Python Tuples: Immutability as a Design Contract

Python Tuples: Immutability as a Design Contract

When you first learn about tuples in Python, someone probably told you: “A tuple is just a list you cannot change.” That explanation is technically correct. But it misses the entire point.

Python did not add tuples to restrict you. It added them to let you make promises. A tuple tells everyone reading your code: this data is stable. Count on it. It will not change behind your back.

Think of it this way. When you sign a contract, you are making a promise. You are saying “I will do this thing, and you can rely on it.” A tuple is the same kind of promise, written in code.

Why Python Needs Both Lists and Tuples

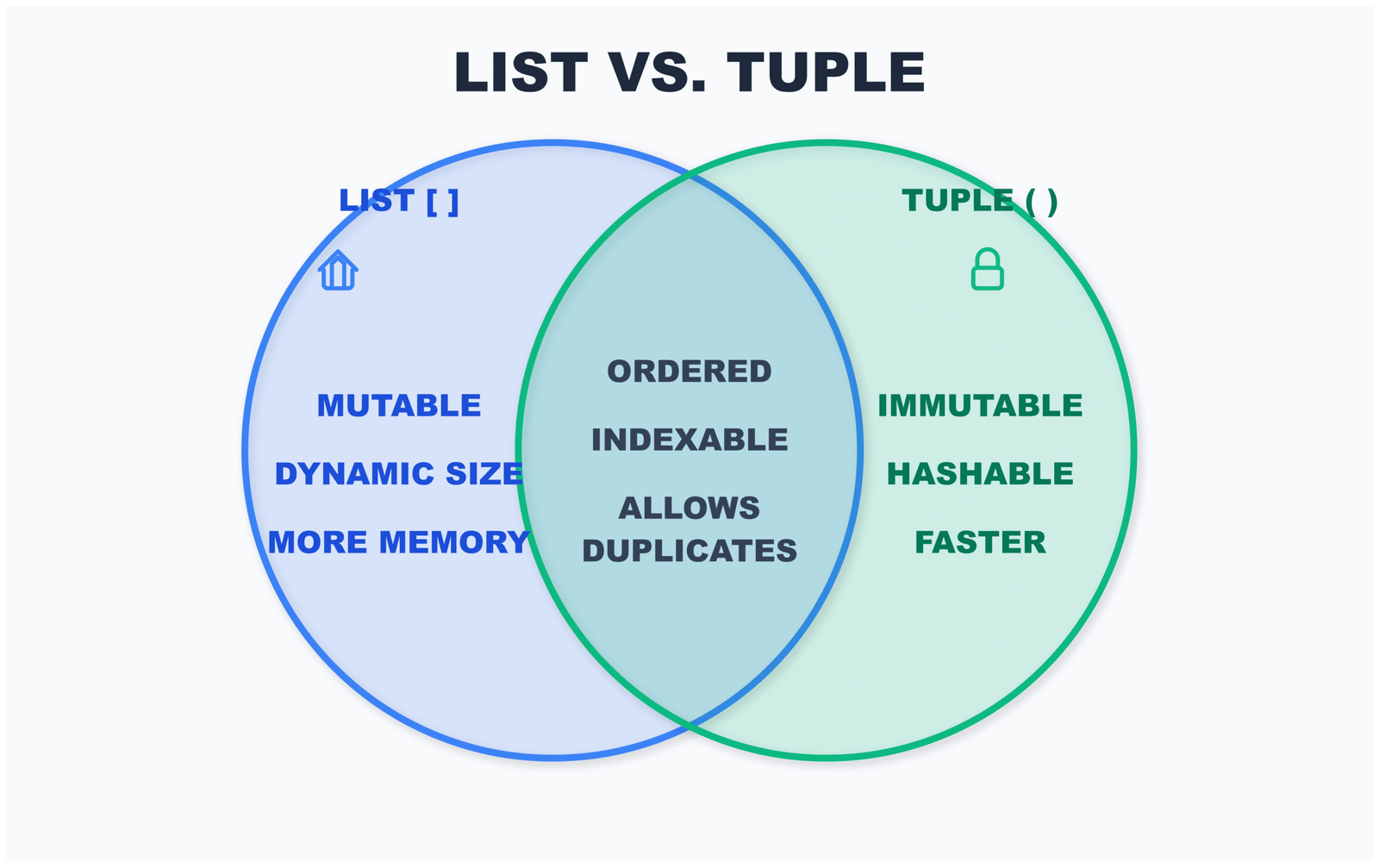

If lists can do everything tuples can do, why have tuples at all? The answer lies in communication, not just functionality.

