Parameter Passing Techniques in Python: A Complete Guide

Python Parameter Passing Techniques

Learning how to pass data to Python functions is super important. Think of it like giving instructions to a friend. You need to tell them exactly what information they need to do their job properly.

Python function parameters are the building blocks of good programming. They make your code reusable and flexible. When you master parameter passing techniques, you write better programs.

This complete guide covers everything about Python function arguments. We start with basic concepts and move to advanced techniques. By the end, you will understand all parameter types in Python programming.

Python developers use these parameter passing methods every day. Learning them helps you write cleaner code and solve complex problems easily.

What Are Function Parameters?

Function parameters are placeholders for data in Python functions. Think of them as empty containers waiting for information. When you create a function, you define these containers. When you call the function, you provide the actual data.

Python function arguments are the real values you pass to functions. The difference between parameters and arguments confuses many beginners. Parameters exist in the function definition. Arguments are what you actually send to the function when calling it.

Understanding this difference helps you write better Python code. It also makes debugging easier when things go wrong. Professional Python developers always know this distinction.

Quick Reference Guide:

Parameters: Empty placeholders in function definitions

Arguments: Actual values passed when calling functions

Function call: The action of using a function with specific data

Function definition: Where you create the function and set up parameters

def greet(name): # 'name' is a parameter

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

greet("Alice") # "Alice" is an argument

In this Python function example, name is the parameter. The parameter appears in the function definition line. When we call greet("Alice"), the string “Alice” becomes the argument. This argument fills the name parameter slot.

Notice how the function uses the parameter name inside its body. The parameter acts like a Python variable that holds the argument value. This makes functions flexible and reusable with different data.

Python function parameters follow specific naming rules. They should be descriptive and follow snake_case convention. Good parameter names make your code self-documenting and easier to understand.

