How to Check If a List Is Sorted in Python (Without Using sort()) – 5 Efficient Methods

Never Sort Just to Check Order: 5 Efficient O(n) Methods in Python()

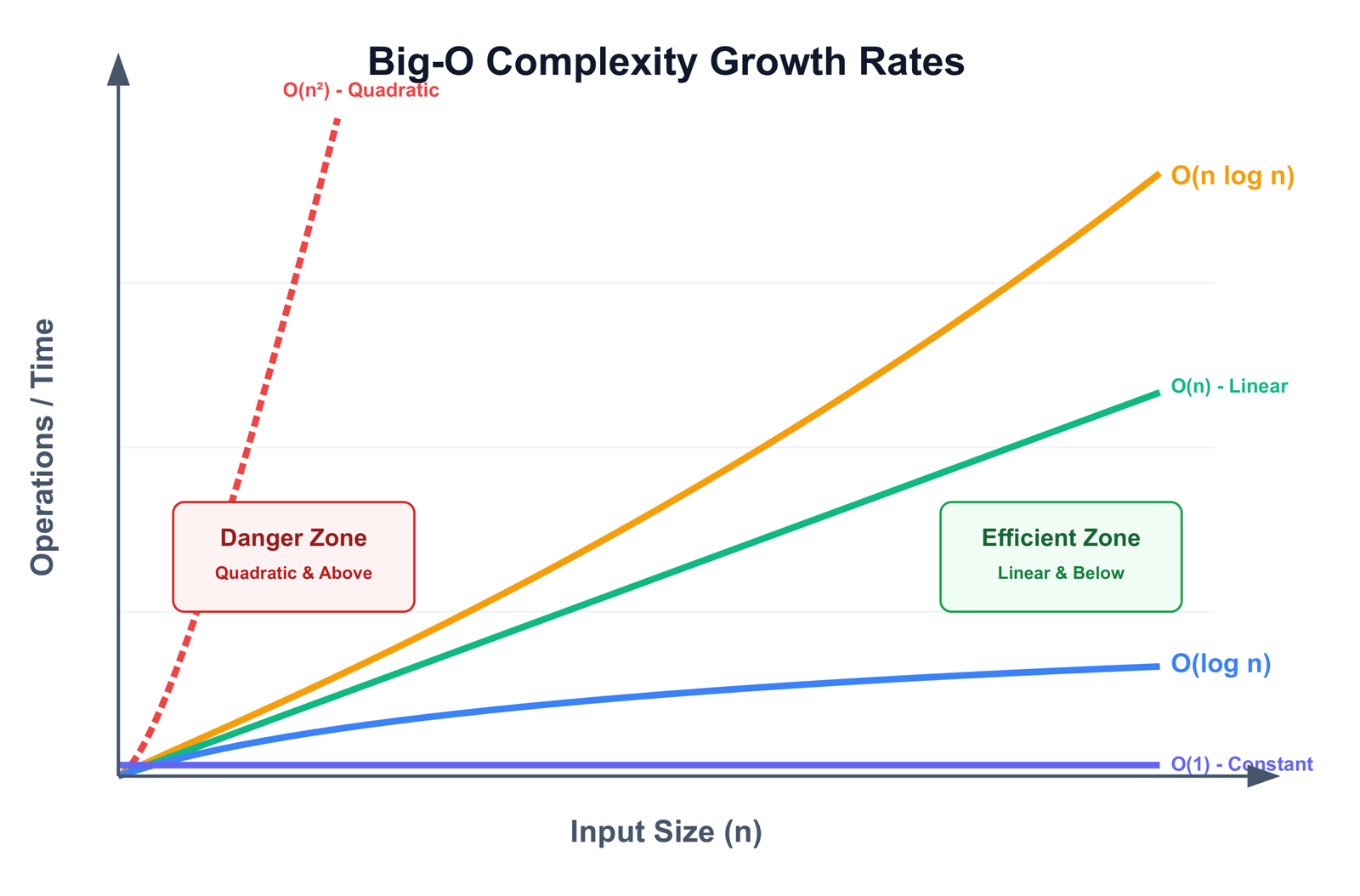

The Problem With Using sort() Just to Verify Order

There is a subtle but costly mistake that appears in a lot of Python code: using sort() or sorted() just to check whether a list is already sorted. The most common version looks like this:

