculate_rectangle_area()

print(f"The function returned: {result}")

# Try to access local variables outside the function

# These lines would cause errors if uncommented:

# print(length) # NameError: name 'length' is not defined

# print(width) # NameError: name 'width' is not defined

Code Walkthrough

Here’s what happens when this code runs:

- Line 1: We define a function named “calculate_rectangle_area”

- Lines 2-4: Inside the function, we create three local variables

- Line 4: We calculate area by multiplying length × width (10 × 5 = 50)

- Lines 6-8: We print the values to see what we calculated

- Line 10: We return the area value so the outside code can use it

- Line 13: We call the function and store its return value in “result”

- Line 14: We print the result to confirm everything worked

The commented lines (16-18) show what would happen if we tried to use the local variables outside the function – Python would give us an error!

When you run this code, Python prints:

Length: 10 Width: 5 Area: 50 The function returned: 50

Notice how length, width, and area only work inside the function. The function can use them freely. But outside the function, these variables don’t exist anymore.

What Happens When You Try to Access Local Variables Outside

Python will give you a NameError if you try to use local variables outside their function. Here’s what that looks like:

def create_message():

greeting = "Hello there!" # Local variable

name = "Python learner" # Local variable

message = greeting + " " + name # Local variable

print(message)

create_message()

# This will cause an error:

print(greeting) # Python doesn't know what 'greeting' is

Python shows this error:

Hello there! Python learner NameError: name 'greeting' is not defined

The function ran perfectly and printed its message. But when we tried to use ‘greeting’ outside the function, Python complained. That variable only existed inside the function.

Why Local Variables Matter

Local variables give each function its own workspace. This prevents functions from accidentally changing each other’s data. When you work with function parameters and return values in Python, local variables help keep everything organized.

Important Facts About Local Variables

- Created when the function starts running

- Only accessible within their function

- Automatically deleted when the function ends

- Each function call creates fresh local variables

- Cannot interfere with variables in other functions

- Help prevent naming conflicts between functions

When you start writing your own functions, local variables become your best friend. Each function operates in its own bubble, which keeps everything organized.

Interactive Scope Demonstration

Watch how variables exist in different scopes:

Clean Code Tip: Function Parameters

Instead of using global variables to pass data to functions, use parameters:

# Bad approach - using global variables

total = 0

def add_numbers():

global total

total = 5 + 3

# Better approach - using parameters and return values

def add_numbers(a, b):

return a + b

result = add_numbers(5, 3)

The second approach is cleaner because the function is self-contained. You can test it easily and reuse it anywhere.