When you use a list, you are saying: “This collection might change. Items might get added. Items might get removed. The order might shift.” When you use a tuple, you are saying the opposite: “This is final. What you see is what you get.”

This distinction helps other programmers understand your code faster. It also helps you avoid mistakes. Let me show you what I mean.

Try This: List vs Tuple Behavior

Click the buttons to see how lists and tuples behave differently:

How Tuples Save Memory and Improve Performance

Tuples are not just about communication. They also give you real technical benefits. Because tuples cannot change, Python can optimize how it stores them in memory.

Fixed Size Means Less Overhead

When you create a list, Python has to prepare for the possibility that you will add more items later. It allocates extra space. This is called over-allocation. It makes appending items faster, but it wastes memory if you never actually add anything.

Tuples do not have this problem. Python knows exactly how much space a tuple needs, and it allocates only that amount. Nothing extra. Nothing wasted.

import sys

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

my_tuple = (1, 2, 3)

print(f"List size: {sys.getsizeof(my_list)} bytes")

print(f"Tuple size: {sys.getsizeof(my_tuple)} bytes")

# Output:

# List size: 88 bytes

# Tuple size: 64 bytes

The difference might seem small here. But when you create thousands or millions of these collections, the savings add up quickly.

Why Immutability Enables Dictionary Keys and Set Membership

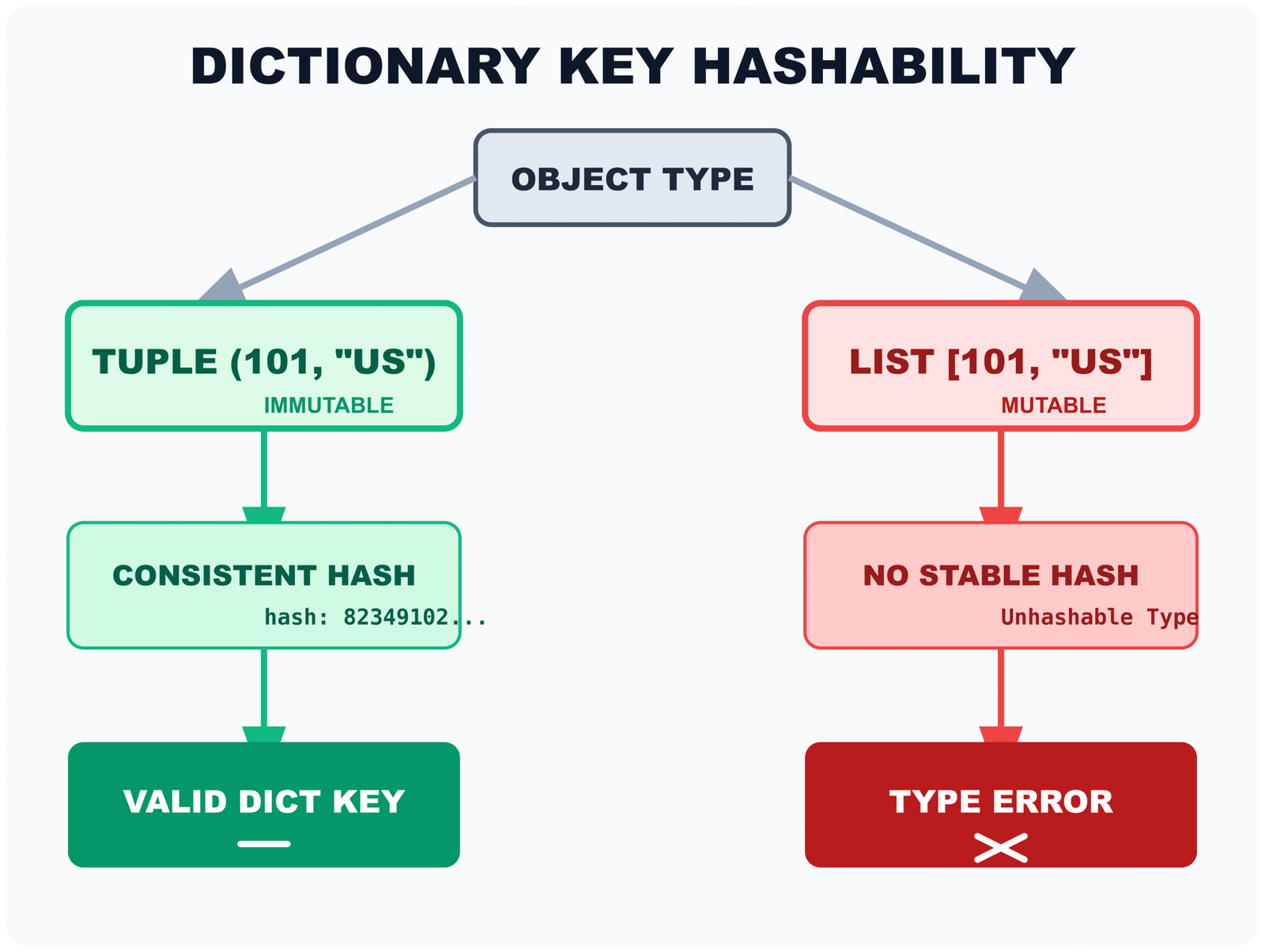

Here is something you cannot do with lists: use them as dictionary keys. Try it, and Python will throw an error.

# This fails

cache = {}

key = [1, 2, 3]

cache[key] = "some value"

# TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

Why does this fail? Because dictionaries rely on hashing. When you use something as a dictionary key, Python calculates a hash value for it. That hash value helps Python find the key quickly.

But if the key can change, its hash value would change too. The dictionary would break. Python would not be able to find your data anymore.

Tuples solve this problem. Because they cannot change, their hash values stay stable. This makes them perfect for dictionary keys.

# This works perfectly

cache = {}

cache_key = (user_id, region, version)

cache[cache_key] = result

# Real world example: coordinate system

grid = {}

position = (10, 25) # x, y coordinates

grid[position] = "treasure"

# Later, you can retrieve it

treasure_location = grid[(10, 25)]

This pattern appears everywhere in real systems. Web frameworks use tuples to cache route handlers. Database libraries use them to cache query results. Game engines use them to store grid positions.

