Check If a Tuple Is Sorted in Python — 5 Methods Explained

How to Check if a Python Tuple is Sorted: 5 Efficient Methods

Tuples and Sorted Checking: What Makes Them Different

Checking whether a tuple is sorted in Python follows the same logic as checking a list — compare consecutive elements pairwise — but there are a few practical differences worth understanding before writing code.

Tuples are immutable. You cannot sort them in place. Calling .sort() on a tuple raises an AttributeError because that method does not exist for tuples. sorted() works, but it returns a new list, not a tuple. This means any sort-based approach for checking order requires an extra conversion step and creates new objects in memory — which is unnecessary if all you need is a boolean answer.

t = (3, 1, 4, 1, 5) t.sort() # AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'sort' sorted(t) # Returns [1, 1, 3, 4, 5] — a list, not a tuple tuple(sorted(t)) # Returns (1, 1, 3, 4, 5) — correct type, but wasteful for just checking

The methods below check sorted order directly, without sorting. They all run in O(n) time with early exit — the check stops the moment it finds an out-of-order pair. If the tuple is already sorted (the common case for validation), the entire check is one sequential pass through the data.

Sorted Order: What You’re Actually Checking

There are two different definitions depending on whether you allow duplicate values:

- Non-decreasing — each element is less than or equal to the next.

(1, 2, 2, 3)qualifies. Use<=. - Strictly increasing — each element must be strictly less than the next.

(1, 2, 2, 3)does not qualify. Use<.

The same distinction applies in descending order: non-increasing (>=, duplicates allowed) versus strictly decreasing (>, no duplicates). The implementation only changes the comparison operator — the structure of every method below stays the same.

TypeError in Python 3. Tuples containing mixed types need a safe wrapper, which is covered in the edge cases section below.

Method 1: all() with zip() — Recommended for Most Cases

Time: O(n)Space: O(1)*

def is_sorted(t):

return all(x <= y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:]))