Global Variables Explained

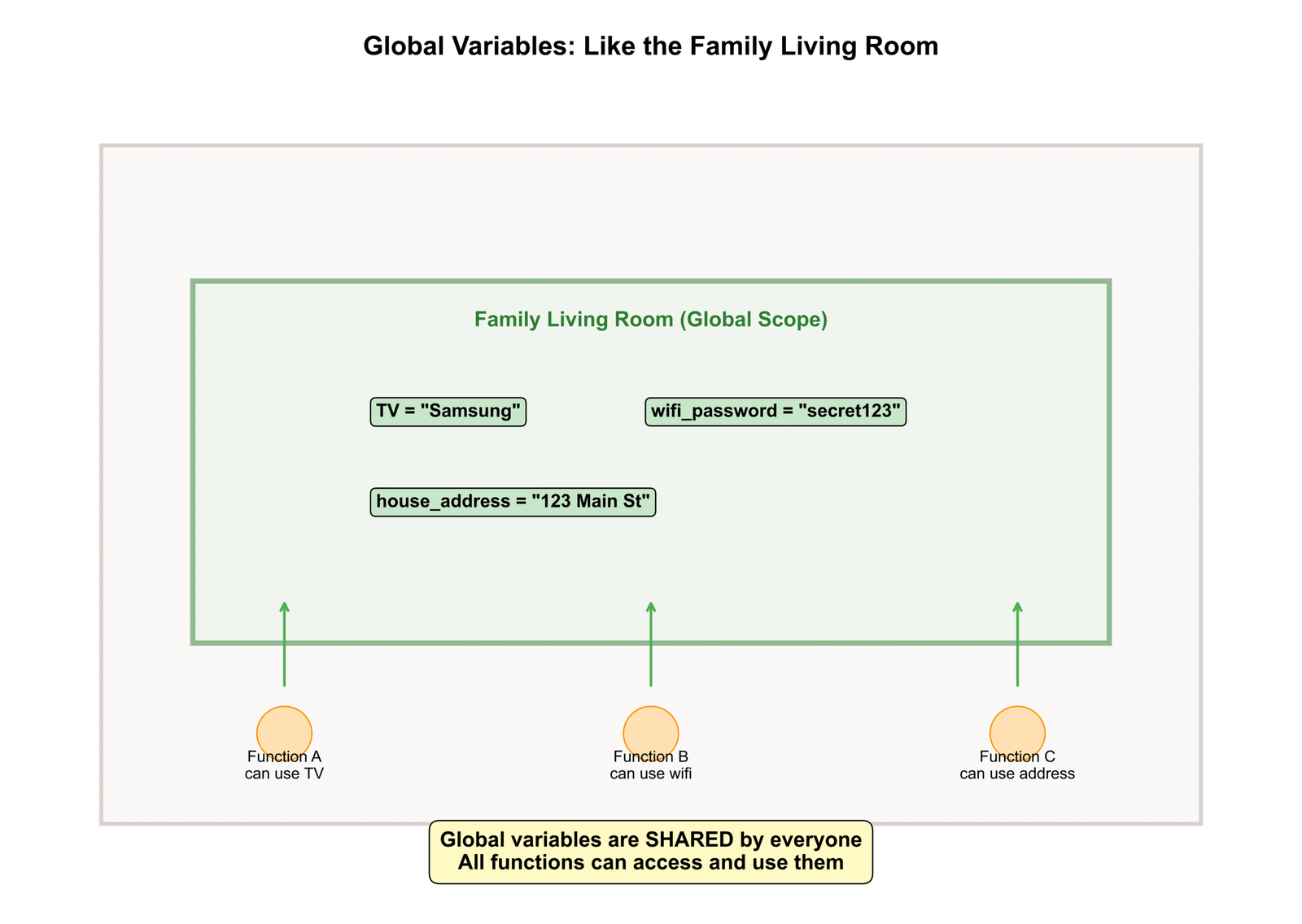

Global variables are like shared storage that every part of your program can access. When you create a variable outside any function, it becomes global. Every function in your program can read and use these variables.

Think of global variables as items in your kitchen that everyone in the house can use. The coffee maker, microwave, and refrigerator are available to anyone who needs them.

Click image to open in new tab – Global variables are like the shared family living room

Creating and Using Global Variables

Let’s create some global variables and see how different functions can access them. Notice how we define these variables outside any function.

# These are global variables - defined outside any function

app_name = "Student Tracker"

max_students = 30

current_students = 0

school_year = 2024

def display_app_info():

# This function can read all global variables

print(f"Application: {app_name}")

print(f"School Year: {school_year}")

print(f"Maximum Students: {max_students}")

print(f"Current Students: {current_students}")

def calculate_available_spots():

# This function also uses global variables

available = max_students - current_students

return available

def show_status():

spots_left = calculate_available_spots()

print(f"Spots available: {spots_left}")

# Use global variables directly in main program

print(f"Welcome to {app_name}")

print(f"Running for school year {school_year}")

# Call functions that use global variables

display_app_info()

show_status()

Python outputs:

Welcome to Student Tracker Running for school year 2024 Application: Student Tracker School Year: 2024 Maximum Students: 30 Current Students: 0 Spots available: 30

All three functions could access the global variables without any special code. Python automatically makes global variables available everywhere in your program.

Reading vs Modifying Global Variables

Functions can read global variables easily. But modifying them requires special syntax. We’ll cover that in the next section. For now, remember that reading global variables works automatically.

Best Uses for Global Variables

Global variables work best for data that multiple parts of your program need:

- Application settings and configuration

- Constants that never change

- Database connection information

- User preferences

- Version numbers and app metadata

As your programs grow bigger, good naming habits save you hours of debugging time. Clear variable names are like road signs – they guide you through your code.

Modern Python Shortcut: F-strings

Notice how we use f-strings in our examples? This is the modern way to format text in Python:

# Old way (still works, but verbose)

print("Application: " + app_name)

print("Year: " + str(school_year))

# Modern way (clean and readable)

print(f"Application: {app_name}")

print(f"Year: {school_year}")

Why f-strings are better:

- No need to convert numbers to strings manually

- No messy string concatenation with + signs

- Much easier to read, especially with multiple variables

- Faster execution than the old methods

Just put ‘f’ before the quote and wrap variables in curly braces {}. Python handles the rest automatically.

A Practical Global Variable Example

Here’s a realistic example showing how global variables help organize program data:

# Game configuration - global variables

GAME_TITLE = "Number Guessing Game"

MAX_ATTEMPTS = 5

WINNING_SCORE = 100

current_attempts = 0

def show_game_intro():

print(f"Welcome to {GAME_TITLE}")

print(f"You have {MAX_ATTEMPTS} attempts to guess the number")

print(f"Win {WINNING_SCORE} points if you succeed!")

def check_attempts_remaining():

remaining = MAX_ATTEMPTS - current_attempts

print(f"Attempts remaining: {remaining}")

return remaining > 0

# Start the game

show_game_intro()

check_attempts_remaining()

Output:

Welcome to Number Guessing Game You have 5 attempts to guess the number Win 100 points if you succeed! Attempts remaining: 5

Notice how we used capital letters for constants (GAME_TITLE, MAX_ATTEMPTS, WINNING_SCORE) and lowercase for variables that might change (current_attempts). This follows Python conventions and makes the code clearer.