The Immutable Container Trap: What Tuples Actually Protect

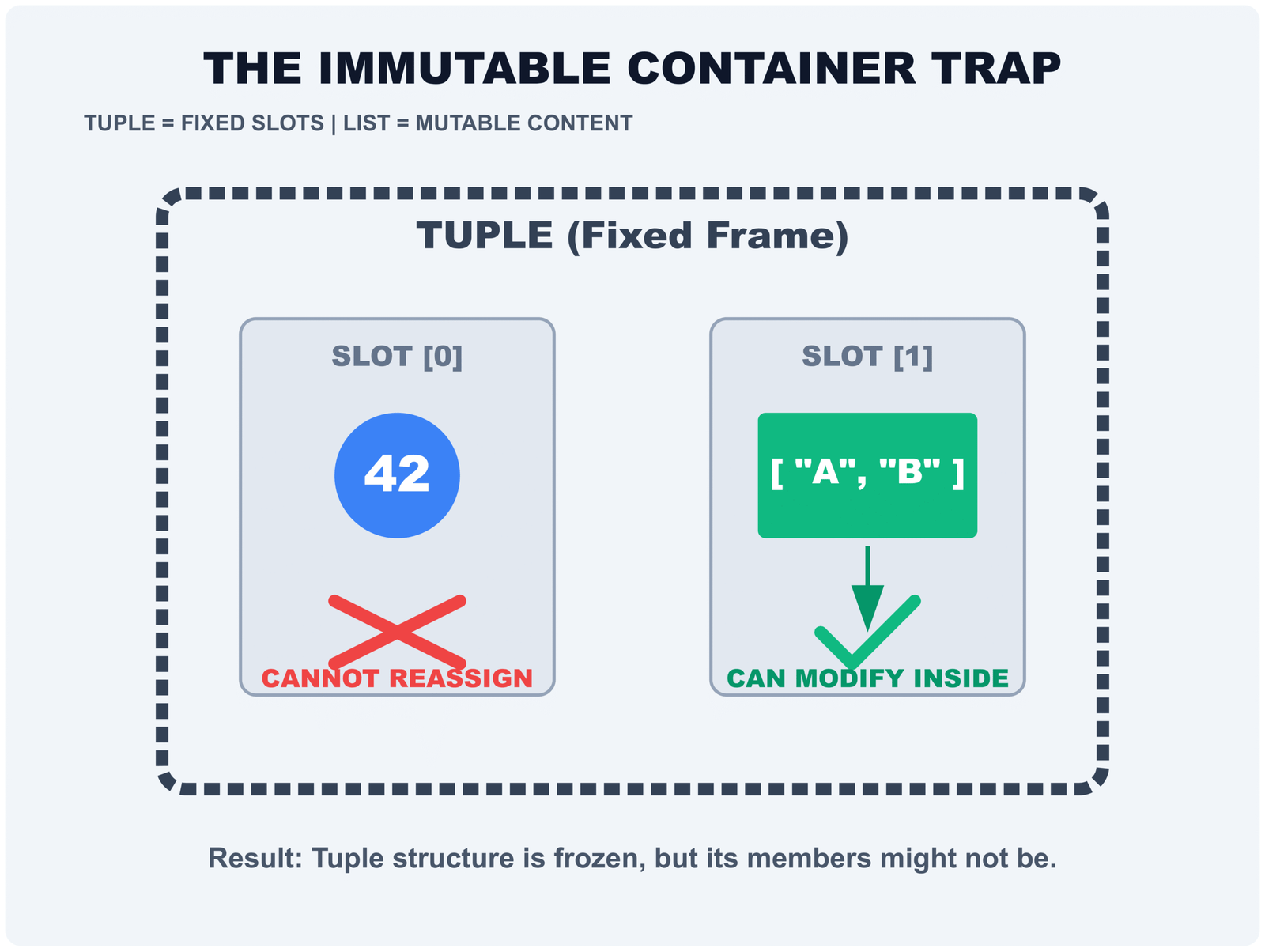

Here is where things get interesting. Tuples are immutable, but that does not mean everything inside them is immutable. This confuses a lot of people.

Let me show you what I mean:

data = (1, [2, 3])

print(data) # (1, [2, 3])

# You cannot replace the list

data[1] = [4, 5] # TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

# But you CAN modify the list itself

data[1].append(4)

print(data) # (1, [2, 3, 4])

Understand the Difference

So what does this mean for you? If you want tuples to act as true contracts, only put immutable values inside them. Use numbers, strings, other tuples, or frozen sets. Avoid lists, dictionaries, or custom objects that can change.

Using Tuples as Data Records Instead of Mini Objects

One of the best uses for tuples is representing fixed data records. These are collections where the position of each item has meaning.

Real World Examples Where Order Matters

# Geographic coordinates: always (latitude, longitude)

location = (37.7749, -122.4194)

# RGB color values: always (red, green, blue)

color = (255, 128, 0)

# Date ranges: always (start, end)

quarter = (date(2024, 1, 1), date(2024, 3, 31))

# Screen dimensions: always (width, height)

resolution = (1920, 1080)

In each of these examples, swapping the order would break the meaning. A coordinate of (longitude, latitude) would point to the wrong place. An RGB value of (blue, green, red) would produce the wrong color.

Tuples protect you from these mistakes. If you tried to use a dictionary instead, someone could accidentally swap keys. If you used a list, someone might reorder the items. Tuples prevent both problems.