# Examples

is_sorted((1, 2, 3, 4, 5)) # True

is_sorted((1, 3, 2, 4)) # False

is_sorted((5, 5, 5)) # True — duplicates are fine with <=

is_sorted(()) # True — empty tuple

is_sorted((7,)) # True — single element

How it works

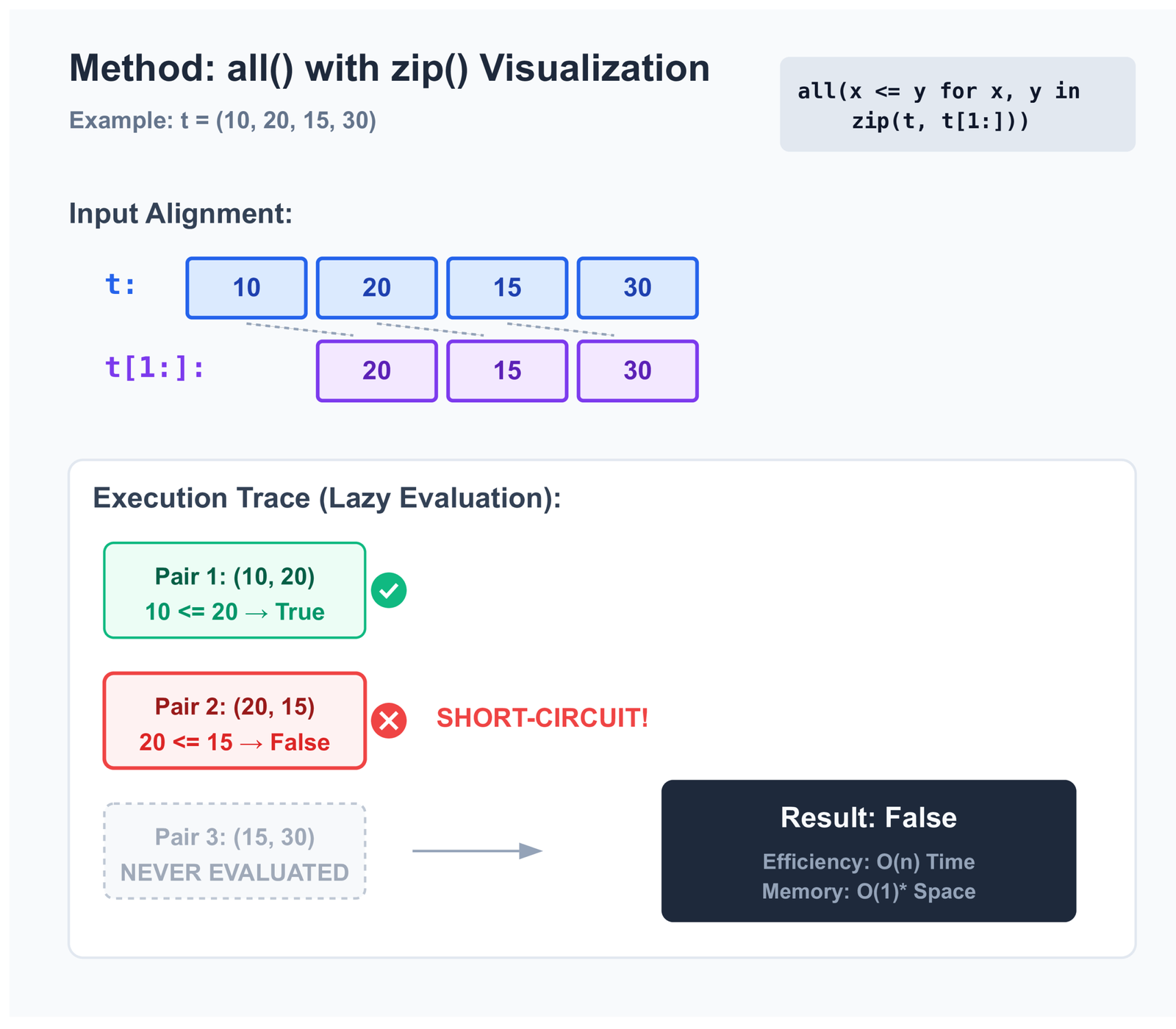

zip(t, t[1:]) pairs each element with the one that follows it. The tuple (10, 20, 15, 30) produces the pairs (10, 20), (20, 15), (15, 30). The generator inside all() evaluates them lazily, stopping immediately at the first False.

t[1:] = (20, 15, 30)

Pair (10, 20) → 10 <= 20 → True

Pair (20, 15) → 20 <= 15 → False → exits immediately

Pair (15, 30) → never evaluated

Slicing a tuple with t[1:] creates a new tuple object in memory, which is why the space is marked O(1)*. For tuples with tens of millions of elements that is a meaningful allocation, but for typical sizes it is not a concern. If memory matters, Method 4 (pairwise) avoids the slice entirely.

Strictly increasing variant

def is_strictly_sorted(t):

return all(x < y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:]))

Change <= to <. Now (1, 2, 2, 3) returns False because 2 is not strictly less than 2.

Try it — enter a tuple in JSON array format

Enter values as a JSON array, e.g. [1, 3, 5] or [4, 2, 7]

Method 2: For Loop — Clearest for Interviews

Time: O(n)Space: O(1)

def is_sorted(t):

for i in range(len(t) - 1):

if t[i] > t[i + 1]:

return False

return True

There are no built-in functions involved beyond range(). The logic is exactly what it looks like: iterate through adjacent pairs using an index, return False on the first violation, return True if none is found. Tuples support index access the same way lists do, so this transfers directly without modification.

i=0: t[0]=4, t[1]=9 → 4 > 9? No → continue

i=1: t[1]=9, t[2]=6 → 9 > 6? Yes → return False

i=2: t[2]=6, t[3]=11 → never reached

This is the version most interviewers expect to see first. It shows you understand what pairwise comparison means without relying on library functions. Once you present this, you can offer Method 1 as a more concise alternative. If you want to read more on how Python for loops work, including performance nuances, that is worth understanding before comparing the two.

i instead of False. With the all()-based methods, you would need to restructure the logic.