Global vs Local Variables: Understanding the Differences

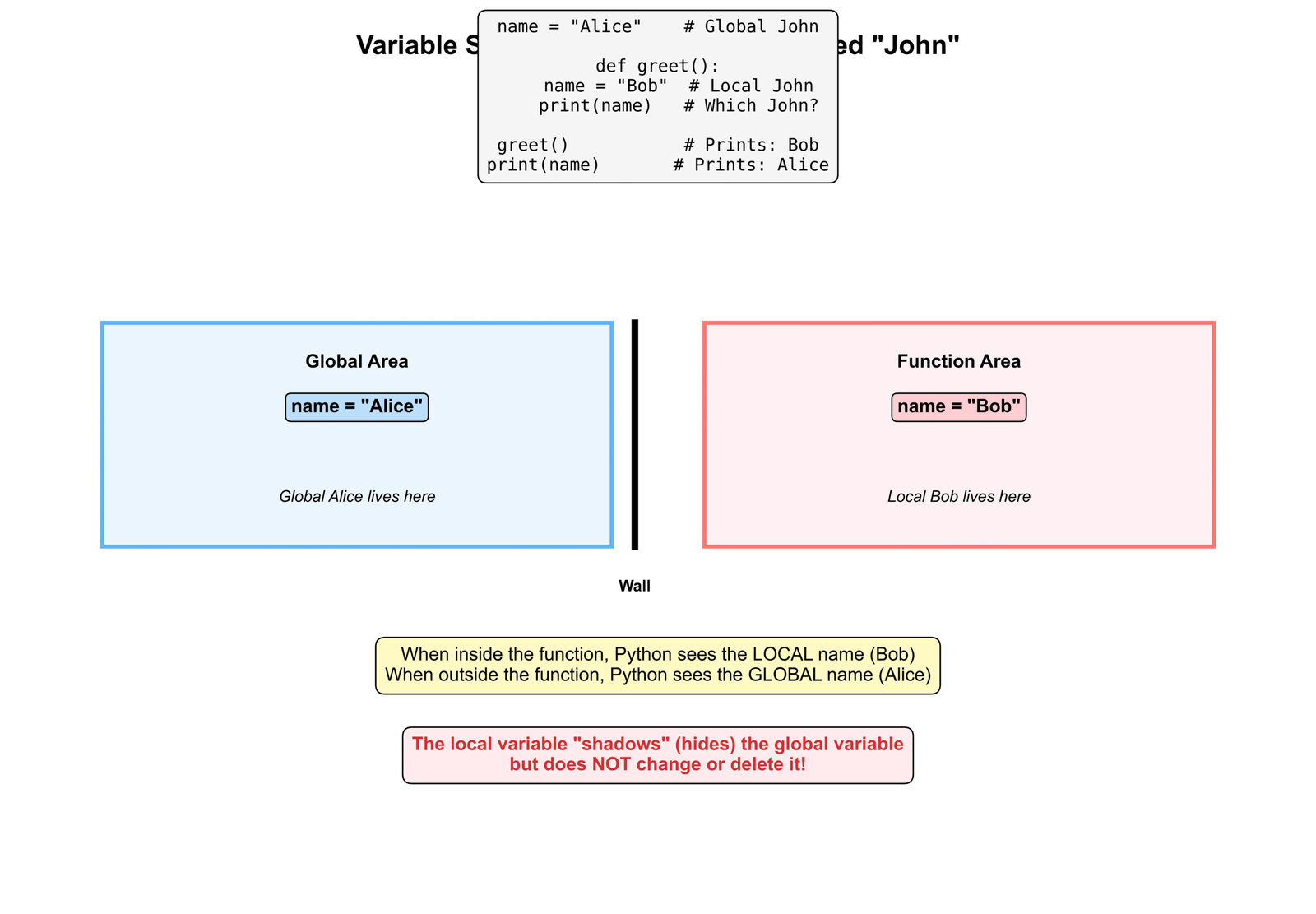

What happens when you have global and local variables with the same name? This is where things get interesting. Python has rules for deciding which variable to use.

Side-by-Side Comparison

| Feature | Local Variables | Global Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Where Created | Inside functions | Outside functions |

| Accessibility | Only within function | Everywhere in program |

| Lifetime | Until function ends | Entire program |

| Memory Usage | Freed automatically | Stays in memory |

| Best For | Temporary calculations | Settings, constants |

| Safety | Cannot interfere with other functions | Can be changed by any function |

Variable Shadowing Example

Here’s what happens when global and local variables have the same name. This behavior might surprise you:

# Global variable

score = 100

def play_game():

# Local variable with the same name as the global

score = 50

print(f"Score inside function: {score}")

# Add some points to the local score

score = score + 25

print(f"Updated score inside function: {score}")

# Let's see what happens

print(f"Score before function: {score}")

play_game()

print(f"Score after function: {score}")

Python prints:

Score before function: 100 Score inside function: 50 Updated score inside function: 75 Score after function: 100

The global variable “score” remained 100 throughout. The function created its own local “score” variable. Changes to the local variable didn’t affect the global one.

This behavior is called “variable shadowing.” The local variable casts a shadow over the global variable inside the function. The global variable still exists, but the function can’t see it.

Click image to open in new tab – Variable shadowing is like having two people with the same name

How Python Finds Variables

Python searches for variables in a specific order. This order determines which variable gets used when names match:

- Local scope – variables inside the current function

- Enclosing scope – variables in outer functions (for nested functions)

- Global scope – variables at the module level

- Built-in scope – Python’s built-in names like print, len, str

Python stops searching once it finds a variable with the right name. This search order is called LEGB rule (Local, Enclosing, Global, Built-in).