# Don't do this for validation

def is_sorted_bad(lst):

return lst == sorted(lst)

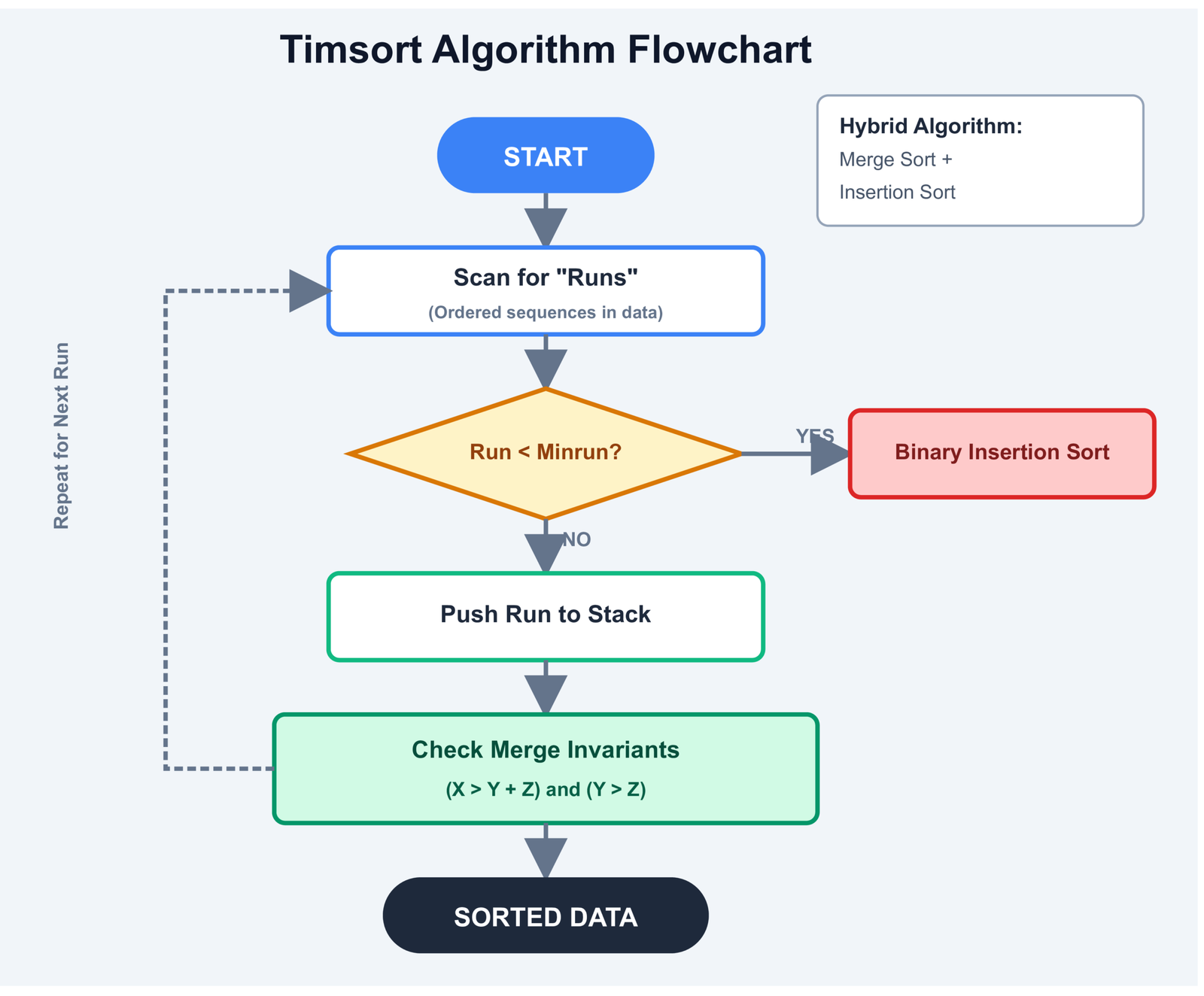

The problem is that Python’s sorting algorithm (Timsort) runs in O(n log n) time and creates an entirely new list in memory. If you have a million-element list, that is roughly 20 million comparison operations and a full copy of the list — just to answer a yes or no question. When the list is already sorted, that is pure waste.