Method 3: all() with range() — When You Need the Index

Time: O(n)Space: O(1)

def is_sorted(t):

return all(t[i] <= t[i + 1] for i in range(len(t) - 1))

This combines the brevity of Method 1 with the index access of Method 2. It is useful when you want to extend the function to return positional information. For example, finding the first index where the order breaks:

def first_violation(t):

for i in range(len(t) - 1):

if t[i] > t[i + 1]:

return i # index of the first out-of-order element

return -1 # -1 means sorted

first_violation((1, 3, 2, 5, 4)) # Returns 1 (t[1]=3 > t[2]=2)

For developers more comfortable with index-based iteration — especially those coming from C, Java, or JavaScript — this form tends to be easier to reason about than zip(). Both are correct and have the same complexity.

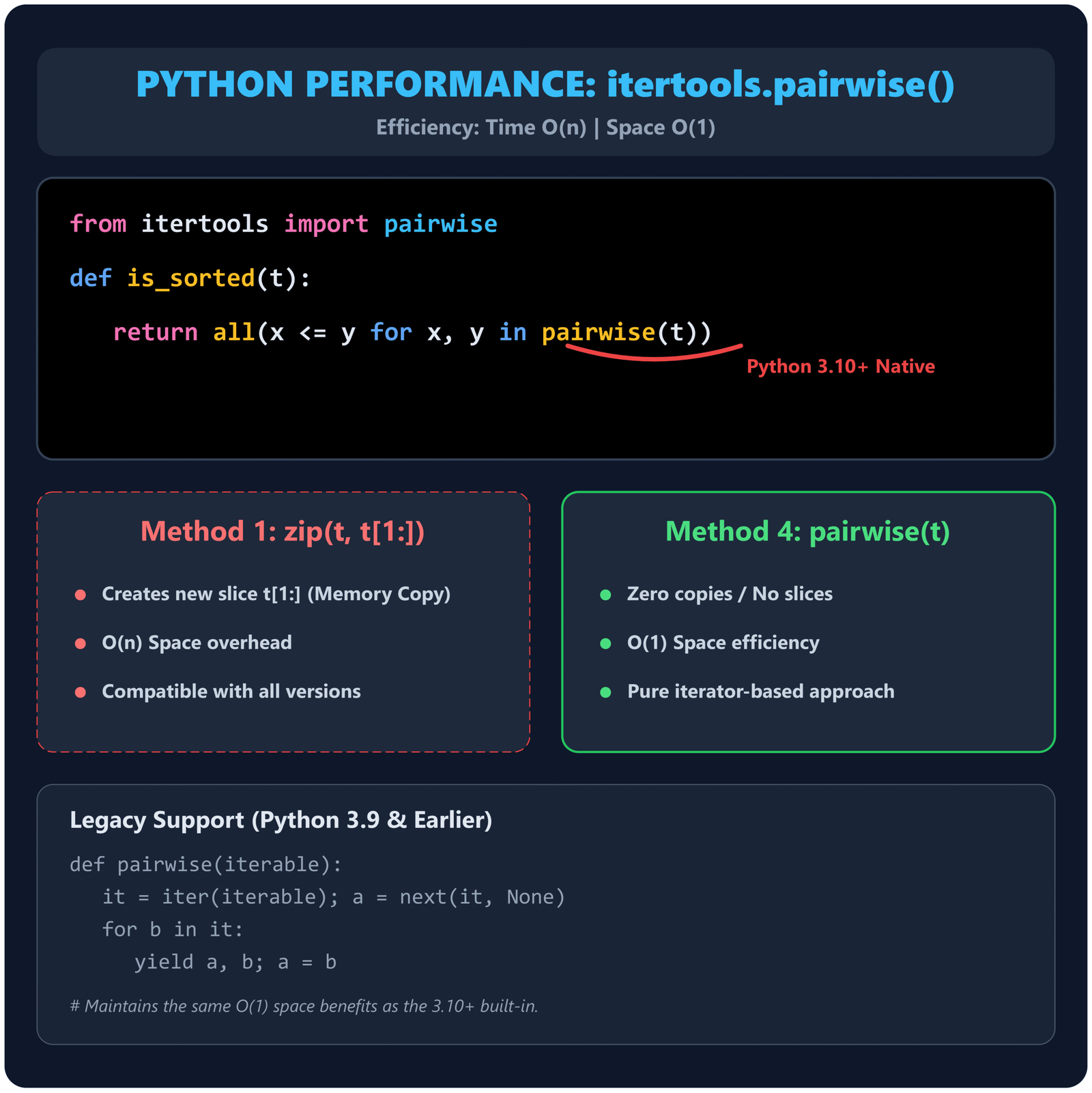

Method 4: itertools.pairwise() — Python 3.10 and Later

Time: O(n)Space: O(1)