A More Complex Example

Let’s see how this works with multiple functions and variables:

# Global variables

player_name = "Alex"

health = 100

def start_battle():

# Local variables that shadow globals

player_name = "Warrior Alex"

energy = 50 # This is purely local - no global equivalent

print(f"Player: {player_name}")

print(f"Health: {health}") # This uses the global health

print(f"Energy: {energy}")

def check_status():

# This function sees the original globals

print(f"Outside battle - Player: {player_name}")

print(f"Outside battle - Health: {health}")

start_battle()

check_status()

Output:

Player: Warrior Alex Health: 100 Energy: 50 Outside battle - Player: Alex Outside battle - Health: 100

Notice how start_battle() used its local player_name but the global health. The check_status() function saw the original global variables since it had no local ones to shadow them.

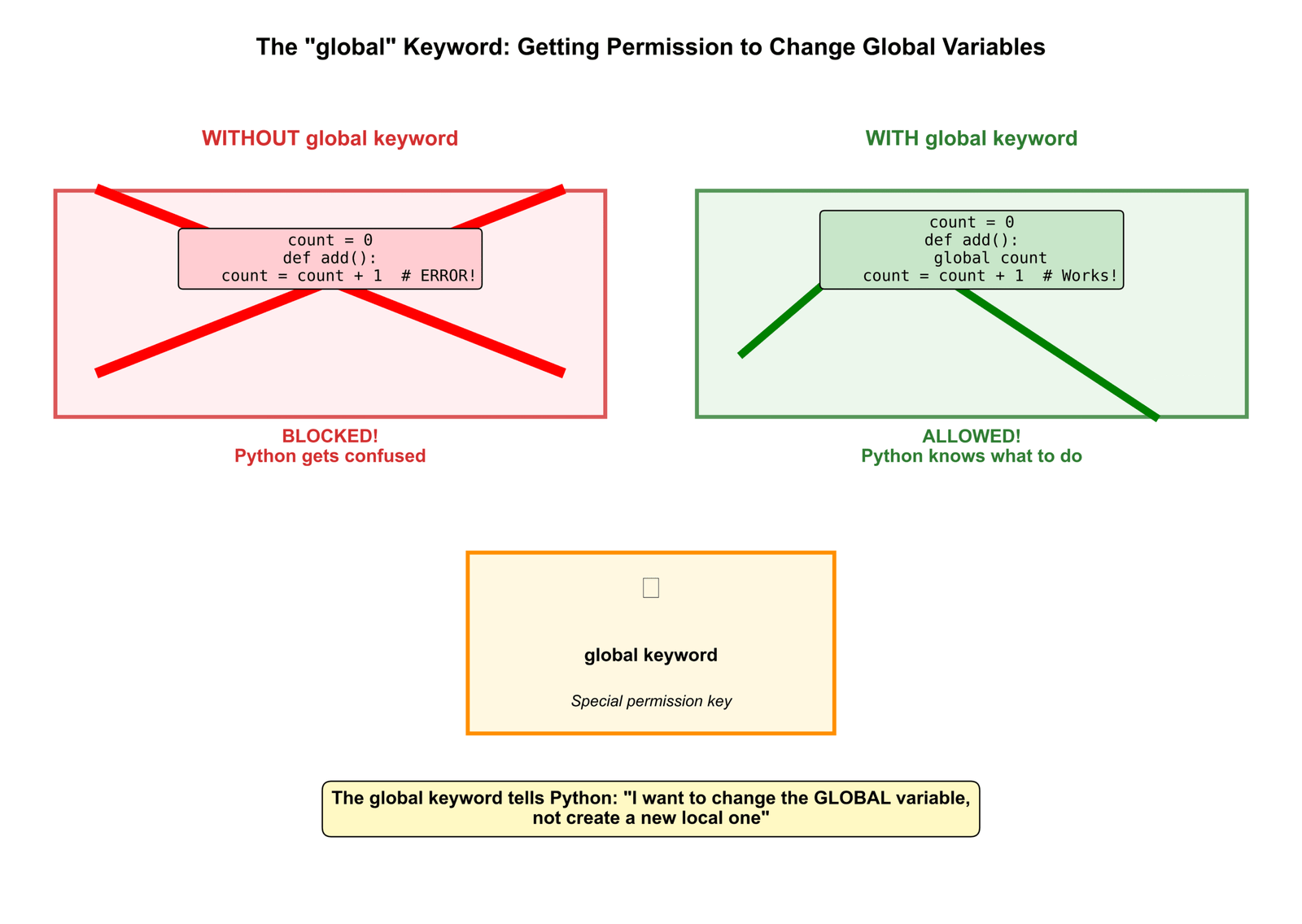

The global Keyword: Modifying Global Variables

Sometimes you need to change a global variable from inside a function. Python won’t let you do this normally. But the global keyword gives you permission to modify global variables from within functions.