The five methods below all run in O(n) time and stop the moment they find the first out-of-order pair. No unnecessary work, no copies.

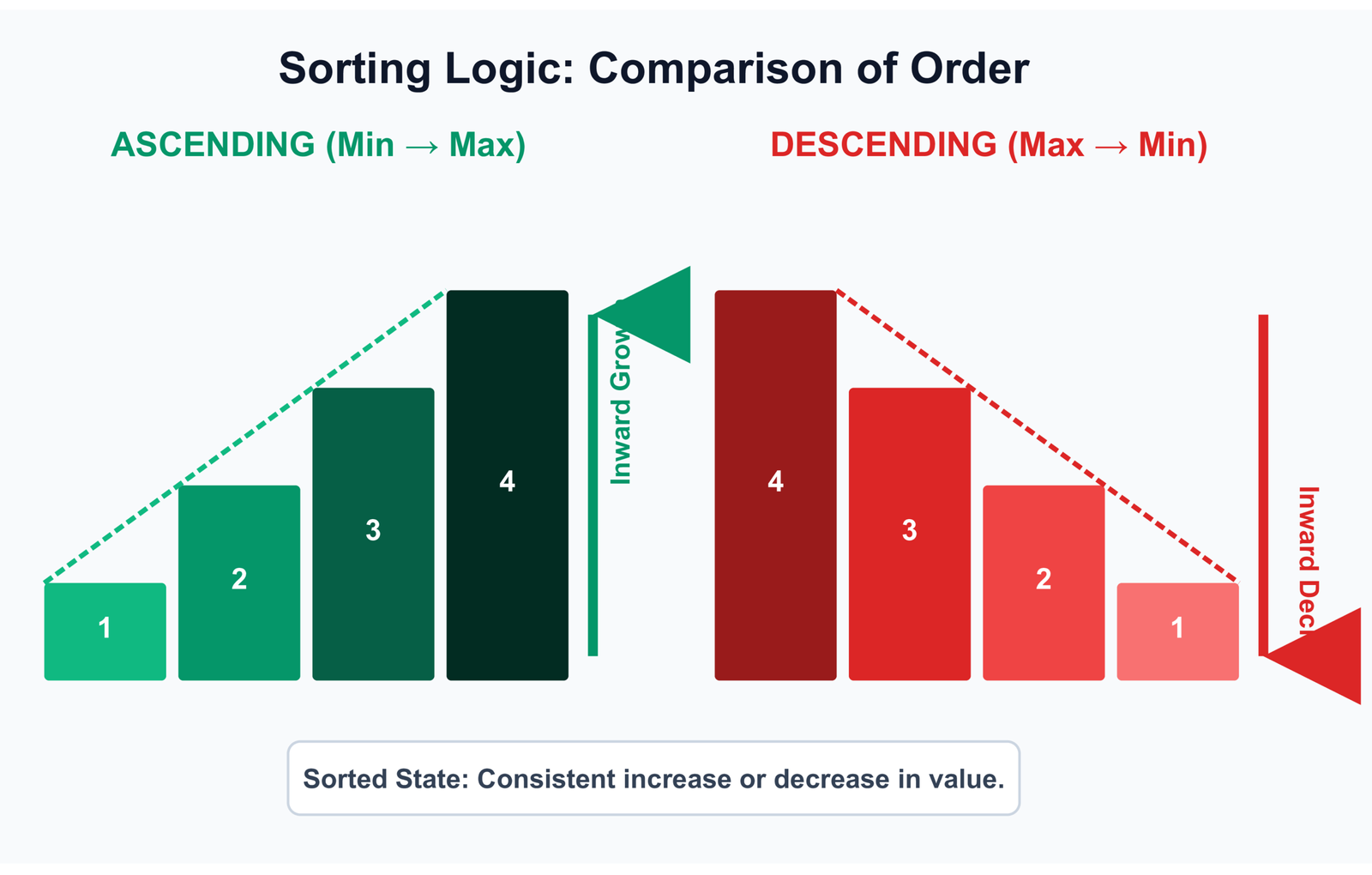

Understanding What “Sorted” Means Before Writing Code

This sounds obvious, but it is worth being precise. There are two distinct definitions most developers conflate:

- Non-decreasing — each element is less than or equal to the next. Duplicates are allowed.