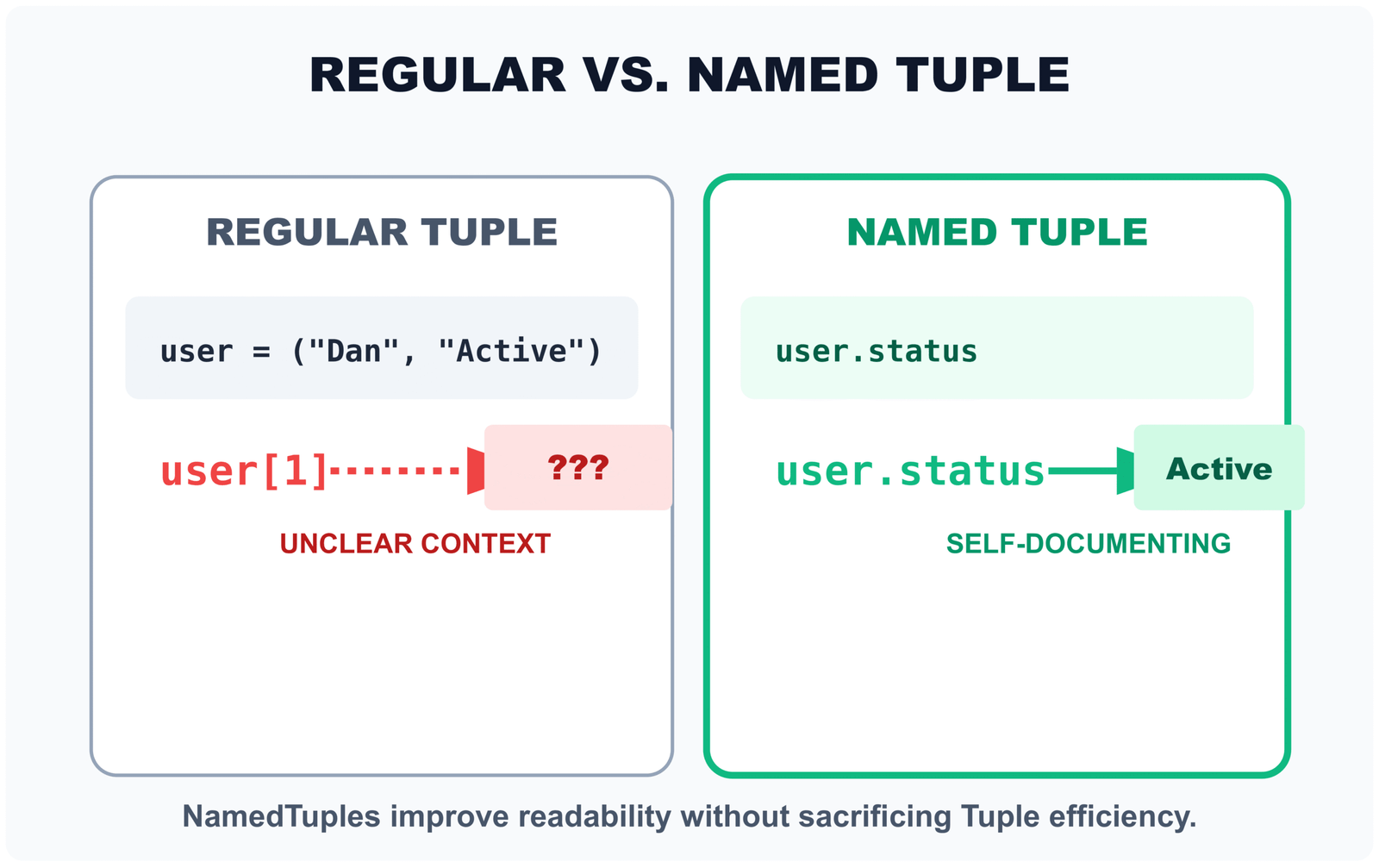

When Tuples Need Documentation: Named Tuples

Sometimes the meaning of a tuple is not obvious. What does (42, “active”, 1.5) represent? You would have to read documentation or trace through code to figure it out.

Python gives you a better option: named tuples. These are tuples that document themselves.

from collections import namedtuple

# Without namedtuple: unclear

user = (42, "active", 1.5)

status = user[1] # What is index 1?

# With namedtuple: self-documenting

User = namedtuple('User', ['id', 'status', 'rating'])

user = User(id=42, status="active", rating=1.5)

status = user.status # Clear and readable

Named tuples give you the best of both worlds. You get the efficiency and immutability of tuples, plus the readability of objects with named attributes.