Why You Need the global Keyword

Without the global keyword, Python gets confused when you try to modify a global variable. Let’s see what happens:

# Global variable

total_points = 0

def add_points():

# This will cause an error

total_points = total_points + 10

print(f"Points: {total_points}")

# This will break

add_points()

Python shows this error:

UnboundLocalError: local variable 'total_points' referenced before assignment

Python sees you trying to assign to total_points. It assumes you want to create a local variable. But then you’re trying to use total_points before creating it. This creates confusion.

Click image to open in new tab – The global keyword is like getting permission to change global variables

Using global to Fix the Problem

The global keyword tells Python “use the global variable, don’t create a local one.” Here’s how it works:

# Global variable

total_points = 0

def add_points():

global total_points # Tell Python to use the global variable

total_points = total_points + 10

print(f"Points after adding: {total_points}")

def subtract_points():

global total_points # Use global here too

total_points = total_points - 5

print(f"Points after subtracting: {total_points}")

def show_points():

# Reading doesn't need global keyword

print(f"Current points: {total_points}")

# Test the functions

show_points()

add_points()

add_points()

subtract_points()

show_points()

Understanding the global Keyword

Let’s break down what the global keyword does:

- Without global: Python thinks you want to create a new local variable

- With global: Python knows you want to modify the existing global variable

Why show_points() doesn’t need global: Because it only reads the variable, it doesn’t change it. Reading global variables works automatically.

Pro tip: You can declare multiple global variables in one line: global var1, var2, var3

Python outputs:

Current points: 0 Points after adding: 10 Points after adding: 20 Points after subtracting: 15 Current points: 15

Notice that show_points() doesn’t need the global keyword. Reading global variables works automatically. You only need global when you want to modify them.

A Real-World Example

Here’s a practical example using global variables to track game state:

# Game state variables

player_level = 1

player_experience = 0

experience_needed = 100

def gain_experience(amount):

global player_experience, player_level, experience_needed

player_experience += amount

print(f"Gained {amount} experience!")

# Check if player leveled up

if player_experience >= experience_needed:

player_level += 1

player_experience = 0

experience_needed = experience_needed + 50

print(f"Level up! Now level {player_level}")

def show_player_stats():

print(f"Level: {player_level}")

print(f"Experience: {player_experience}/{experience_needed}")

# Play the game

show_player_stats()

gain_experience(30)

gain_experience(40)

gain_experience(35) # This should cause a level up

show_player_stats()

Game output:

Level: 1 Experience: 0/100 Gained 30 experience! Gained 40 experience! Gained 35 experience! Level up! Now level 2 Level: 2 Experience: 5/150

This game example shows how global variables work with function parameters and return values to build interactive programs. The functions take input (amount of experience) and update the global game state.

Quick Debugging Trick

Add print statements to see which variables are global vs local:

def debug_variables():

local_var = "I'm local"

print(f"Locals: {locals()}")

print(f"Globals contain 'player_level': {'player_level' in globals()}")

debug_variables()

This technique helps you understand what’s happening in your code when variables aren’t behaving as expected.

Best Practices with global

When to Use global

- Counters that track things across function calls

- Settings that need updates during program execution

- Game state that multiple functions must modify

- Application configuration that changes

When NOT to Use global

- For values you can pass as parameters instead

- For temporary calculations

- When only one function needs the data

- For values that functions can return instead

Advanced Concepts

The nonlocal Keyword

Python has another keyword called nonlocal. This works with nested functions – functions inside other functions. It lets inner functions modify variables from their parent functions.

def create_counter():

count = 0 # Variable in the outer function

def increment():

nonlocal count # Access the outer function's variable

count += 1

return count

def decrement():

nonlocal count

count -= 1

return count

def get_count():

return count # Reading doesn't need nonlocal

print(f"Starting count: {get_count()}")

print(f"After increment: {increment()}")

print(f"After increment: {increment()}")

print(f"After decrement: {decrement()}")

print(f"Final count: {get_count()}")

create_counter()

Python prints:

Starting count: 0 After increment: 1 After increment: 2 After decrement: 1 Final count: 1

The nonlocal keyword tells Python “use the variable from the parent function, not a global variable and not a new local variable.” This creates a middle ground between local and global scope.