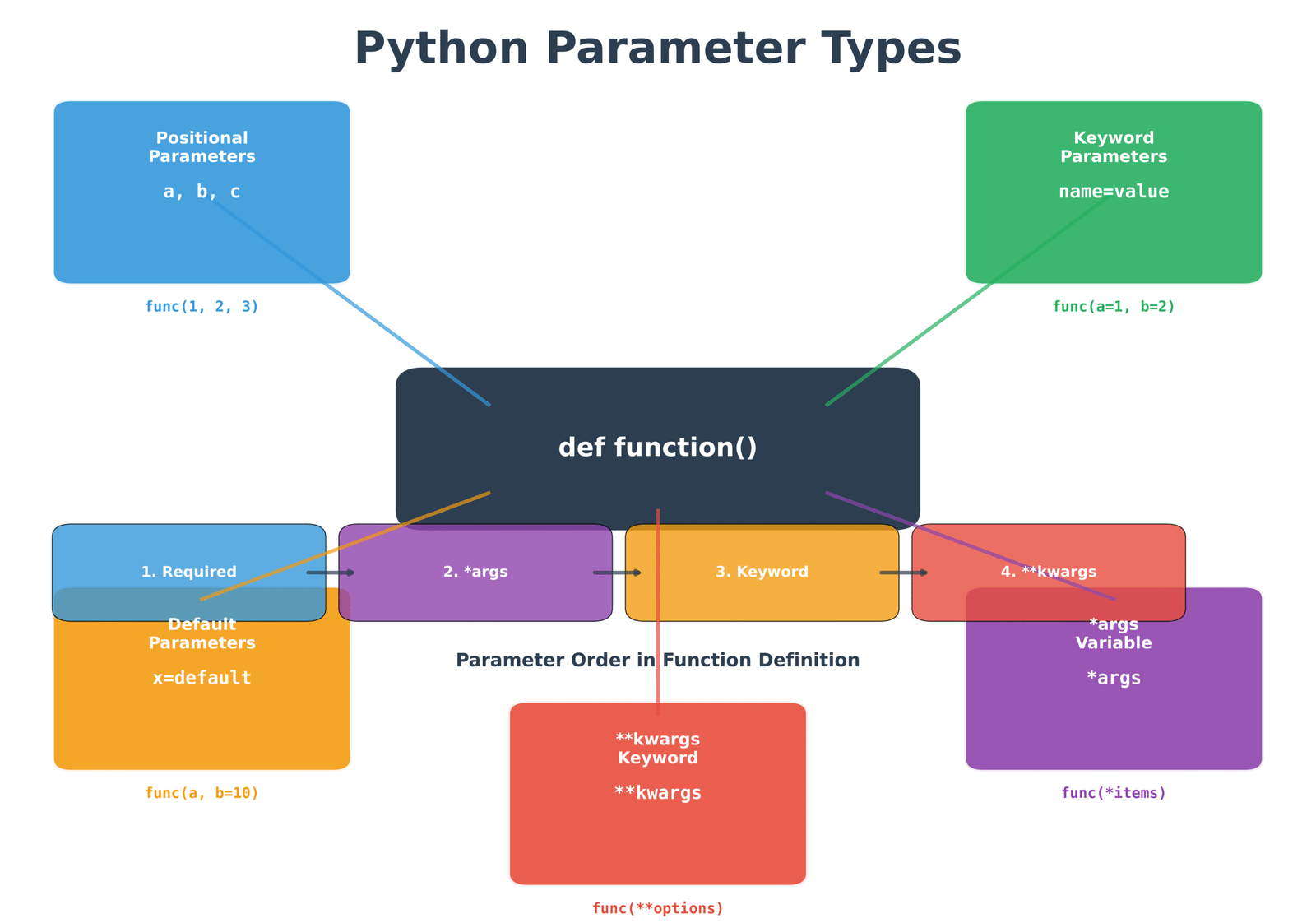

Basic Parameter Types

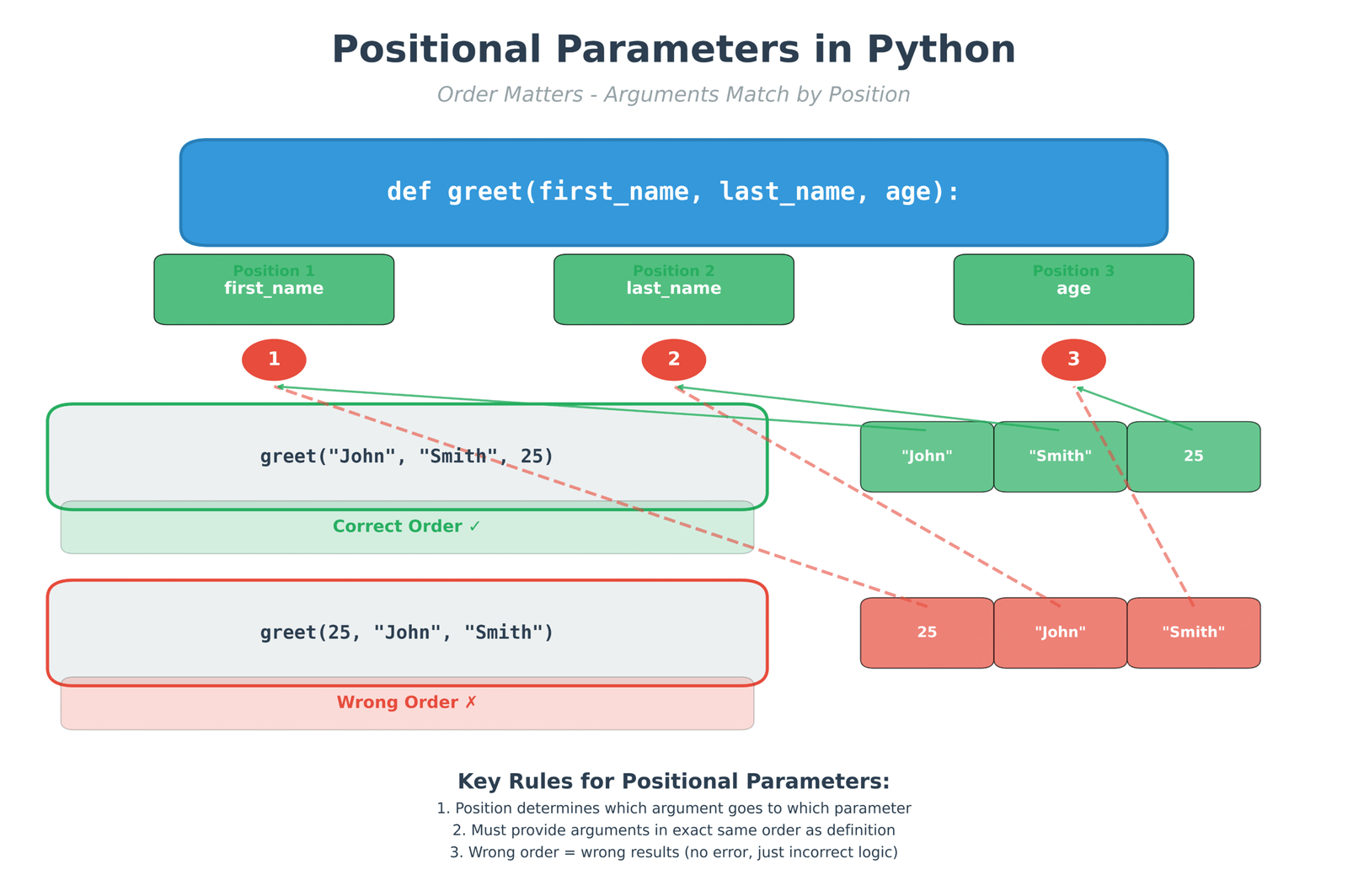

1. Positional Parameters in Python

Positional parameters are the most basic type of Python function parameters. They are also called positional arguments when you pass values to them. The position and order matter completely in positional parameter passing.

When you define positional parameters, Python expects arguments in the exact same order. The first argument goes to the first parameter. The second argument goes to the second parameter. This continues for all parameters in your function definition.

Most Python functions use positional parameters because they are simple and direct. New programmers learn positional parameters first. They form the foundation of Python function argument passing.

def introduce(first_name, last_name, age):

print(f"Hi, I'm {first_name} {last_name}")

print(f"I am {age} years old")

# Order matters here - first_name, last_name, age

introduce("John", "Smith", 25)

# Wrong order causes problems

introduce(25, "Smith", "John")

The first function call works perfectly because we follow the correct parameter order. The second call shows what happens when you mix up positional arguments. Python does not check if the data types make sense. It just assigns values based on position.

Positional parameter passing requires careful attention to argument order. One mistake can break your entire function logic. This is why many Python developers prefer other parameter types for complex functions.