How Tuples Communicate Intent at Function Boundaries

One place where tuples shine is at the edges of functions. When you return a tuple from a function, you are making a promise: this output is stable and complete.

Return Values That Signal Stability

def parse_http_header(raw_data: bytes) -> tuple[int, str, dict]:

"""

Parse HTTP response header.

Returns:

tuple: (status_code, status_message, headers)

This return type tells callers:

- You get exactly three values

- They come in a specific order

- They will not change after being returned

"""

status_code = 200

status_message = "OK"

headers = {"Content-Type": "application/json"}

return (status_code, status_message, headers)

# Caller knows exactly what to expect

code, message, headers = parse_http_header(data)

Compare this to returning a list. A list says “here are some items, maybe in this order, maybe not.” A tuple says “here are exactly these items, in exactly this order, and they are final.”

Function Parameters That Prevent Mutation

When you accept a tuple as a function parameter, you signal to callers: I will not modify this data.

def calculate_distance(point_a: tuple[float, float],

point_b: tuple[float, float]) -> float:

"""

Calculate distance between two points.

Args:

point_a: (x, y) coordinates - will not be modified

point_b: (x, y) coordinates - will not be modified

The tuple type in the signature is a promise:

Your original coordinates are safe.

"""

x1, y1 = point_a

x2, y2 = point_b

return ((x2 - x1) ** 2 + (y2 - y1) ** 2) ** 0.5

# Caller can trust their data is safe

my_location = (10.0, 20.0)

target = (30.0, 40.0)

distance = calculate_distance(my_location, target)

# my_location is guaranteed unchanged

Practical Benefits Throughout the Development Lifecycle

The contract that tuples provide affects more than just how your code runs. It affects how you develop, debug, and maintain your code.

Debugging Becomes Easier With Fewer State Changes

When you debug code with mutable data structures, you have to track where and when changes happen. Did this list get modified in function A or function B? Who added this extra item? Why did the order change?

With tuples, those questions disappear. If you create a tuple with three items, it will have three items everywhere in your code. No surprises. No hidden mutations.

# With lists: mutation could happen anywhere

def process_data(items):

result = []

for item in items:

transformed = transform(item)

# Did transform() modify items? You have to check.

result.append(transformed)

return result

# With tuples: no mutation possible

def process_data(items: tuple) -> tuple:

result = []

for item in items:

transformed = transform(item)

# items cannot change. You know this for certain.

result.append(transformed)

return tuple(result)

Thread Safety Gets a Head Start

When multiple parts of your program run at the same time, shared mutable data creates problems. One thread might change data while another thread reads it. The results can be unpredictable and hard to debug.

Tuples reduce this risk. If data cannot change, threads can share it safely. You still need to think about concurrency. Tuples do not magically solve all threading problems. But they eliminate one major source of bugs.

from threading import Thread

# Risky: shared mutable state

shared_data = [1, 2, 3]

def worker_thread():

# Another thread might modify shared_data right now

total = sum(shared_data) # Race condition possible

# Safer: shared immutable state

shared_data = (1, 2, 3)

def worker_thread():

# No other thread can modify shared_data

total = sum(shared_data) # Safe to read

Common Mistakes When Using Tuples

Even though tuples are simple, people make predictable mistakes with them. Knowing these pitfalls helps you avoid them.

Mistake One: Using Tuples Where Mutation Is Expected

def collect_user_scores(num_users):

scores = () # Starting with empty tuple

for i in range(num_users):

score = get_user_score(i)

scores = scores + (score,) # Creating new tuple each time

return scores

This code works, but it creates a new tuple on every iteration. That is wasteful. Use a list when building a collection, then convert to a tuple if needed.

def collect_user_scores(num_users):

scores = [] # Using list for accumulation

for i in range(num_users):

score = get_user_score(i)

scores.append(score)

return tuple(scores) # Convert to tuple when done

Build your collection with a list, then freeze it as a tuple when you are done. This is both clearer and faster.

Mistake Two: Returning Magic Index Tuples

def get_user_info(user_id):

# What do these positions mean?

return (42, "john_doe", "john@example.com", "premium", 2024)

# Caller has to remember or guess

user_data = get_user_info(123)

email = user_data[2] # Is this the email? Or the username?