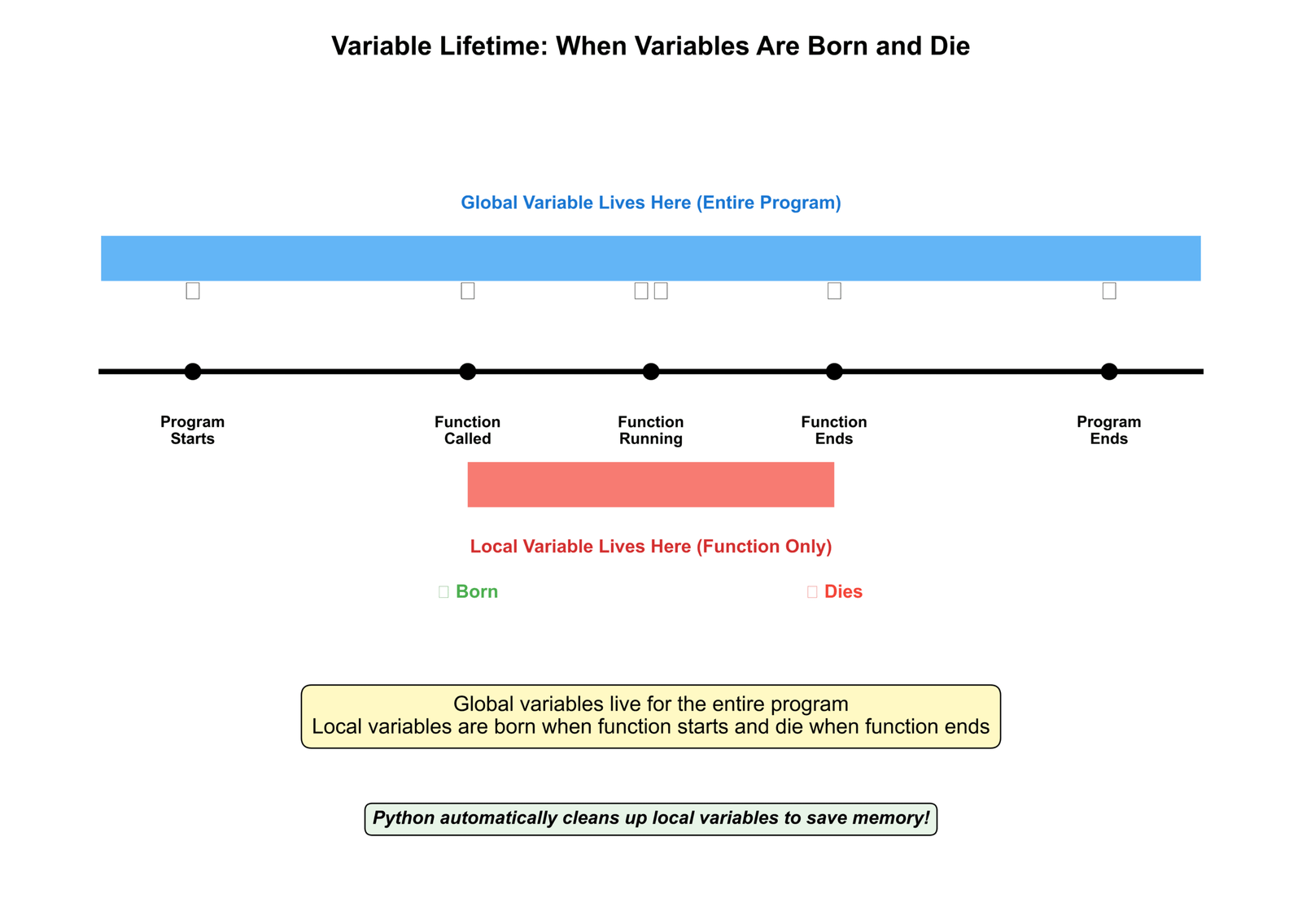

Variable Lifetime and Memory

Variables have lifetimes – periods when they exist in memory. Understanding this helps you write efficient programs and avoid bugs.

Click image to open in new tab – Variable lifetime shows when variables are born and die

Loop variables behave differently from regular variables. In Python loops, the loop variable stays alive even after the loop ends, which can surprise beginners.

Loop Variable Gotcha

Here’s something that catches many beginners off guard:

for i in range(3):

print(f"Loop iteration: {i}")

print(f"After loop, i still exists: {i}") # This works!

# Output:

# Loop iteration: 0

# Loop iteration: 1

# Loop iteration: 2

# After loop, i still exists: 2

What’s happening here:

- range(3) creates numbers 0, 1, 2

- Each number gets stored in variable ‘i’ one at a time

- After the loop ends, ‘i’ still contains the last value (2)

- You can still use ‘i’ outside the loop

This is different from languages like C++ where loop variables disappear. In Python, loop variables stick around.

Best practice: Don’t rely on loop variables after the loop ends. It can confuse other programmers reading your code.

def demonstrate_variable_lifetime():

print("Function starts - variables don't exist yet")

# Variables are created when first assigned

name = "Demo Function"

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

total = 0

print(f"Variables created: {name}")

# Loop variable also has a lifetime

for num in numbers:

total += num

# 'num' exists during each loop iteration

print(f"Loop finished. Total: {total}")

print(f"Loop variable 'num' still exists: {num}") # Last value

return total

# When function ends, ALL local variables are destroyed

result = demonstrate_variable_lifetime()

print(f"Function returned: {result}")

print("All function variables are now destroyed")

Output shows variable lifetime:

Function starts - variables don't exist yet Variables created: Demo Function Loop finished. Total: 15 Loop variable 'num' still exists: 5 Function returned: 15 All function variables are now destroyed

Notice that the loop variable ‘num’ keeps its last value until the function ends. This is different from some other programming languages.