[1, 2, 2, 3]qualifies. - Strictly increasing — each element must be strictly less than the next. No duplicates.

[1, 2, 2, 3]does not qualify.

The same distinction applies to descending order: non-increasing (allows duplicates) versus strictly decreasing (no duplicates). The only difference in code is the comparison operator you use: <= vs <, or >= vs >.

TypeError. Custom objects need __lt__ or __le__ defined. We cover both edge cases at the end of the article.

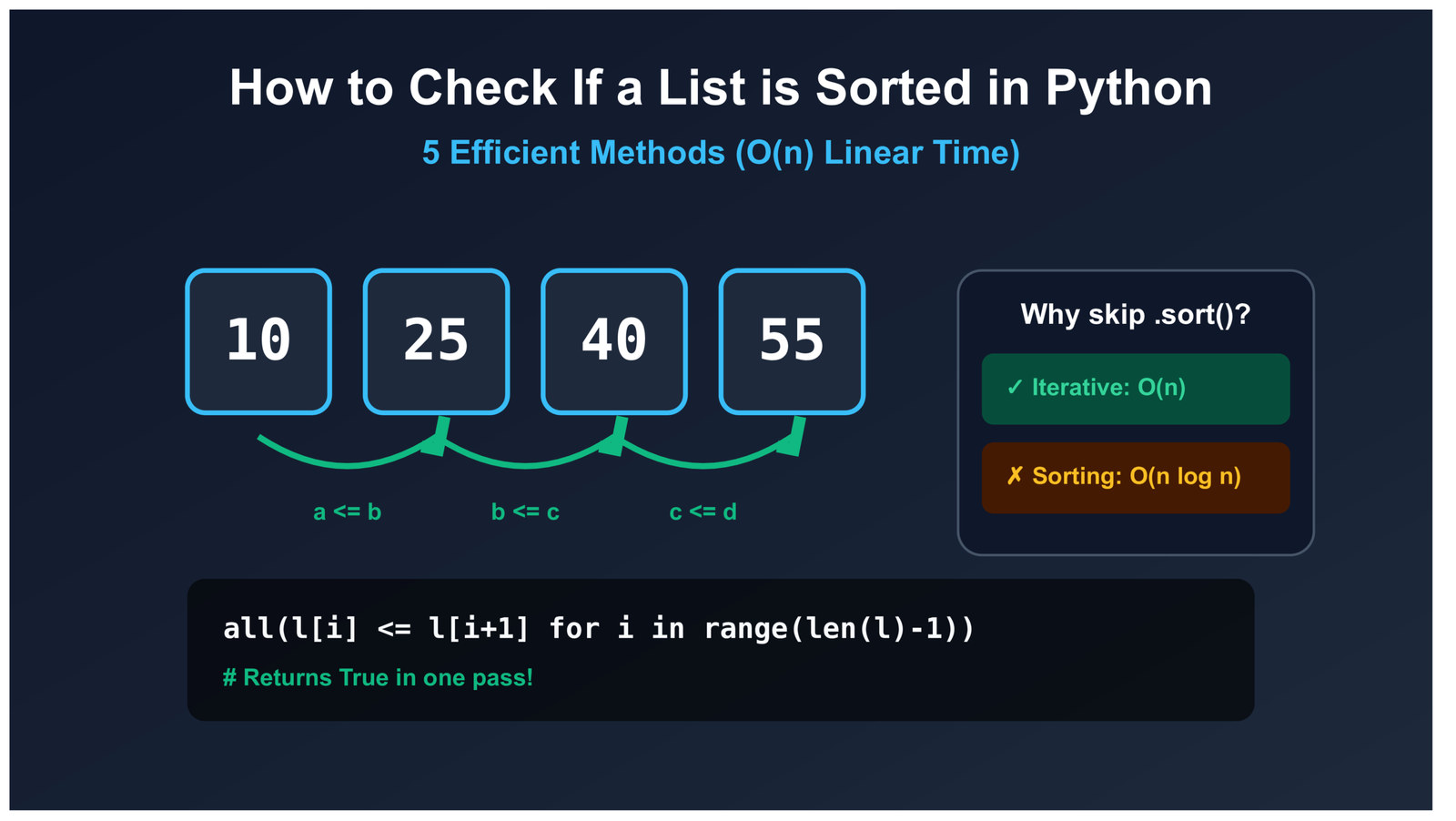

Method 1: all() with zip() — The Standard Approach

Time: O(n)Space: O(1)*

def is_sorted(lst):

return all(x <= y for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:]))