- Position determines which argument goes to which parameter

- You must provide arguments in the exact definition order

- Missing arguments cause TypeError exceptions

- Extra arguments also cause TypeError exceptions

- Wrong order leads to logical errors, not syntax errors

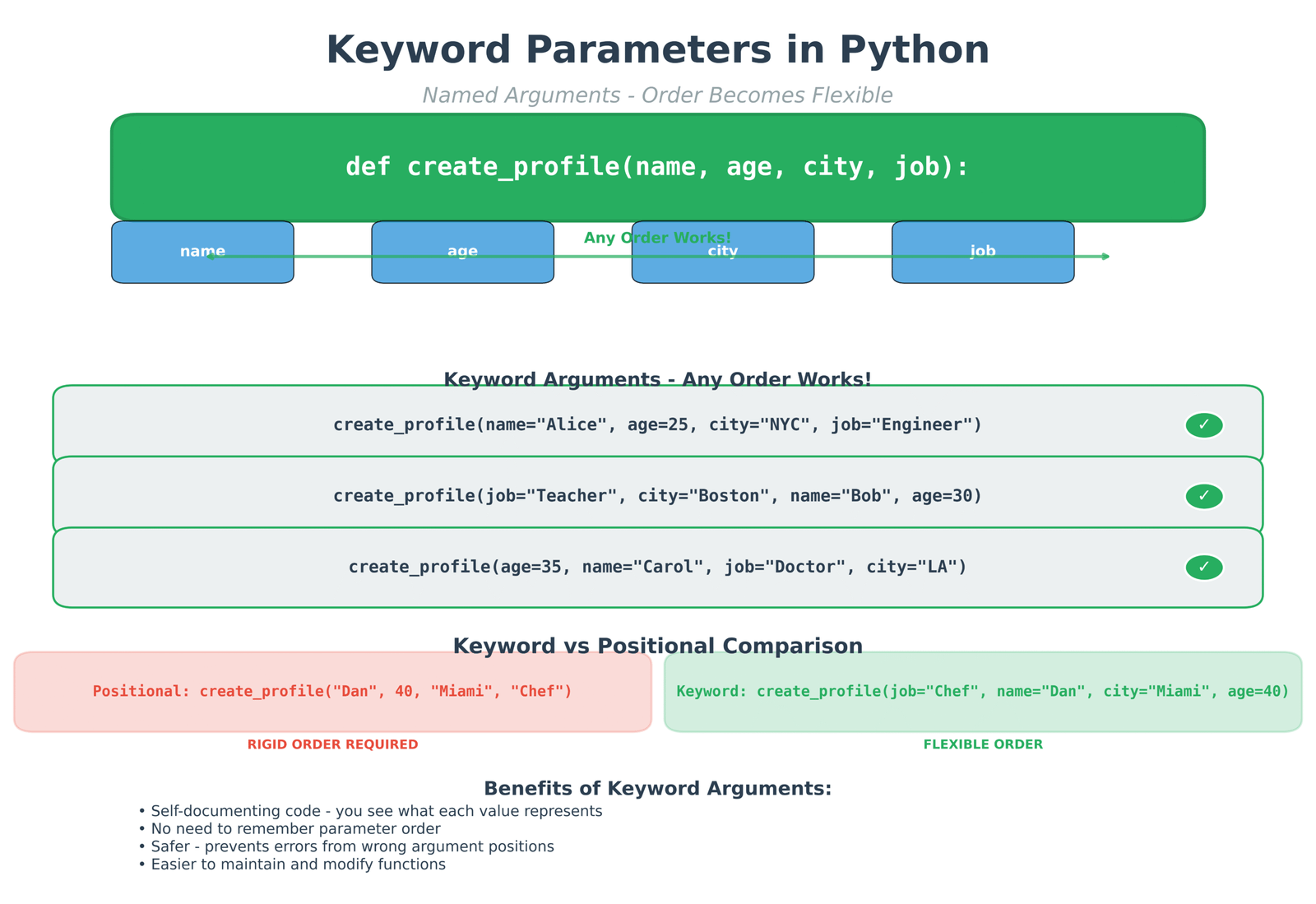

2. Keyword Parameters and Named Arguments

Keyword parameters let you specify which value goes to which parameter by name. This is also called named argument passing in Python. With keyword arguments, the order becomes completely flexible and optional.

Python keyword arguments make function calls much more readable. Instead of remembering parameter positions, you use parameter names directly. This prevents common mistakes that happen with positional arguments.

Professional Python developers prefer keyword arguments for functions with many parameters. They make code self-documenting and easier to maintain. Python function arguments become clearer when you use descriptive names.

def make_sandwich(bread, filling, sauce):

print(f"Making a {bread} sandwich with {filling} and {sauce}")

# Using keywords - order doesn't matter

make_sandwich(filling="chicken", sauce="mayo", bread="white")

make_sandwich(bread="whole wheat", filling="turkey", sauce="mustard")

# Mix positional and keyword arguments

make_sandwich("rye", filling="ham", sauce="mustard")

The first two function calls use only keyword arguments. Notice how the parameter order changes but the result stays correct. The third call mixes positional and keyword arguments, showing Python’s flexibility.

Keyword argument passing has important rules. All positional arguments must come before keyword arguments. You cannot specify the same parameter twice. These rules prevent confusion and ambiguity in function calls.

Benefits of Keyword Arguments:

Readability: Code becomes self-documenting and clear

Flexibility: Parameter order becomes irrelevant

Safety: Reduces errors from wrong argument positions

Maintenance: Adding new parameters becomes easier

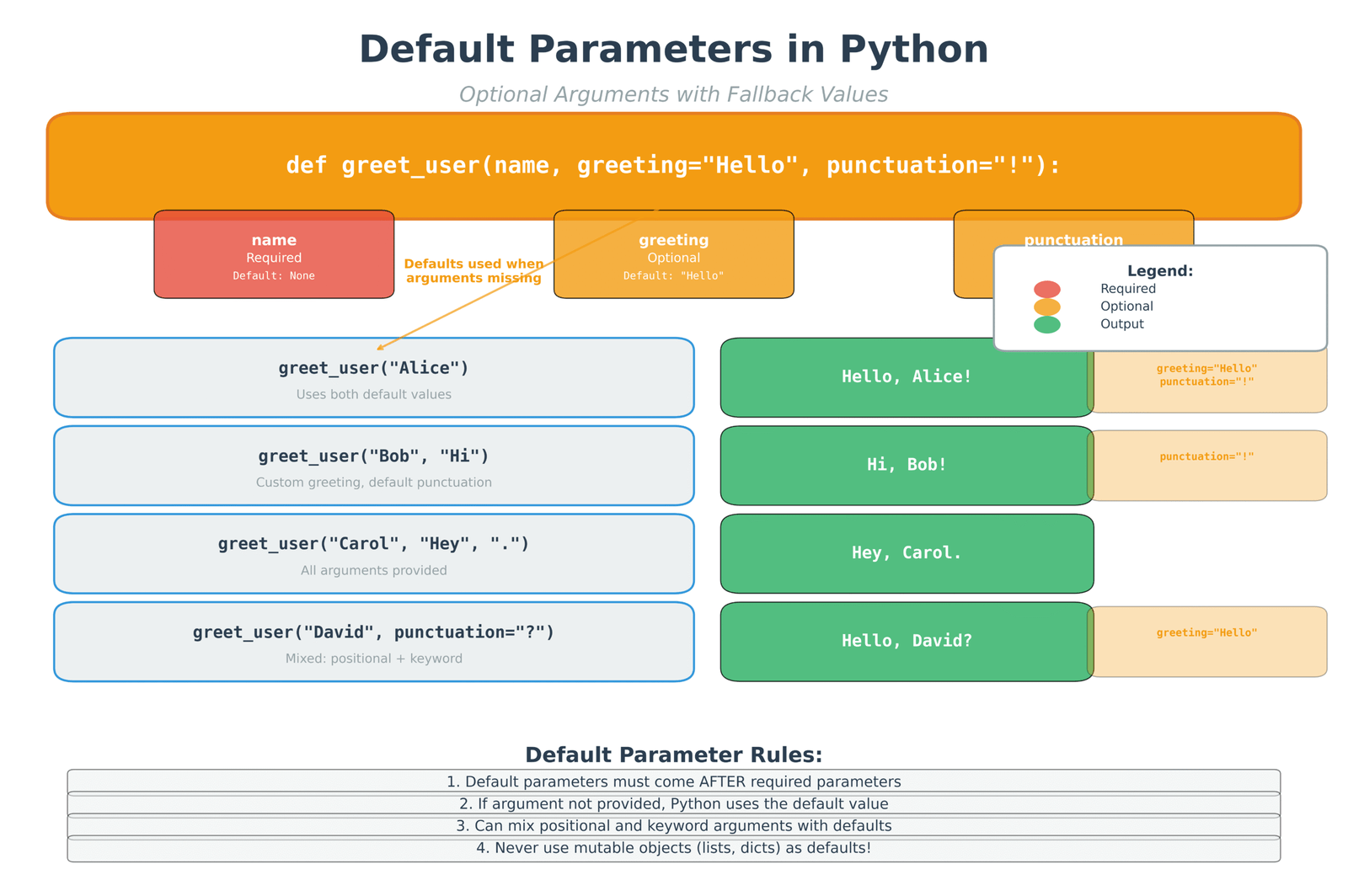

3. Default Parameters and Optional Arguments

Default parameters provide fallback values when callers do not specify arguments. They are also called optional parameters because providing arguments becomes optional. Default parameter values make Python functions more flexible and user-friendly.

When you define default parameters, you assign values directly in the function definition. Python uses these default values automatically when arguments are missing. This prevents TypeError exceptions that would occur with required parameters.