from itertools import pairwise # Python 3.10+

def is_sorted(t):

return all(x <= y for x, y in pairwise(t))

itertools.pairwise() was added in Python 3.10 for exactly this kind of consecutive-pair iteration. It works on any iterable, including tuples, and produces adjacent pairs without creating any intermediate copies. Unlike Method 1 which slices the tuple with t[1:], pairwise() yields pairs directly from an iterator.

Each element stored twice in memory

Works in all Python versions

Pure iterator, O(1) space

Requires Python 3.10+

def pairwise(iterable):

it = iter(iterable)

a = next(it, None) # returns None if iterable is empty — no pairs yielded

for b in it:

yield a, b

a = b

# Empty or single-element input yields nothing, so all() returns True — correct behavior

Method 5: Using sorted() With a Comparison — Simplest But Least Efficient

Time: O(n log n)Space: O(n)

def is_sorted(t):

return t == tuple(sorted(t))

# For descending

def is_sorted_desc(t):

return t == tuple(sorted(t, reverse=True))

This is the most readable approach and the one most beginners reach for first. It sorts the tuple, converts the result back to a tuple, and compares against the original. The problem is that sorted() runs in O(n log n) time and allocates O(n) memory for the new list regardless of whether the tuple was already sorted or completely reversed. There is no early exit.

That said, there are legitimate reasons to use it. If the tuple is small (under a few hundred elements), the overhead is negligible. If your code already calls sorted() for another reason in the same block, adding this comparison costs almost nothing. And if clarity matters more than performance in that particular context, the intent is immediately obvious.

Checking for Descending Order

Flip the comparison operator. The method is otherwise identical to ascending checks.

def is_non_increasing(t):

return all(x >= y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:]))

def is_strictly_decreasing(t):

return all(x > y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:]))

is_non_increasing((10, 8, 8, 5, 2)) # True — duplicate 8 is allowed

is_strictly_decreasing((10, 8, 8, 5, 2)) # False — duplicate 8 fails strict check

is_strictly_decreasing((10, 8, 5, 2)) # True

Checking Sorted Order by a Specific Key

Tuples frequently store structured records — coordinates, database rows, named data. You may need to check whether a sequence of tuples is sorted by a specific field rather than by overall tuple value.

records = (

("Alice", 28, 72000),

("Bob", 34, 85000),

("Priya", 31, 91000),

)

# Check if sorted by salary (index 2)

def is_sorted_by(t, key):

return all(key(x) <= key(y) for x, y in zip(t, t[1:]))

is_sorted_by(records, key=lambda r: r[2]) # True — salaries: 72k, 85k, 91k

is_sorted_by(records, key=lambda r: r[1]) # False — ages: 28, 34, 31

The same pattern works with operator.itemgetter(), which is marginally faster than a lambda for attribute or index access:

import operator is_sorted_by(records, key=operator.itemgetter(2)) # True — sorted by salary

This pattern is common when validating that a dataset has been correctly ordered before processing, without needing to re-sort it.

Edge Cases

Empty tuples and single-element tuples

Both return True from all methods that use zip() or pairwise(). An empty iterable produces no pairs, and all() returns True for empty input by definition. A single-element tuple has no adjacent pair to compare, so it is trivially sorted.

is_sorted(()) # True is_sorted((99,)) # True

This is the mathematically correct answer and is consistent with how Python's standard library handles it. If your specific use case requires at least two elements, add an explicit check at the start of your function.

Tuples with duplicate values

The choice of operator determines how duplicates are handled. Make sure you are using the right one for your situation.

t = (1, 2, 2, 3) all(x <= y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:])) # True — non-decreasing, duplicates ok all(x < y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:])) # False — strictly increasing, 2==2 fails

Choose <= if your definition of sorted allows plateaus (consecutive equal values). Use < if every element must be strictly larger than the one before it.