When tuple positions have no obvious meaning, readers have to memorize what each index represents. This leads to bugs.

from collections import namedtuple

UserInfo = namedtuple('UserInfo',

['id', 'username', 'email', 'plan', 'year_joined'])

def get_user_info(user_id):

return UserInfo(

id=42,

username="john_doe",

email="john@example.com",

plan="premium",

year_joined=2024

)

# Clear and self-documenting

user_data = get_user_info(123)

email = user_data.email # Obvious what this is

Named tuples make your code self-documenting. Six months from now, you will thank yourself.

Mistake Three: Packing Unrelated Data Together

# Mixing unrelated concepts

user_data = (username, last_login, server_ip, cpu_usage)

This tuple mixes user information with server metrics. They are unrelated concepts. Putting them in one tuple makes code harder to understand.

# Separate related data

user_session = (username, last_login)

server_status = (server_ip, cpu_usage)

Group related data together. Keep unrelated data separate. Your code will be easier to understand and modify.

Decision Framework: When Should You Choose a Tuple

How do you decide between a tuple, a list, or another data structure? Here is a practical checklist.

- Will this data change after creation? If no, consider a tuple.

- Does the position of items have specific meaning? If yes, a tuple works well.

- Are you passing data across function boundaries? Tuples signal stability.

- Do you need to use this as a dictionary key? You need a tuple.

- Are you representing a fixed record or coordinate? Tuples are ideal.

Here is another way to think about it:

| Scenario | Use Tuple When | Use List When |

|---|---|---|

| Storing coordinates | Data represents a fixed point | Data represents a path that grows |

| Function return values | Returning fixed set of results | Returning variable collection |

| Configuration data | Settings should not change | Settings are dynamic |

| Database query results | Row represents fixed schema | Collecting multiple rows |

| Dictionary keys | Always use tuple if needed | Cannot use list as key |

Test Your Understanding

Which data structure would you choose for these scenarios?

Real World Pattern: Tuples in Production Systems

Let me show you how tuples appear in actual production code. These are not toy examples. These are patterns you will see in real software.

Web Framework Route Caching

class Router:

def __init__(self):

self.route_cache = {}

def get_handler(self, method: str, path: str, version: str):

# Tuple as cache key

cache_key = (method, path, version)

if cache_key in self.route_cache:

return self.route_cache[cache_key]

handler = self._find_handler(method, path, version)

self.route_cache[cache_key] = handler

return handler

# Why this works:

# 1. Cache keys need to be hashable - tuples work

# 2. Route info should not change - tuples enforce this

# 3. Order matters - (GET, "/users", "v1") != ("/users", GET, "v1")

Database Query Result Rows

def fetch_users(database):

"""

Each row is a tuple representing fixed schema.

"""

query = "SELECT id, name, email FROM users"

cursor = database.execute(query)

# Each row comes back as a tuple

for row in cursor:

user_id, name, email = row

process_user(user_id, name, email)

# Why databases use tuples:

# 1. Schema is fixed - columns do not change mid-query

# 2. Order matches SQL SELECT clause

# 3. Immutable rows prevent accidental corruption

Game Development Grid Systems

class GameGrid:

def __init__(self):

self.entities = {} # Maps position to entity

self.terrain = {} # Maps position to terrain type

def place_entity(self, x: int, y: int, entity):

position = (x, y)

if position in self.entities:

raise ValueError(f"Position {position} occupied")

self.entities[position] = entity

def get_neighbors(self, x: int, y: int) -> list[tuple[int, int]]:

# Return neighboring positions

return [

(x-1, y), # Left

(x+1, y), # Right

(x, y-1), # Up

(x, y+1), # Down

]

# Why games use tuples for positions:

# 1. Positions are fixed points in space

# 2. Can be used as dictionary keys for fast lookups

# 3. Clear that positions should not change accidentally

Tuples as Engineering Signals in Code Reviews

When you write code, you communicate with two audiences. The first is the computer. The second is other programmers, including your future self.

Tuples send a clear signal to both audiences. To the computer, they say “optimize this for immutability.” To other programmers, they say “do not try to change this.”