Default parameter techniques are common in Python programming. They let you create functions that work with minimal input but allow customization when needed. Function parameters and return values become much more powerful with default values.

def greet_person(name, greeting="Hello", punctuation="!"):

print(f"{greeting}, {name}{punctuation}")

# Using all defaults except name

greet_person("Alice")

# Customizing greeting only

greet_person("Bob", "Hi there")

# Customizing everything

greet_person("Charlie", "Hey", ".")

# Using keyword arguments with defaults

greet_person("Diana", punctuation="?")

The first call uses default values for both greeting and punctuation. The second call overrides the greeting but keeps the default punctuation. The third call provides all arguments. The fourth call shows how keyword arguments work with default parameters.

Default parameter placement has strict rules in Python. All default parameters must come after required parameters. You cannot have a required parameter after a default parameter. This rule prevents ambiguity in function calls.

Default Parameter Best Practices:

Common Values: Use defaults for the most frequently used values

Immutable Types: Only use immutable objects as default values

Documentation: Document what default values represent

Order: Place required parameters before optional ones

Testing: Test functions with and without default arguments

Advanced Parameter Techniques in Python

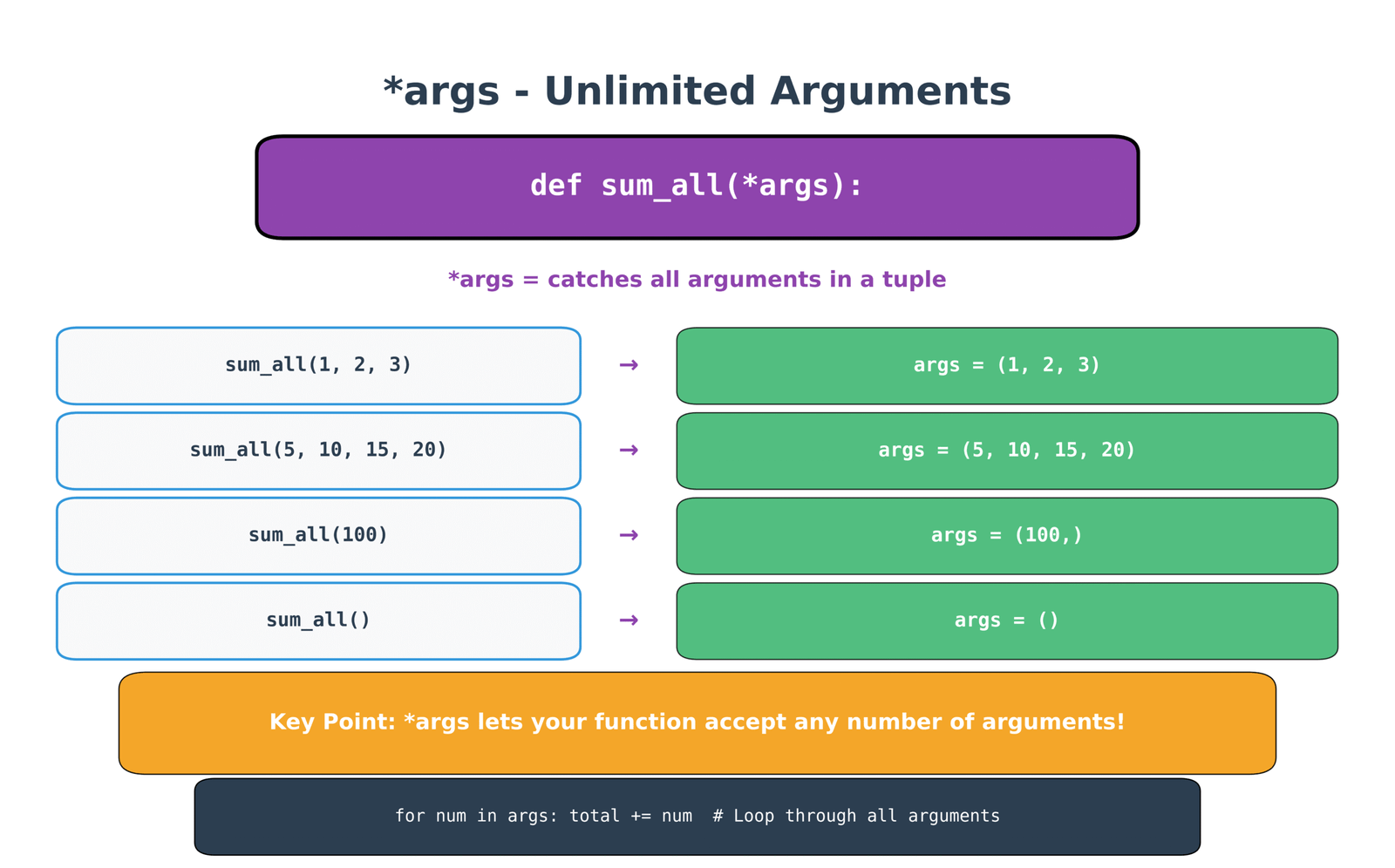

Variable-Length Arguments (*args) – Arbitrary Positional Parameters

Python *args syntax allows functions to accept unlimited positional arguments. This advanced parameter technique solves the problem of not knowing how many arguments users will provide. Variable-length arguments make functions extremely flexible and powerful.

The asterisk (*) before the parameter name tells Python to collect all extra positional arguments. These arguments get packed into a tuple automatically. Inside your function, you can iterate through this tuple or access individual elements.

Python *args parameter passing is common in built-in functions like print() and max(). Professional developers use *args when building flexible APIs and utility functions. Understanding *args helps you write more versatile Python code.

def add_numbers(*numbers):

"""Add any number of numeric arguments."""

if not numbers:

return 0

total = 0

for num in numbers:

total += num

return total

# Can pass any number of arguments

print("Adding 3 numbers:", add_numbers(1, 2, 3))

print("Adding 5 numbers:", add_numbers(10, 20, 30, 40, 50))

print("Adding 1 number:", add_numbers(5))

print("Adding no numbers:", add_numbers())

# *args creates a tuple

def show_args_type(*args):

print(f"Type of args: {type(args)}")

print(f"Contents: {args}")

show_args_type("apple", "banana", "cherry")

The add_numbers function works with any number of arguments, including zero arguments. Python automatically converts the arguments into a tuple. The show_args_type function demonstrates that *args creates a tuple containing all passed arguments.

Variable argument functions handle edge cases gracefully. Always check if the *args tuple is empty when necessary. This prevents errors and makes your functions more robust in real-world applications.

Understanding *args Behavior:

Packing: Python packs multiple arguments into a single tuple

Iteration: You can loop through args like any tuple

Indexing: Access specific arguments with args[0], args[1], etc.