Mixed types raise TypeError

t = (1, 2, "three", 4) is_sorted(t) # TypeError: '<' not supported between instances of 'str' and 'int'

Python 3 does not coerce types during comparison. If your tuple could contain mixed types from external sources — user input, parsed files, or type conversions — wrap the check in a try-except:

def is_sorted_safe(t):

try:

return all(x <= y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:]))

except TypeError:

return False

For more complex custom comparison logic — for example, sorting objects that have no natural ordering — functools.cmp_to_key() is worth knowing. It converts an old-style comparison function (one that returns negative, zero, or positive) into a key function compatible with Python's sorting and comparison tools. That said, it is an advanced pattern and most sorted-checking scenarios are better served by the simple lambda or operator.attrgetter() approach shown in the key-based section above.

Tuples of tuples (lexicographic comparison)

Python compares tuples lexicographically by default, meaning it compares the first element of each pair, then the second if the first elements are equal, and so on. This behavior is useful when your data is naturally ordered that way, but it can produce unexpected results when you intend to sort by a specific position.

nested = ((1, 9), (2, 3), (2, 7), (3, 1)) # Default tuple comparison is lexicographic is_sorted(nested) # True — (1,9) < (2,3) < (2,7) < (3,1) by first element first, then second # But if you want to sort by second element only: is_sorted_by(nested, key=lambda x: x[1]) # False — second elements are 9, 3, 7, 1 which is not sorted

None values

None cannot be compared with numbers in Python 3. If your tuple contains None values — common in data pipelines where missing entries exist — handle them explicitly. More on this in our article on handling missing values in data science.

def compare(x, y):

if x is None: return True # None sorts first

if y is None: return False

return x <= y

def is_sorted_with_none(t):

return all(compare(x, y) for x, y in zip(t, t[1:]))