The globals() and locals() Functions

Python provides built-in functions to examine variables in different scopes:

# Global variables

app_name = "Variable Explorer"

version = "2.0"

def explore_variables():

# Local variables

function_name = "explore_variables"

local_count = 42

print("=== LOCAL VARIABLES ===")

local_vars = locals()

for name, value in local_vars.items():

print(f" {name}: {value}")

print("\n=== GLOBAL VARIABLES ===")

global_vars = globals()

for name, value in global_vars.items():

if not name.startswith('__'): # Skip Python internals

print(f" {name}: {value}")

explore_variables()

Variables inspection output:

=== LOCAL VARIABLES === function_name: explore_variables local_count: 42 === GLOBAL VARIABLES === app_name: Variable Explorer version: 2.0 explore_variables: <function explore_variables at 0x...>

These functions help you debug programs and understand what variables exist at any point in your code.

Variable Scope in Different Contexts

Variable scope works differently in various Python constructs. Understanding these differences helps you write better code.

Don’t confuse programming variables with random variables in data science – those are mathematical concepts, not Python containers. Programming variables store data, while mathematical random variables represent uncertain outcomes.

When building programs that calculate mathematical sequences, proper variable scope keeps your calculations organized and prevents mix-ups between different parts of your computation.

Code Organization Tip

Group related variables together and use consistent naming patterns:

# Good organization - clear variable groups # User data user_name = "Alice" user_age = 25 user_email = "alice@example.com" # App settings app_version = "1.2.0" app_debug_mode = True app_max_users = 100 # Database config db_host = "localhost" db_port = 5432 db_name = "myapp"

This pattern makes your code much easier to read and maintain. Anyone can quickly understand what each variable group does.

Interactive Quiz

Test your understanding with these questions. Click on an answer to see if you’re right.

Frequently Asked Questions

Local variables solve several important problems:

- Memory efficiency: They get deleted automatically when not needed, saving memory

- Safety: Functions can’t accidentally mess up each other’s data

- Organization: Each function has its own clean workspace

- Reusability: Functions work independently and can be reused anywhere

- Debugging: Easier to track down problems when variables have limited scope

Too many global variables create chaos in large programs. Your code becomes harder to understand, test, and fix.

Yes, absolutely! This is called “variable shadowing.” The local variable creates a shadow over the global one inside the function. The global variable remains completely unchanged.

However, this can confuse people reading your code later. Use different names when possible to keep things clear.

Example: If you have a global variable called ‘count’, consider naming your local variable ‘local_count’ or ‘temp_count’ instead.

These keywords access variables from different scopes:

- global: Access variables from the top level of your file (module scope)

- nonlocal: Access variables from parent functions (enclosing scope)

Use ‘global’ when you need module-level variables. Use ‘nonlocal’ when working with nested functions and you need the outer function’s variables.

Use global variables sparingly. They work well for:

- Configuration settings (like database URLs or API keys)

- Constants that never change (like mathematical values)

- Application-wide state (like user preferences)

- Shared resources (like database connections)

Avoid global variables for temporary calculations, loop counters, or data that only one function needs. When in doubt, use local variables or function parameters instead.

No, functions cannot directly see local variables from other functions. Each function has its own private workspace that other functions cannot access.

Functions can share data through these methods:

- Global variables: Variables accessible to all functions

- Function parameters: Pass data when calling the function

- Return values: Get data back from the function

- Class attributes: Shared data in object-oriented programming

Each function call creates completely fresh local variables. When the function ends, Python destroys these variables. The next function call starts with brand new variables.

This means local variables have no memory between function calls. If you need variables to remember values between calls, use global variables or return the values and store them outside the function.

Yes, be careful not to use names like ‘print’, ‘len’, ‘str’, ‘list’, etc. These are Python’s built-in functions. If you create variables with these names, you’ll hide the built-in functions.

Example: Don’t write ‘list = [1, 2, 3]’ because then you can’t use the list() function anymore in that scope.

Use descriptive names like ‘student_list’ or ‘numbers’ instead.

Here are helpful debugging techniques:

- Use print() statements to check variable values at different points

- Use the locals() and globals() functions to see what variables exist

- Pay attention to NameError and UnboundLocalError messages

- Use a debugger to step through your code line by line

- Read error messages carefully – they often tell you exactly what’s wrong

Further Reading

Ready to dive deeper? These official Python documentation pages contain detailed technical information:

- The global Statement – Official Python Reference

- Naming and Binding – Python Execution Model

- Built-in Functions – Python Standard Library

These resources go much deeper into the technical details. Read them after you’re comfortable with the basics covered in this guide.

Summary and Final Thoughts

You now have a solid understanding of global and local variables in Python. This knowledge will help you write better, cleaner, and more reliable code.

What You’ve Mastered

- Local variables: Private to functions, automatically cleaned up, perfect for temporary work

- Global variables: Shared across your entire program, great for settings and constants

- Variable shadowing: How local variables can hide global ones with the same name

- The global keyword: Your tool for modifying global variables from within functions

- The nonlocal keyword: For working with nested functions and their parent variables

- LEGB rule: Python’s search order for finding variables

- Best practices: When to use each type of variable for maximum effectiveness

Your Next Steps

Now that you understand variable scope, practice these concepts:

- Write small programs using both local and global variables

- Experiment with the code examples from this guide

- Try creating nested functions with nonlocal variables

- Build a simple project that demonstrates proper variable scope

Smart programmers use local variables for most of their work. Global variables should be saved for data that truly needs sharing across your entire program. This approach leads to code that’s easier to understand, test, and maintain.