Length: Use len(args) to count how many arguments were passed

Unpacking: Use *args to pass the tuple to other functions

def demonstrate_args_features(*args):

print(f"Number of arguments: {len(args)}")

if args:

print(f"First argument: {args[0]}")

print(f"Last argument: {args[-1]}")

print("All arguments:")

for i, arg in enumerate(args):

print(f" Position {i}: {arg}")

demonstrate_args_features("hello", 42, True, [1, 2, 3])

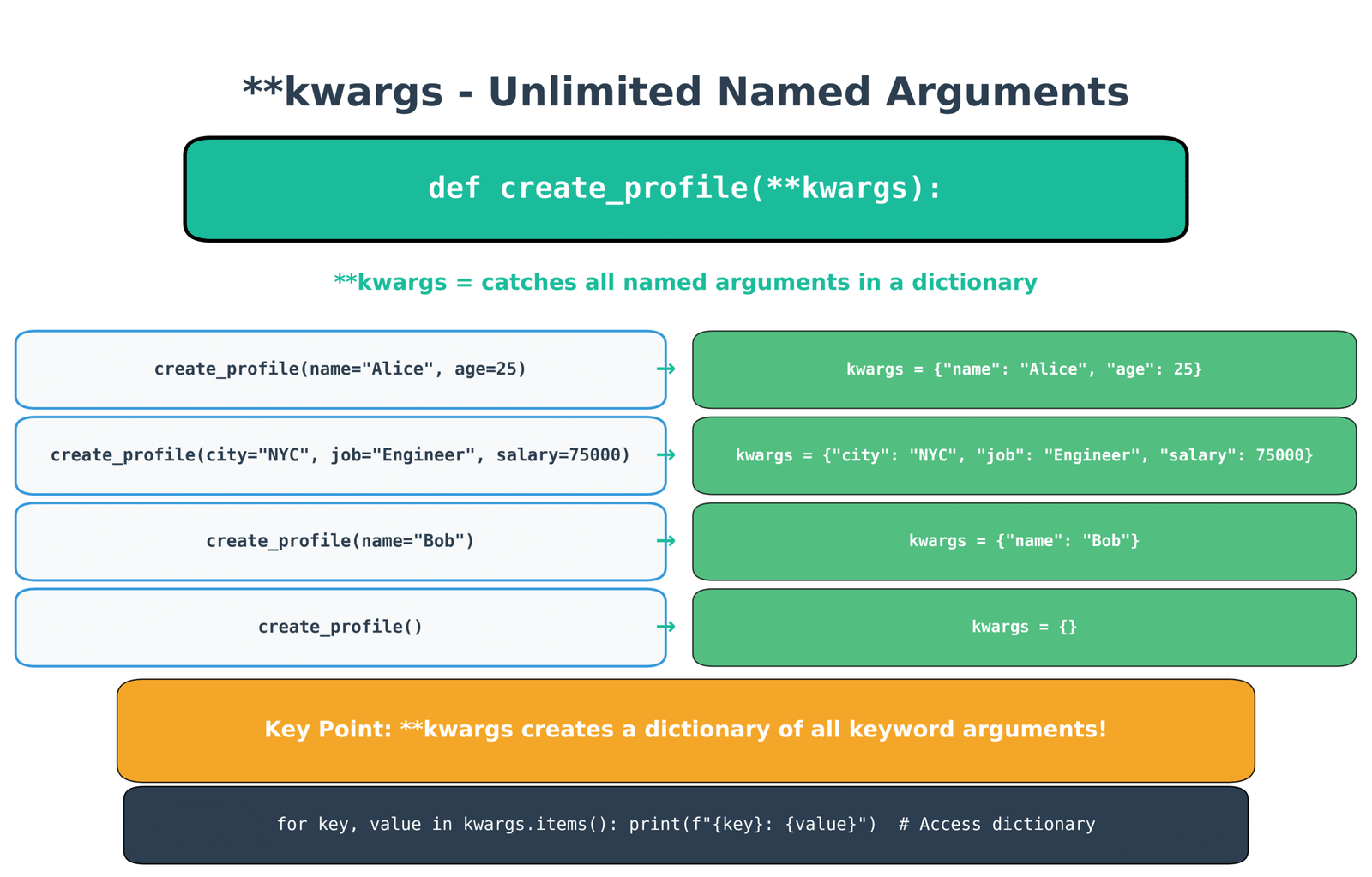

Keyword Variable Arguments (**kwargs) – Arbitrary Named Parameters

Python **kwargs syntax captures unlimited keyword arguments in a dictionary. This advanced parameter technique complements *args by handling named arguments dynamically. Double asterisk (**) tells Python to collect extra keyword arguments into a dictionary.

The **kwargs parameter creates a dictionary where keys are argument names and values are the passed data. This powerful technique allows functions to accept any number of named parameters without defining them explicitly in the function signature.

Professional Python developers use **kwargs for configuration functions, API wrappers, and flexible interfaces. Understanding **kwargs and how it works with dictionaries makes your functions incredibly adaptable to changing requirements.

def create_profile(name, **details):

"""Create a user profile with flexible additional information."""

print(f"Profile for: {name}")

print(f"Additional details: {len(details)} items")

for key, value in details.items():

print(f" {key}: {value}")

# Access specific keys if they exist

if 'age' in details:

print(f"Age category: {'Adult' if details['age'] >= 18 else 'Minor'}")

create_profile("Alice", age=25, city="New York", job="Engineer", hobby="Photography")

print()

create_profile("Bob", age=16, school="High School", grade=11)

print()

# **kwargs creates a dictionary

def show_kwargs_type(**kwargs):

print(f"Type of kwargs: {type(kwargs)}")

print(f"Dictionary contents: {kwargs}")

show_kwargs_type(name="Charlie", score=95, passed=True)

The create_profile function handles different types of user information flexibly. It processes any keyword arguments users provide while still accessing specific keys when needed. The show_kwargs_type function demonstrates that **kwargs creates a regular Python dictionary.

Keyword variable arguments enable powerful design patterns in Python. You can pass configuration options, handle optional settings, and build extensible APIs. Python dictionaries created by **kwargs are mutable and can be modified inside functions.