# For strictly increasing (no duplicates)

def is_strictly_sorted(lst):

return all(x < y for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:]))

How the pairing works

zip(lst, lst[1:]) pairs each element with the one that follows it. The first argument provides elements at indices 0, 1, 2, and so on. The second argument — lst[1:] — provides elements starting from index 1. The result is an iterator of (lst[i], lst[i+1]) tuples without ever building the full pair list in memory.

lst[1:] = [5, 7, 4, 9]

Pair (3, 5) → 3 <= 5 → True

Pair (5, 7) → 5 <= 7 → True

Pair (7, 4) → 7 <= 4 → False → exits here

Pair (4, 9) → never evaluated

The generator inside all() is lazy. As soon as one comparison returns False, all() short-circuits and returns False immediately. The remaining pairs are never evaluated.

*The asterisk on space: lst[1:] does create a shallow slice copy, which technically uses O(n) memory. If you're working with very large lists and memory is a genuine constraint, use Method 4 (pairwise()) which avoids the slice entirely.

Try it — enter any list in JSON format

Method 2: For Loop — Clearest for Interviews

Time: O(n)Space: O(1)

def is_sorted(lst):

for i in range(len(lst) - 1):

if lst[i] > lst[i + 1]:

return False

return True

This is the most explicit version. There are no built-in functions to reason about — just a loop, an index comparison, and an early return. The conditional logic is visible at a glance, which makes it the preferred choice when explaining the approach in a technical interview.

i=0: lst[0]=2, lst[1]=4 → 2 > 4? No → continue

i=1: lst[1]=4, lst[2]=3 → 4 > 3? Yes → return False

i=2: never reached

Performance-wise, it is equivalent to Method 1. The gap between the two is statistical noise when benchmarked on real lists. The difference is purely stylistic: Method 1 reads more concisely; Method 2 exposes the mechanism.

zip() one-liner as an alternative. It signals that you can write readable code at different levels of abstraction.

Method 3: all() with range() — When You Need the Index

Time: O(n)Space: O(1)

def is_sorted(lst):

return all(lst[i] <= lst[i + 1] for i in range(len(lst) - 1))

Functionally nearly identical to Method 1, but index-based. The main reason to choose this over zip() is when you need to extend it — for example, to return the index of the first violation rather than just a boolean:

def first_unsorted_index(lst):

for i in range(len(lst) - 1):

if lst[i] > lst[i + 1]:

return i

return -1

first_unsorted_index([1, 3, 2, 5]) # Returns 1

For developers coming from C, Java, or other index-heavy languages, this pattern tends to feel more natural than the zip() idiom. Both are valid; pick the one that makes the code clearer to your team. See our article on Python's range function for more on index-based iteration patterns.

Method 4: itertools.pairwise() — Python 3.10+

Time: O(n)Space: O(1)

from itertools import pairwise # Python 3.10+

def is_sorted(lst):

return all(x <= y for x, y in pairwise(lst))

Python 3.10 added itertools.pairwise() to the standard library precisely for this kind of consecutive-pair iteration. Unlike Method 1, it does not create a slice copy of the list. It yields pairs directly from the iterator, which means genuine O(1) auxiliary space.

def pairwise(iterable):

it = iter(iterable)

a = next(it, None)

for b in it:

yield a, b

a = b

For new code targeting Python 3.10+, this is the cleanest option. It is explicit about intent (pairwise says exactly what it does), avoids the slice, and reads well. For code that needs to stay compatible with earlier versions, stick with Method 1.