Final Programming Tips

- Start with local variables: Always try local first, then global only if needed

- Use descriptive names: `user_age` is better than `age` or `a`

- Group related variables: Keep similar data together for organization

- Avoid global when possible: Pass data through function parameters instead

- Use constants for fixed values: `PI = 3.14159` instead of magic numbers

Variable scope might feel confusing at first, but with practice, it becomes natural. You’ll start thinking about where your variables live and how long they need to exist. This mindset will make you a much more effective Python programmer.

Practice with the examples in this guide. Try modifying the code and see what happens. The best way to learn programming is by doing, not just reading. Each mistake teaches you something new about how Python works.

Interactive Python Variable Playground

Practice Python variable scope concepts with our interactive code playground. Try the examples below or write your own code to experiment with global and local variables.

Coding Challenges

Challenge 1: Create a global variable called ‘score’ with value 0. Write a function that increases the score by 10 each time it’s called.

Challenge 2: Create two functions with local variables that have the same name but different values. Print both values.

Challenge 3: Write a function that uses both global and local variables in the same calculation.

Common Python Variable Patterns and Best Practices

Understanding these common patterns will help you write cleaner, more maintainable Python code. These examples show real-world scenarios where variable scope matters.

Pattern 1: Configuration Variables

# Global configuration - good use of global variables

DEBUG_MODE = True

MAX_CONNECTIONS = 100

DEFAULT_TIMEOUT = 30

def connect_to_server():

if DEBUG_MODE:

print("Debug mode is enabled")

# Use configuration variables

timeout = DEFAULT_TIMEOUT

print(f"Connecting with timeout: {timeout}s")

def check_connections():

current_connections = 50 # Local variable

if current_connections > MAX_CONNECTIONS:

print("Too many connections!")

else:

print(f"Connections OK: {current_connections}/{MAX_CONNECTIONS}")

connect_to_server()

check_connections()

Pattern 2: Counter Functions

# Using global variables for counters

page_views = 0

user_sessions = 0

def track_page_view():

global page_views

page_views += 1

print(f"Page views: {page_views}")

def start_user_session():

global user_sessions

user_sessions += 1

session_id = f"session_{user_sessions}" # Local variable

print(f"Started {session_id}")

return session_id

# Test the tracking functions

track_page_view()

track_page_view()

start_user_session()

start_user_session()

Pattern 3: Avoiding Global Variables with Return Values

# Better approach: avoid global variables when possible

def calculate_total(items):

total = 0 # Local variable

tax_rate = 0.08 # Local variable

for item in items:

total += item

final_total = total * (1 + tax_rate)

return final_total

def format_currency(amount):

formatted = f"${amount:.2f}" # Local variable

return formatted

# Clean function calls without global variables

shopping_cart = [19.99, 24.50, 15.00]

cart_total = calculate_total(shopping_cart)

display_total = format_currency(cart_total)

print(f"Total: {display_total}")

Variable Scope Best Practices Summary

- Prefer local variables: Use function parameters and return values instead of global variables when possible

- Use global for configuration: Settings, constants, and application-wide state work well as globals

- Keep functions pure: Functions that don’t modify global state are easier to test and debug

- Use meaningful names: Clear variable names prevent confusion between global and local variables

- Group related globals: Keep configuration variables together at the top of your file

- Document global usage: Add comments when functions modify global variables

Troubleshooting Common Variable Scope Errors

Learn to identify and fix the most common Python variable scope errors. These examples show real problems programmers face and how to solve them.

Error 1: UnboundLocalError

# Problem code that causes UnboundLocalError

counter = 10

def increment():

counter = counter + 1 # ERROR!

return counter

# Solution: Use global keyword

def increment_fixed():

global counter

counter = counter + 1

return counter

# Alternative solution: Use parameters

def increment_better(current_value):

return current_value + 1

# Usage

# increment() # This would cause UnboundLocalError

result = increment_fixed()

print(f"Fixed result: {result}")

new_value = increment_better(counter)

print(f"Better approach: {new_value}")

Error 2: Accidental Variable Shadowing

# Problem: Accidentally shadowing built-in functions

list = [1, 2, 3] # Bad! Shadows built-in list()

def process_data():

str = "hello" # Bad! Shadows built-in str()

print = "debug" # Bad! Shadows built-in print()

# Solution: Use descriptive variable names

data_list = [1, 2, 3] # Good!

user_input = "hello" # Good!

debug_message = "debug" # Good!

def process_data_fixed():

user_string = "hello"

debug_info = "processing data"

print(f"{debug_info}: {user_string}") # print() still works!

process_data_fixed()

Error 3: Loop Variable Confusion

# Problem: Loop variable persists after loop

functions = []

# This creates a common bug

for i in range(3):

functions.append(lambda: print(f"Function {i}"))

# All functions print "Function 2" because i = 2 after loop

print("Problematic output:")

for func in functions:

func()

# Solution: Use default parameters or local scope

functions_fixed = []

for i in range(3):

functions_fixed.append(lambda x=i: print(f"Function {x}"))

print("\nFixed output:")

for func in functions_fixed:

func()

Leave a Reply