**kwargs Dictionary Operations:

Key Access: Use kwargs[‘key’] or kwargs.get(‘key’) to access values

Key Checking: Use ‘key’ in kwargs to check if a key exists

Iteration: Loop through kwargs.items() for key-value pairs

Modification: Add, update, or remove dictionary entries

Passing Along: Use **kwargs to forward arguments to other functions

def process_data(data, **options):

"""Process data with configurable options."""

print(f"Processing: {data}")

# Handle different processing options

if options.get('uppercase', False):

data = data.upper()

print(f"Converted to uppercase: {data}")

if options.get('reverse', False):

data = data[::-1]

print(f"Reversed: {data}")

max_length = options.get('max_length')

if max_length and len(data) > max_length:

data = data[:max_length] + "..."

print(f"Truncated to {max_length} chars: {data}")

return data

# Different configuration combinations

result1 = process_data("hello world", uppercase=True, reverse=True)

print(f"Final result 1: {result1}")

print()

result2 = process_data("this is a long sentence", max_length=10, uppercase=True)

print(f"Final result 2: {result2}")

Combining All Parameter Types

You can use all these parameter types together, but you must follow a specific order:

| Order | Parameter Type | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regular positional | name, age |

| 2 | *args | *hobbies |

| 3 | Keyword with defaults | city=”Unknown” |

| 4 | **kwargs | **extra_info |

def complete_function(name, age, *hobbies, city="Unknown", **extra_info):

print(f"Name: {name}")

print(f"Age: {age}")

print(f"City: {city}")

if hobbies:

print("Hobbies:", ", ".join(hobbies))

for key, value in extra_info.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}")

# Using the function

complete_function("Alice", 25, "reading", "swimming",

city="Boston", job="Teacher", pet="cat")

How Python Handles Different Data Types in Parameter Passing

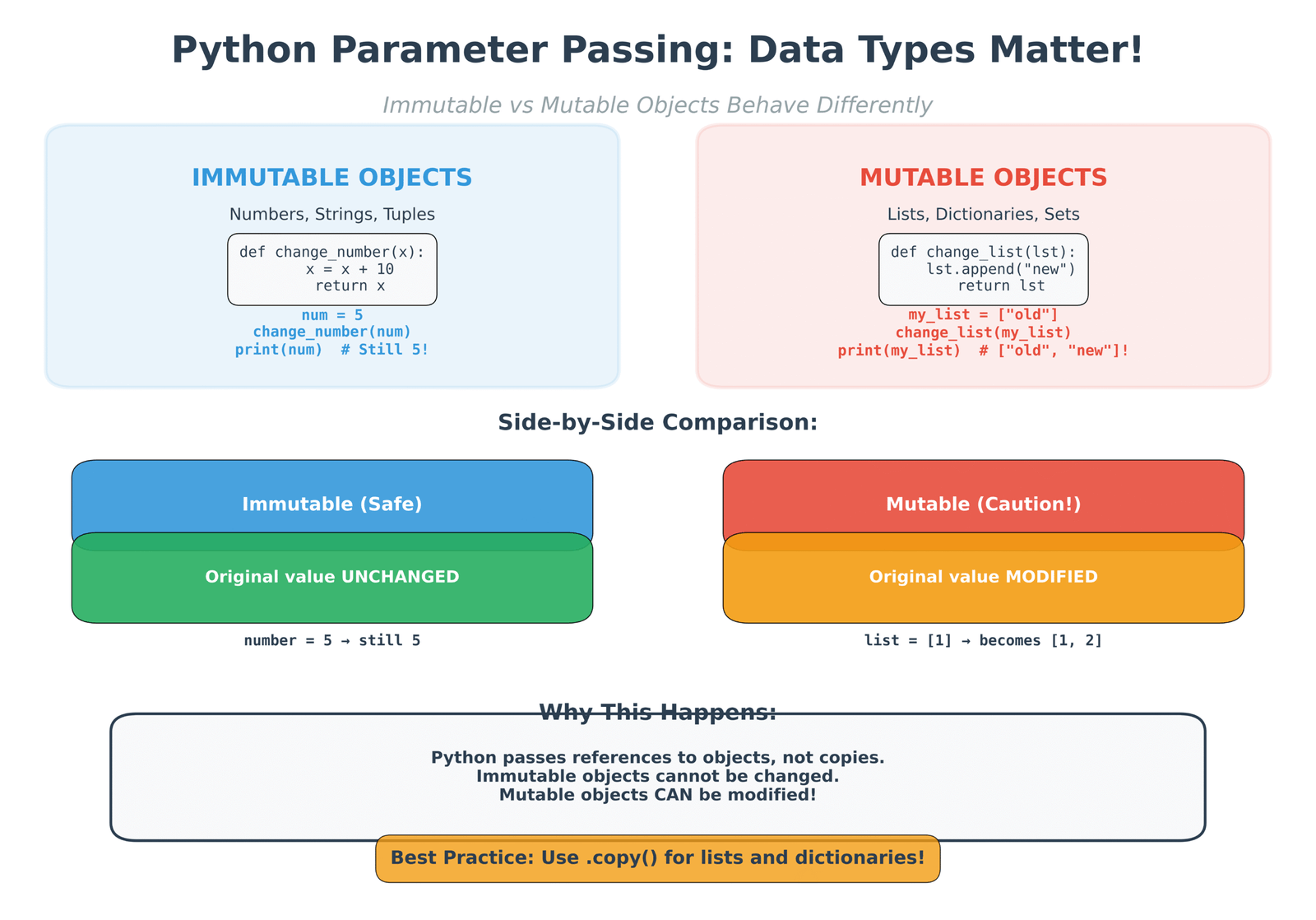

Understanding Python object passing behavior is crucial for writing correct programs. Python handles mutable and immutable objects differently when passing them as function arguments. This difference affects how your functions interact with data.

Python uses a concept called “pass by object reference” for all parameter passing. This means Python passes references to objects, not copies of the objects themselves. However, what happens next depends on whether the object is mutable or immutable.

Professional Python developers must understand this distinction to avoid common bugs. Many beginners struggle with unexpected behavior when their functions modify or preserve original data. Learning these concepts early prevents hours of debugging later.

Immutable Objects – Numbers, Strings, and Tuples

Immutable objects cannot be changed after creation. When you pass immutable objects to functions, any “changes” create new objects instead of modifying originals. Numbers, strings, tuples, and frozensets are immutable in Python.

Function parameters that receive immutable objects behave like local copies. You can modify the parameter variable inside the function, but this never affects the original value outside. This behavior prevents accidental data corruption and makes functions more predictable.

def try_to_change_number(x):

print(f"Inside function, x starts as: {x}")

x = x + 10

print(f"Inside function, x is now: {x}")

number = 5

print(f"Before function call: {number}")

try_to_change_number(number)

print(f"After function call: {number}")

Notice that the original number variable stays unchanged. This is because numbers are immutable in Python.

Mutable Objects – Lists, Dictionaries, and Sets

Mutable objects can be modified after creation. When you pass mutable objects to Python functions, the function receives a reference to the actual object. Any modifications inside the function directly affect the original object outside the function.

Lists, dictionaries, sets, and custom objects are mutable in Python. This behavior enables powerful programming patterns but can cause unexpected side effects. Understanding mutable object passing prevents common programming errors and data corruption issues.