Method 5: operator.le — For Custom Object Comparisons

Time: O(n)Space: O(1)*

import operator

def is_sorted(lst):

return all(operator.le(x, y) for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:]))

This is Method 1 written with operator.le instead of the inline <= expression. On its own that is not very useful, but the pattern becomes valuable when you need to pass comparison logic as a parameter — for example, checking whether a list of custom objects is sorted by a specific attribute:

import operator

class Employee:

def __init__(self, name, salary):

self.name = name

self.salary = salary

def is_sorted_by(lst, key):

return all(key(x) <= key(y) for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:]))

employees = [

Employee("Ana", 40000),

Employee("David", 55000),

Employee("Priya", 72000),

]

is_sorted_by(employees, key=operator.attrgetter("salary")) # True

This pattern is common in data processing work where you need to verify sorted order on a specific field without modifying class internals or adding comparison methods. operator.attrgetter() is marginally faster than a lambda for attribute access and is the standard approach in the Python standard library itself.

Checking for Descending Order

Flip the operator. Non-increasing order (duplicates allowed) uses >=; strictly decreasing uses >:

def is_non_increasing(lst):

return all(x >= y for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:]))

def is_strictly_decreasing(lst):

return all(x > y for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:]))

is_non_increasing([10, 8, 8, 5, 2]) # True (duplicate 8 allowed)

is_strictly_decreasing([10, 8, 8, 5, 2]) # False (duplicate 8 fails)

Edge Cases Worth Knowing

Empty lists and single-element lists

Both return True from all five methods. zip() produces no pairs from an empty or single-element list, and all() returns True for empty iterables by definition. This is the mathematically correct behavior and is consistent with how Python's own sorted() handles it.

is_sorted([]) # True is_sorted([42]) # True

Duplicate values

Using <= accepts duplicates; using < rejects them. Make sure you are using the right operator for your use case. A list of equal timestamps should pass a non-decreasing check. A list of unique database IDs should fail it.

Mixed types raise TypeError

is_sorted([1, 2, "three", 4]) # TypeError: '<' not supported between instances of 'str' and 'int'

Python 3 does not silently convert types during comparison. If your input could be mixed — from user uploads, external APIs, or scraped data — validate types before checking order:

def is_sorted_safe(lst):

try:

return all(x <= y for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:]))

except TypeError:

return False

None values

None cannot be compared with integers or strings in Python 3. If your data contains None — common in data cleaning workflows — you need to decide how to treat it. A common convention is to treat None as negative infinity (sorts first):

def compare(x, y):

if x is None: return True

if y is None: return False

return x <= y

def is_sorted_with_none(lst):

return all(compare(x, y) for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:]))

is_sorted_with_none([None, 1, 3, 5]) # True

is_sorted_with_none([1, None, 3, 5]) # False

For broader strategies on dealing with missing data, see our article on handling missing values in data science.

Performance Comparison

| Method | Time | Space | Python | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| all() + zip() | O(n) | O(n)* | Any | Most commonly used, readable |

| for loop | O(n) | O(1) | Any | Best for interviews and clarity |

| all() + range() | O(n) | O(1) | Any | Useful when index is needed |

| pairwise() | O(n) | O(1) | 3.10+ | No slice copy, cleanest option |

| operator.le | O(n) | O(n)* | Any | Best for custom objects and key-based sorting |

*The O(n) space note for zip()-based methods comes from the lst[1:] slice. It is a shallow copy of references, not a deep copy of objects, so in practice the overhead is one pointer per element. For most use cases this is not a concern. If it is, use the for loop or pairwise().

In terms of raw speed, all five Python methods produce benchmarks within a few percent of each other on the same hardware. The choice between them should be driven by readability, Python version, and whether you need index access — not by micro-performance differences. For a deeper look at writing efficient Python code, see our guide on Python optimization.

When to Use NumPy or Pandas Instead

If you are already working with NumPy arrays or Pandas DataFrames, do not convert to Python lists just to use the methods above. Both libraries have native solutions that are significantly faster.

NumPy arrays

import numpy as np arr = np.array([1, 3, 5, 7, 9]) np.all(arr[:-1] <= arr[1:]) # True

This performs element-wise comparison entirely in C through NumPy's vectorized operations. It is typically 30-50x faster than any Python loop approach on large arrays. arr[:-1] and arr[1:] are views — no copies are made. For more on working with NumPy, see our guide on data analysis with NumPy and Pandas.