is_sorted_with_none((None, 1, 3, 5)) # True

is_sorted_with_none((1, None, 3, 5)) # False

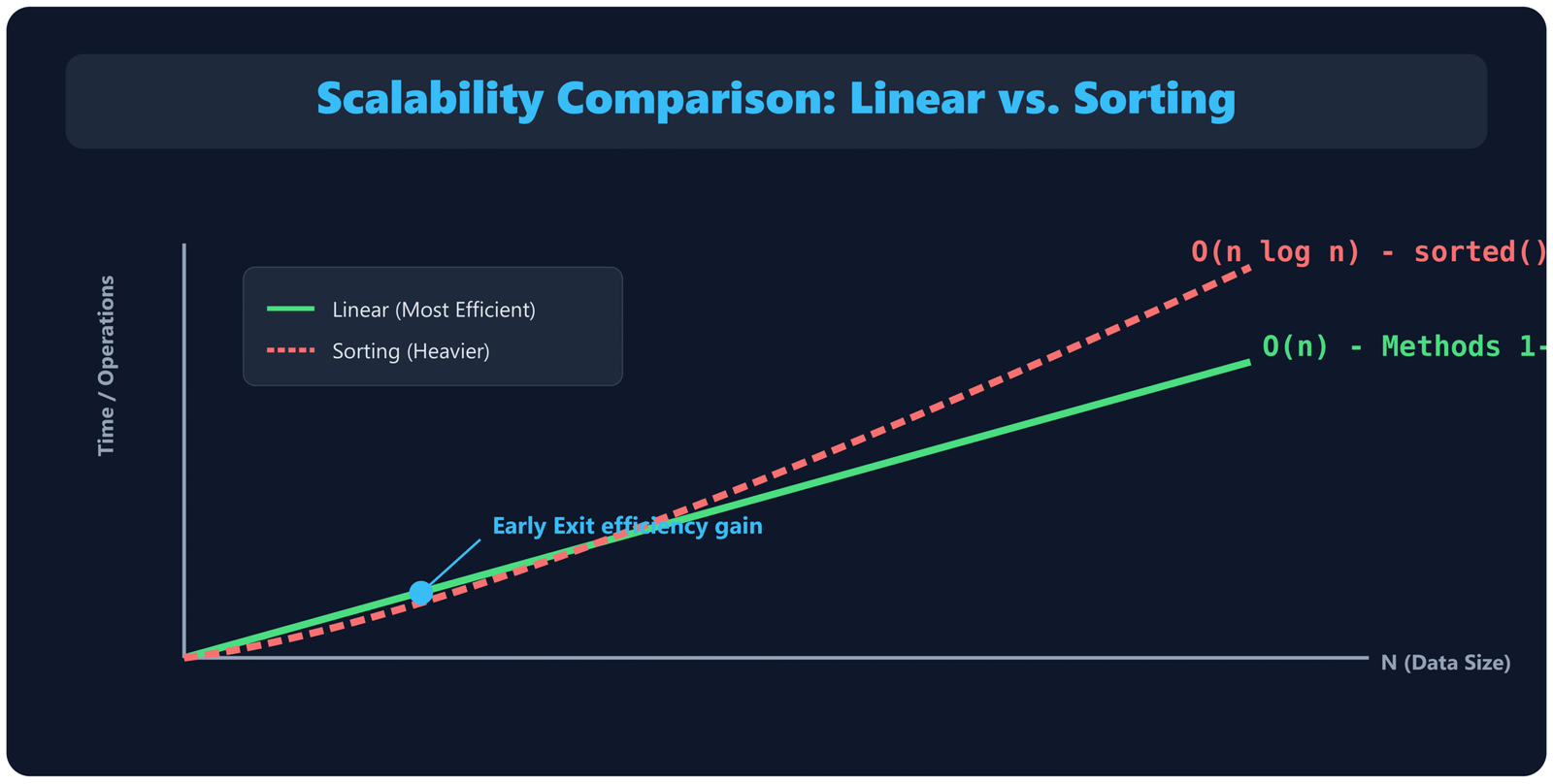

Performance Comparison

| Method | Time | Space | Early Exit | Python | Best Used When |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| all() + zip() | O(n) | O(n)* | Yes | Any | General use, works everywhere |

| for loop | O(n) | O(1) | Yes | Any | Interviews, need for index access |

| all() + range() | O(n) | O(1) | Yes | Any | Need index, prefer one-liner style |

| pairwise() | O(n) | O(1) | Yes | 3.10+ | Python 3.10+, best memory efficiency |

| sorted() comparison | O(n log n) | O(n) | No | Any | Small tuples, clarity over performance |

*The O(n) space for zip(t, t[1:]) comes from the tuple slice t[1:], which allocates a new tuple. Since tuples store references (not object copies), this is one pointer per element — lightweight but nonzero. For large tuples where this matters, use the for loop or pairwise().

Benchmarking the methods yourself

The standard library's timeit module is the right tool for measuring these differences on your own machine and Python version. Here is a script you can run directly:

import timeit

from itertools import pairwise

# Build a large mostly-sorted tuple with one violation in the middle

base = list(range(1_000_000))

base[500_000] = 0 # single violation at position 500k

t = tuple(base)

def is_sorted_zip(t):

return all(x <= y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:]))

def is_sorted_loop(t):

for i in range(len(t) - 1):

if t[i] > t[i + 1]:

return False

return True

def is_sorted_range(t):

return all(t[i] <= t[i + 1] for i in range(len(t) - 1))

def is_sorted_pairwise(t): # Python 3.10+

return all(x <= y for x, y in pairwise(t))

def is_sorted_sorted(t):

return t == tuple(sorted(t))

n = 5

for label, fn in [

("zip + all ", is_sorted_zip),

("for loop ", is_sorted_loop),

("range + all ", is_sorted_range),

("pairwise ", is_sorted_pairwise),

("sorted() ", is_sorted_sorted),

]:

secs = timeit.timeit(lambda: fn(t), number=n)

print(f"{label} {secs/n*1000:.1f} ms per call")

On a typical machine, the four O(n) methods all complete in roughly the same time for a million-element tuple — the violation at position 500k means they each check about 500k pairs before exiting. The sorted() method will be noticeably slower because it never exits early and must sort the entire tuple first. Run it yourself; the exact numbers depend on your hardware, Python version, and how early in the tuple the first violation appears.

pairwise lines if your environment is on Python 3.9 or earlier.

The right choice between Methods 1–4 comes down to Python version, whether you need index access, and what makes the code most readable for your team — not raw speed.