Many Python developers get surprised by mutable object behavior initially. The key is remembering that functions work with the same object, not a copy. This concept becomes important when building larger applications with shared data structures.

def modify_data_structures(my_list, my_dict, my_set):

"""Demonstrate mutable object modification in functions."""

print("=== Before modifications ===")

print(f"List: {my_list}")

print(f"Dict: {my_dict}")

print(f"Set: {my_set}")

# Modify the list

my_list.append("new_item")

my_list[0] = "changed"

# Modify the dictionary

my_dict["new_key"] = "new_value"

my_dict["existing"] = "updated"

# Modify the set

my_set.add("extra")

my_set.discard("original")

print("\n=== After modifications ===")

print(f"List: {my_list}")

print(f"Dict: {my_dict}")

print(f"Set: {my_set}")

# Create mutable objects

shopping_list = ["apples", "bread"]

user_data = {"name": "Alice", "existing": "old_value"}

tags = {"original", "important"}

print("OUTSIDE FUNCTION - Before call:")

print(f"List: {shopping_list}")

print(f"Dict: {user_data}")

print(f"Set: {tags}")

modify_data_structures(shopping_list, user_data, tags)

print("\nOUTSIDE FUNCTION - After call:")

print(f"List: {shopping_list}")

print(f"Dict: {user_data}")

print(f"Set: {tags}")

All three mutable objects were modified permanently. The changes persist outside the function because Python passes references to the same objects. This demonstrates why understanding object mutability is critical for Python programming.

When you need to preserve original data, create copies before passing to functions. Python provides several copying methods for different scenarios. Shallow copies work for simple cases, while deep copies handle nested mutable objects.

def safe_list_operations(original_list):

"""Demonstrate safe operations that preserve original data."""

# Create a copy to avoid modifying the original

working_list = original_list.copy() # or list(original_list)

print(f"Original list: {original_list}")

print(f"Working copy: {working_list}")

# Modify only the copy

working_list.append("added_safely")

working_list[0] = "modified_copy"

print(f"After modifications:")

print(f"Original list: {original_list}")

print(f"Working copy: {working_list}")

return working_list

# Test with copying

my_data = ["item1", "item2", "item3"]

result = safe_list_operations(my_data)

print(f"\nFinal original: {my_data}")

print(f"Function result: {result}")

- Always document if your function modifies input parameters

- Use .copy() for lists and dictionaries when preservation is needed

- Consider returning new objects instead of modifying inputs

- Use copy.deepcopy() for nested mutable structures

- Test functions with both approaches to verify behavior

Understanding Object Identity

Python has a built-in function called id() that shows the unique identity of an object. This helps you understand what is happening with your data.

def check_identity(data):

print(f"Inside function, id of data: {id(data)}")

# Test with a list (mutable)

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

print(f"Outside function, id of my_list: {id(my_list)}")

check_identity(my_list)

print()

# Test with a number (immutable)

my_number = 42

print(f"Outside function, id of my_number: {id(my_number)}")

check_identity(my_number)

Both the list and number have the same id inside and outside the function. This proves that Python passes references to objects, not copies.

Advanced Function Concepts

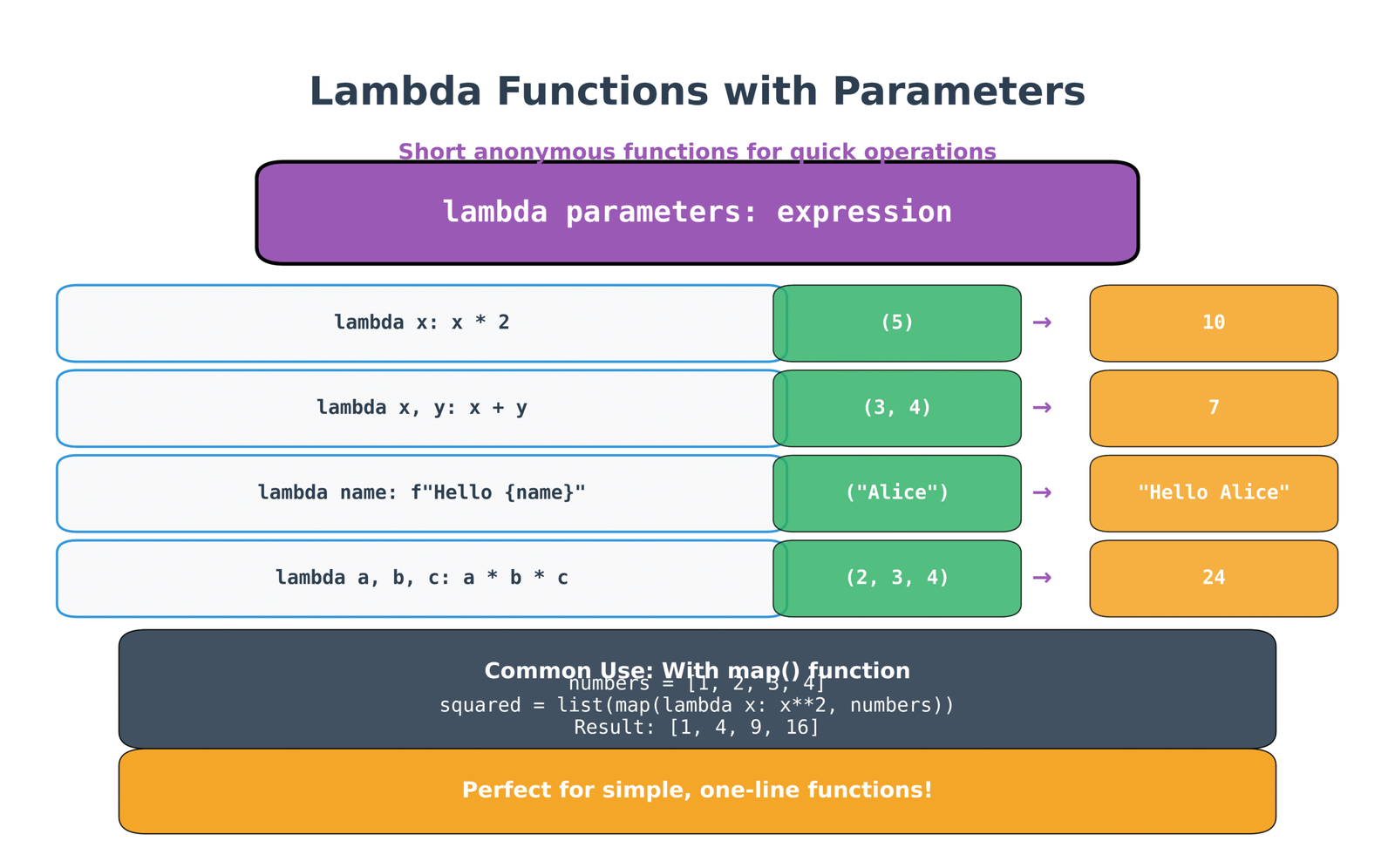

Lambda Functions with Parameters

Lambda functions are small, anonymous functions. They are useful for quick operations that you do not want to define as full functions.