# This function signature tells reviewers a lot

def calculate_metrics(

data_points: tuple[float, ...],

thresholds: tuple[float, float, float]

) -> tuple[float, float]:

"""

What the tuple types communicate:

data_points: tuple - I will not modify your input data

thresholds: Fixed set of exactly 3 values expected

return: tuple - Results are stable, exactly 2 values

"""

pass

Compare that to this version:

def calculate_metrics(data_points, thresholds):

"""

What this signature communicates:

Nothing clear. Might the function modify inputs?

How many thresholds? What gets returned?

Reviewers have to read implementation to know.

"""

pass

The first version reduces the mental effort needed to understand the code. That is valuable on any team.

Conclusion: Write Code That Makes Promises

Tuples are not just about preventing changes. They are about making your intentions clear. When you use a tuple, you tell everyone who reads your code: this data has a fixed structure. You can rely on it.

That promise has real benefits. It makes debugging easier because you eliminate a whole category of bugs. It makes code reviews faster because reviewers spend less time tracking mutations. It makes systems more reliable because shared data is safer.

The next time you reach for a list, pause. Ask yourself: will this data change? If the answer is no, consider using a tuple instead. Make that promise. Write that contract. Your code will be better for it.

- Tuples encode intent, not just functionality

- They reduce reasoning cost for everyone reading your code

- They make systems easier to trust and maintain

- Choose them when data should not change

Start small. Pick one place in your code where you used a list for data that never changes. Convert it to a tuple. See how it feels. Then do it again.

Over time, this habit will change how you think about data structures. You will start designing with immutability in mind. Your code will become clearer. Your bugs will decrease. And other developers will have an easier time understanding what you built.

That is what good engineering looks like. Not clever tricks. Not advanced techniques. Just clear communication through code. Tuples help you do exactly that.

External Resources

External Resources for Further Reference

Here are high-quality, reliable resources to deepen your understanding of Python tuples:

- Official Python Documentation – Data Structures section: https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/datastructures.html Authoritative reference with tuple basics and comparisons to lists.

- Real Python – Python’s tuple Data Type: A Deep Dive: https://realpython.com/python-tuple In-depth tutorial with examples, performance notes, and advanced uses.

- GeeksforGeeks – Python Tuples: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python/python-tuples Comprehensive overview with operations, methods, and code examples.

- Programiz – Python Tuple (With Examples): https://www.programiz.com/python-programming/tuple Beginner-friendly with clear explanations and interactive examples.

- W3Schools – Python Tuples: https://www.w3schools.com/python/python_tuples.asp Quick reference with simple examples and exercises.

- Real Python – Lists and Tuples Course: https://realpython.com/courses/lists-tuples-python Focused comparison of lists vs. tuples with practical manipulation techniques.

Quiz on Python Tuples

Python Tuples Mastery Quiz

Quiz Complete!

Great effort! Tuples are a fundamental part of Python’s data structure ecosystem.

FAQ Section: 6 Common Questions

What is the main difference between a list and a tuple in Python?

Lists are mutable (can be changed after creation), while tuples are immutable in structure (size and order are fixed). Tuples use less memory, are hashable (if contents are immutable), and signal that the data is intended to remain constant.

Are tuples completely immutable?

No. The tuple’s structure is immutable — you can’t add, remove, or reorder elements. However, if a tuple contains mutable objects (like lists or dictionaries), those inner objects can still be modified.

Why would I return a tuple from a function instead of individual values?

Returning a tuple packs multiple values together while guaranteeing the structure (number and order of returned items) won’t change accidentally. It also allows clean unpacking on the caller side.

When should I use a named tuple instead of a regular tuple?

Use a named tuple when you have more than 3 fields or when the code will be read/maintained by others. It provides readable attribute access (e.g., txn.amount) while keeping immutability and low overhead.

Can I use a tuple as a dictionary key?

Yes, but only if all elements inside the tuple are immutable (numbers, strings, or other immutable tuples). This is because tuples are hashable when their contents are immutable.

Is it inefficient to “modify” a tuple by creating a new one (e.g., via concatenation)?

Yes, if done frequently in a loop. The article advises using lists for data that truly needs to grow or change, and converting to a tuple only at the end if immutability is needed.

Leave a Reply