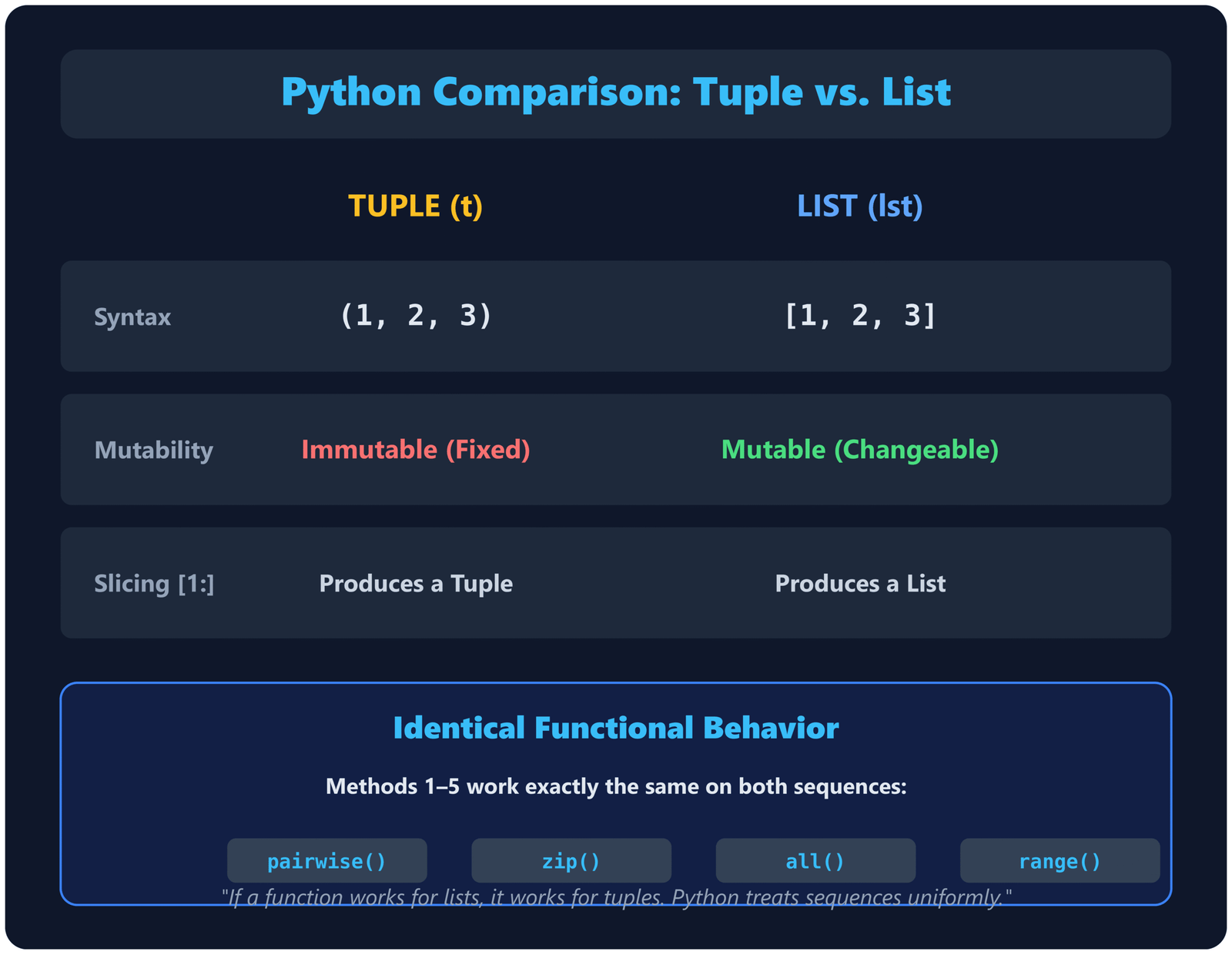

Tuple vs List: Does the Method Change?

Not meaningfully. All five methods work on both tuples and lists without modification because Python's zip(), pairwise(), range(), and index access all treat sequences uniformly. The only real difference is that slicing produces a tuple from a tuple and a list from a list.

lst[1:] produces a list

zip(lst, lst[1:]) works fine

t[1:] produces a tuple

zip(t, t[1:]) works fine

The functional behavior is identical. If you have a function written for lists, it will work on tuples without changes. If you want to learn more about the differences between these two data structures, see our guide on Python tuples.