# Regular function

def multiply(x, y):

return x * y

# Same thing as a lambda

multiply_lambda = lambda x, y: x * y

print("Regular function:", multiply(4, 5))

print("Lambda function:", multiply_lambda(4, 5))

# Using lambda with built-in functions

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

squared = list(map(lambda x: x**2, numbers))

print("Squared numbers:", squared)

Function Annotations

You can add hints to your functions to show what types of parameters they expect and what they return. This makes your code more readable.

def calculate_area(length: float, width: float) -> float:

"""Calculate the area of a rectangle."""

return length * width

def greet_user(name: str, times: int = 1) -> None:

"""Greet a user a specified number of times."""

for i in range(times):

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

# Using the annotated functions

area = calculate_area(5.5, 3.2)

print(f"Area: {area}")

greet_user("Alice", 2)

The annotations do not change how the function works. They are just helpful hints for other programmers (and yourself) reading the code later.

Interactive Exercises

Write a function that can perform basic math operations. It should take two numbers and an operation (add, subtract, multiply, divide).

Write a function that takes a student name, grade, and any number of subjects. It should print all the information nicely.

Interactive Quiz

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake 1: Mutable Default Arguments

Never use mutable objects like lists as default parameter values. This creates unexpected behavior.

# WRONG - Don't do this!

def add_item_wrong(item, my_list=[]):

my_list.append(item)

return my_list

# Each call uses the same list!

print(add_item_wrong("apple"))

print(add_item_wrong("banana")) # Still has "apple"!

# CORRECT - Do this instead

def add_item_correct(item, my_list=None):

if my_list is None:

my_list = []

my_list.append(item)

return my_list

print(add_item_correct("orange"))

print(add_item_correct("grape")) # Fresh list each time

Mistake 2: Forgetting Return Values

Functions that process data should usually return the result, not just print it.

# Less useful - only prints

def calculate_tax_print(amount, tax_rate):

tax = amount * tax_rate

print(f"Tax: ${tax}")

# More useful - returns the value

def calculate_tax_return(amount, tax_rate):

tax = amount * tax_rate

return tax

# Now you can use the result in other calculations

price = 100

tax = calculate_tax_return(price, 0.08)

total = price + tax

print(f"Total with tax: ${total}")

Real-World Examples

Example 1: Data Processing Function

Here is how you might process student grades in a real application:

def process_student_grades(name, *grades, **options):

"""Process student grades with various options."""

if not grades:

return "No grades provided"

# Calculate basic statistics

total = sum(grades)

average = total / len(grades)

highest = max(grades)

lowest = min(grades)

# Check options

show_details = options.get('show_details', False)

passing_grade = options.get('passing_grade', 60)

# Determine if passing

is_passing = average >= passing_grade

status = "PASSING" if is_passing else "NEEDS IMPROVEMENT"

# Build result

result = f"{name}: Average = {average:.1f}% ({status})"

if show_details:

result += f"\n Grades: {grades}"

result += f"\n Highest: {highest}%, Lowest: {lowest}%"

result += f"\n Total points: {total}"

return result

# Using the function

print(process_student_grades("Alice", 85, 92, 78, 88))

print()

print(process_student_grades("Bob", 45, 67, 52,

show_details=True, passing_grade=65))

Example 2: Configuration Function

Functions with flexible arguments are great for configuration:

def setup_database_connection(host, port=5432, **config):

"""Setup database connection with flexible configuration."""

print(f"Connecting to database at {host}:{port}")

# Handle common configuration options

if 'username' in config:

print(f"Username: {config['username']}")

if 'database' in config:

print(f"Database: {config['database']}")

if 'ssl' in config:

ssl_status = "enabled" if config['ssl'] else "disabled"

print(f"SSL: {ssl_status}")

# Handle any other custom options

other_options = {k: v for k, v in config.items()

if k not in ['username', 'database', 'ssl']}

if other_options:

print("Additional options:")

for key, value in other_options.items():

print(f" {key}: {value}")

# Different ways to use the function

setup_database_connection("localhost", username="admin", database="myapp")

print()

setup_database_connection("remote-server", 3306,

username="user", ssl=True,

timeout=30, pool_size=10)

Python Function Parameter Best Practices and Coding Standards

Following Python parameter passing best practices makes your code professional and maintainable. These guidelines come from years of Python development experience and community standards. Professional Python developers follow these patterns consistently.

Good parameter design reduces bugs, improves code readability, and makes functions easier to use. When you follow these practices, other developers can understand and use your functions quickly. This becomes crucial when working on team projects or open-source Python libraries.

Essential Parameter Design Rules:

- Descriptive Names: Use clear parameter names that explain data purpose and type

- Logical Order: Place required parameters first, optional parameters last

- Smart Defaults: Choose default values that work for 80% of use cases

- Clear Documentation: Document parameter types, purposes, and examples

- Immutable Defaults: Never use mutable objects as default parameter values

- Type Annotations: Add type hints to make function interfaces crystal clear

- Validation: Check parameter values and raise meaningful error messages

- Consistency: Follow the same patterns across your entire codebase

Good Parameter Naming

Choose names that make your function self-documenting. Follow Python naming conventions for consistency.

# Bad - unclear names

def calc(x, y, z):

return x + (y * z)

# Good - clear names

def calculate_total_price(base_price, tax_rate, quantity):

return base_price + (tax_rate * quantity)

# Even better - with type hints and documentation

def calculate_total_price(base_price: float,

tax_rate: float,

quantity: int) -> float:

"""

Calculate total price including tax.

Args:

base_price: The base price per item

tax_rate: Tax rate as a decimal (e.g., 0.08 for 8%)

quantity: Number of items

Returns:

Total price including tax

"""

return base_price + (tax_rate * quantity)

Frequently Asked Questions

Additional Resources

Learn More About Python Functions

Summary

You have learned everything about passing parameters to Python functions. Here are the key points to remember:

- Parameters vs Arguments: Parameters are placeholders in function definitions, arguments are the actual values you pass

- Positional Parameters: Order matters, arguments must be in the same order as parameters

- Keyword Parameters: Order does not matter, you specify which argument goes to which parameter

- Default Parameters: Provide fallback values when arguments are not given

- *args: Accept any number of positional arguments

- **kwargs: Accept any number of keyword arguments

- Mutable vs Immutable: Functions can modify mutable objects (lists, dicts) but not immutable ones (numbers, strings)

Practice these concepts with your own functions. Start simple and gradually add more complex parameter patterns as you get comfortable. Remember, the goal is to make your functions flexible and easy to use.

For more advanced Python topics, check out our guide on developing object detection models to see these concepts in action in real projects.

Leave a Reply