Pandas Series and DataFrames

import pandas as pd s = pd.Series([10, 15, 20, 25]) s.is_monotonic_increasing # True — non-decreasing s.is_monotonic_decreasing # False # Strictly increasing: non-decreasing AND all unique s.is_monotonic_increasing and s.is_unique # True

Pandas implements is_monotonic_increasing and is_monotonic_decreasing in Cython. They are the idiomatic and fastest way to check sorted order in a Pandas context. Using Python loops on a Pandas Series is slower and less readable. For more context, see data analysis using Pandas.

One scenario where sort() is actually better

If you need the sorted list anyway regardless of its current order, skip the check entirely and just sort:

# Unnecessary check before sorting

if not is_sorted(data):

data.sort()

# Just sort it — Timsort runs in O(n) on already-sorted data

data.sort()

Timsort detects ascending runs in the input and handles already-sorted lists in O(n) time. Adding a verification pass before it only adds overhead.

External Resources

-

Python Docs — built-in all()

— Official reference for the

all()function used across several methods above. -

Python Docs — itertools.pairwise()

— Official documentation for the

pairwise()function added in 3.10. -

Python Docs — operator module

— Full reference for

operator.le,attrgetter, and related utilities used in Method 5. - NumPy Docs — numpy.all() — Reference for the vectorized all-elements check used in NumPy sorted verification.

- Pandas Docs — Series.is_monotonic_increasing — Official documentation for the Pandas monotonicity property.

- Stack Overflow — Pythonic way to check if a list is sorted — Long-running community thread with edge cases and alternative approaches.

- Wikipedia — Timsort — Explains why Python's sort performs in O(n) on already-sorted data, which affects the decision of when to skip the check.

-

Real Python — Python's all() function

— Practical walkthrough of

all()with generator expressions, which underpins Methods 1, 3, and 4.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most efficient way to check if a list is sorted in Python without using sort()?

For standard Python lists, all(x <= y for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:])) is the standard choice — O(n) time with early exit. If you are on Python 3.10 or later, itertools.pairwise() is marginally better on memory because it avoids creating a slice copy. For NumPy arrays, np.all(arr[:-1] <= arr[1:]) is around 30-50x faster. For Pandas, series.is_monotonic_increasing is the correct tool.

How do you check if a Python list is sorted in descending order?

Replace the <= with >=: all(x >= y for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:])). This checks for non-increasing order, where duplicates are allowed. For strictly decreasing order (no duplicates), use > instead of >=. The logic is identical to ascending checks; only the operator changes.

Does Python's all() function short-circuit when checking sorted order?

Yes. When all() is given a generator expression, it evaluates elements one at a time. The moment it encounters a False value, it returns False immediately without evaluating the rest of the generator. This is what makes these methods efficient for partially sorted data — they stop at the first out-of-order pair.

What is the time complexity of checking if a list is sorted in Python?

O(n) in the worst case (list is fully sorted, every pair must be checked). In the best case — reverse-sorted data — it exits after just one comparison. In practice, random unsorted data will exit after checking roughly 50% of pairs on average. This compares favorably to sort()-based approaches which are O(n log n) regardless of input order.

How do you check if a Pandas DataFrame column is sorted in Python?

Use df['column'].is_monotonic_increasing for ascending order or df['column'].is_monotonic_decreasing for descending. For strictly increasing (no duplicates), combine both checks: df['column'].is_monotonic_increasing and df['column'].is_unique. These properties are implemented in Cython and are the recommended approach — avoid running Python loops on Pandas Series.

Test Your Understanding

Ten questions covering the key concepts from this article. Answers are checked immediately after each submission.

1. What is the time complexity of Python's sort() method?

2. What does all(x < y for x, y in zip(lst, lst[1:])) check for?

3. What does is_sorted([]) return using the zip() method?

4. Which Python version introduced itertools.pairwise()?

5. What happens when you call is_sorted([1, 2, "three"]) in Python 3?

6. Why is pairwise() considered more memory-efficient than zip(lst, lst[1:])?

7. Which Pandas property checks if a Series is in non-decreasing order?

8. Which operator checks for non-increasing (descending with duplicates allowed) order?

9. What is the recommended way to check if a NumPy array is sorted?

10. When is it better to just call data.sort() rather than checking first with is_sorted()?

Your Score

Source Code

You can find the complete code on GitHub:

Emmimal/python-check-if-list-sorted

If this helped you, feel free to give it a ⭐ on GitHub!

Leave a Reply