External Resources

- Python Docs — Tuple type — Official documentation covering tuple operations, including slicing and sequence behavior used across all five methods.

- Python Docs — all() — Reference for the built-in function, including the short-circuit behavior that makes Methods 1, 3, and 4 efficient.

- Python Docs — itertools.pairwise() — Official documentation for the pairwise function added in Python 3.10.

- Python Docs — operator.itemgetter() — Reference for extracting tuple fields by index, used in key-based sorted checks.

- Stack Overflow — Pythonic way to check if a sequence is sorted — Community thread covering lists and tuples with edge cases and performance discussion.

-

Real Python — Python's all() function

— In-depth look at using

all()with generator expressions, relevant to Methods 1, 3, and 4. - Python Docs — Comparisons — Explains how Python compares tuples lexicographically, which matters when checking tuples of tuples.

- Python Wiki — Time Complexity — Official reference for the time complexity of common Python operations including sorting and slicing.

GitHub Repository: python-tuple-sorted-check

Complete runnable code for all 5 methods, descending variants, key-based checks, safe error handling, test cases, and performance benchmarks shown in this article.

Explore More: Dive deeper with these from EmiTechLogic

- Python Tuples – Everything You Need to Know → Deep dive into tuples: immutability, methods, use cases

- Check if List is Sorted in Python → Similar techniques adapted for mutable lists + performance tips

More Python & AI resources at EmiTechLogic.com

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you check if a tuple is sorted in Python without sorting it?

Use all(x <= y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:])). This compares each element with the next one using a lazy generator expression, so it exits immediately when it finds an out-of-order pair. It runs in O(n) time in the worst case and requires no sorting, no copies of the full data, and no additional data structures. For Python 3.10+, itertools.pairwise() provides the same result with slightly better memory efficiency.

Can you use sort() to check if a tuple is sorted in Python?

Tuples do not have a sort() method — calling it raises an AttributeError. You can use sorted(), which works on any iterable, but it returns a list and requires converting back to a tuple for comparison: t == tuple(sorted(t)). This works but is O(n log n) and allocates O(n) memory, making it significantly less efficient than pairwise comparison methods for large tuples.

How do you check if a tuple of tuples is sorted in Python?

Python compares tuples lexicographically by default — first by the first element, then by the second if the first elements are equal, and so on. If that is the order you want, all(x <= y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:])) works directly. If you want to sort by a specific field, use a key function: all(key(x) <= key(y) for x, y in zip(t, t[1:])) where key is a lambda or operator.itemgetter(i).

What is the time complexity of checking if a tuple is sorted?

O(n) in the worst case, where n is the number of elements. That worst case occurs when the tuple is fully sorted and every pair must be checked. In the best case — the first pair is out of order — the function exits after a single comparison. For random unsorted data, you can expect to check roughly 50% of pairs on average before hitting a violation. This is fundamentally more efficient than sort-based approaches, which are O(n log n) regardless of input.

Does the same method work for both tuples and lists in Python?

Yes. All the methods described here — zip(), pairwise(), range()-based loops, and key-based comparisons — work on both tuples and lists without modification. Python treats both as sequences, so slicing, indexing, and iteration behave the same way. The only difference is that slicing a tuple produces a tuple, while slicing a list produces a list — but both work correctly inside zip().

Test Your Understanding

Ten questions on checking sorted order in Python tuples. Each answer is checked individually when you submit.

1. Which method raises an AttributeError when called on a tuple?

2. What does all(x <= y for x, y in zip(t, t[1:])) return for an empty tuple ()?

3. Which operator checks for strictly increasing order with no duplicates allowed?

4. What is the time complexity of t == tuple(sorted(t)) for checking sorted order?

5. What does is_sorted((5, 5, 5)) return using the <= operator?

6. Which Python version introduced itertools.pairwise()?

7. How does Python compare tuples of tuples by default?

8. What happens when you call is_sorted((1, "two", 3)) in Python 3?

9. Which operator should you use to check non-increasing (descending with duplicates allowed) order?

10. You have a tuple of employee records and want to check if they are sorted by salary (index 2). Which approach is correct?

Leave a Reply