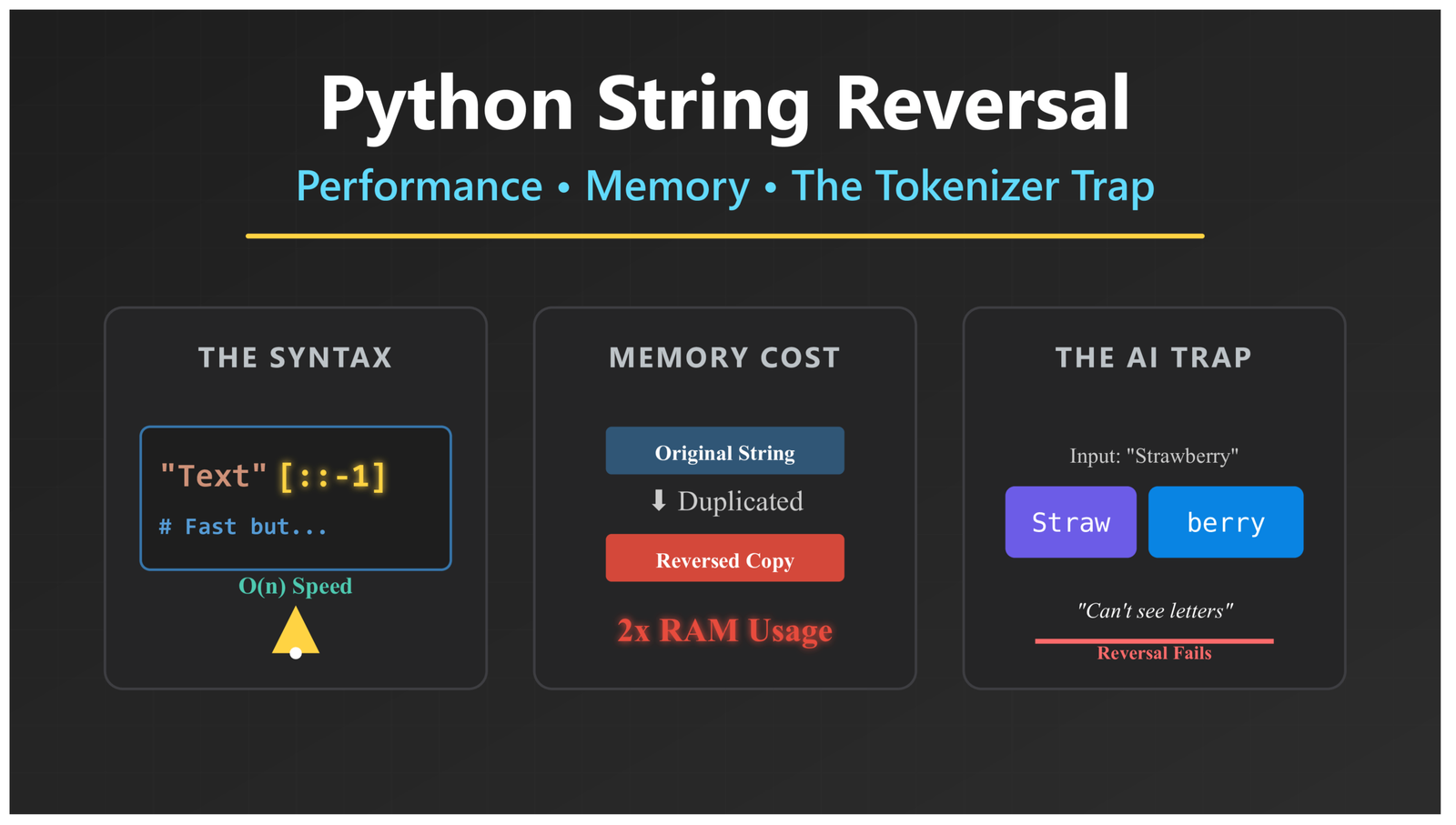

How to Reverse a String in Python: Performance, Memory, and the Tokenizer Trap

Python String Reversal: Performance, Memory Efficiency & Why AI Models Fail

Why String Reversal in Python Reveals Critical Performance and AI Limitations

Reversing a string is one of the first things you learn in Python. It seems simple. But this basic task actually teaches us something important about how computers use memory and why AI tools like ChatGPT struggle with certain problems.

Think about it this way: when you reverse the word “Python” to get “nohtyP”, your computer can do this in different ways. Some ways are faster. Some ways use less memory. For a short word, it does not matter much. But what if you need to reverse a huge text file that is 500 megabytes? Suddenly, the method you choose makes a big difference.

In this article, we will look at three things. First, how Python actually reverses strings behind the scenes. Second, why some methods eat up your computer’s memory while others do not. Third, why AI language models often fail at this simple task—and what that tells us about building better AI systems.

When Does This Matter?

If you are just reversing a few words, any method works fine. But if you are building real software that processes server logs every minute, or you are working with DNA sequences in biology research, then choosing the right method becomes critical. Your program might crash if you pick the wrong approach.

(Related: Check my Python Optimization Guide: How to Write Faster, Smarter Code for more performance tips.)Understanding Python String Slicing with Step Notation for Reversal

Python has a clever way to work with strings

using something called slicing. When you write [::-1], you are telling Python: “Give me this string, but backwards.”

# The most common way to reverse a string in Python

original_string = "Python"

reversed_str = original_string[::-1]

# Result: "nohtyP"

How Python Interprets Negative Step Values in Slice Operations

Let me break down what [::-1] means. The full format for slicing is [start:stop:step]. When you leave start and stop empty, Python knows you want the whole string. The -1 at the end is the step size. A negative step tells Python to walk backwards through the string.

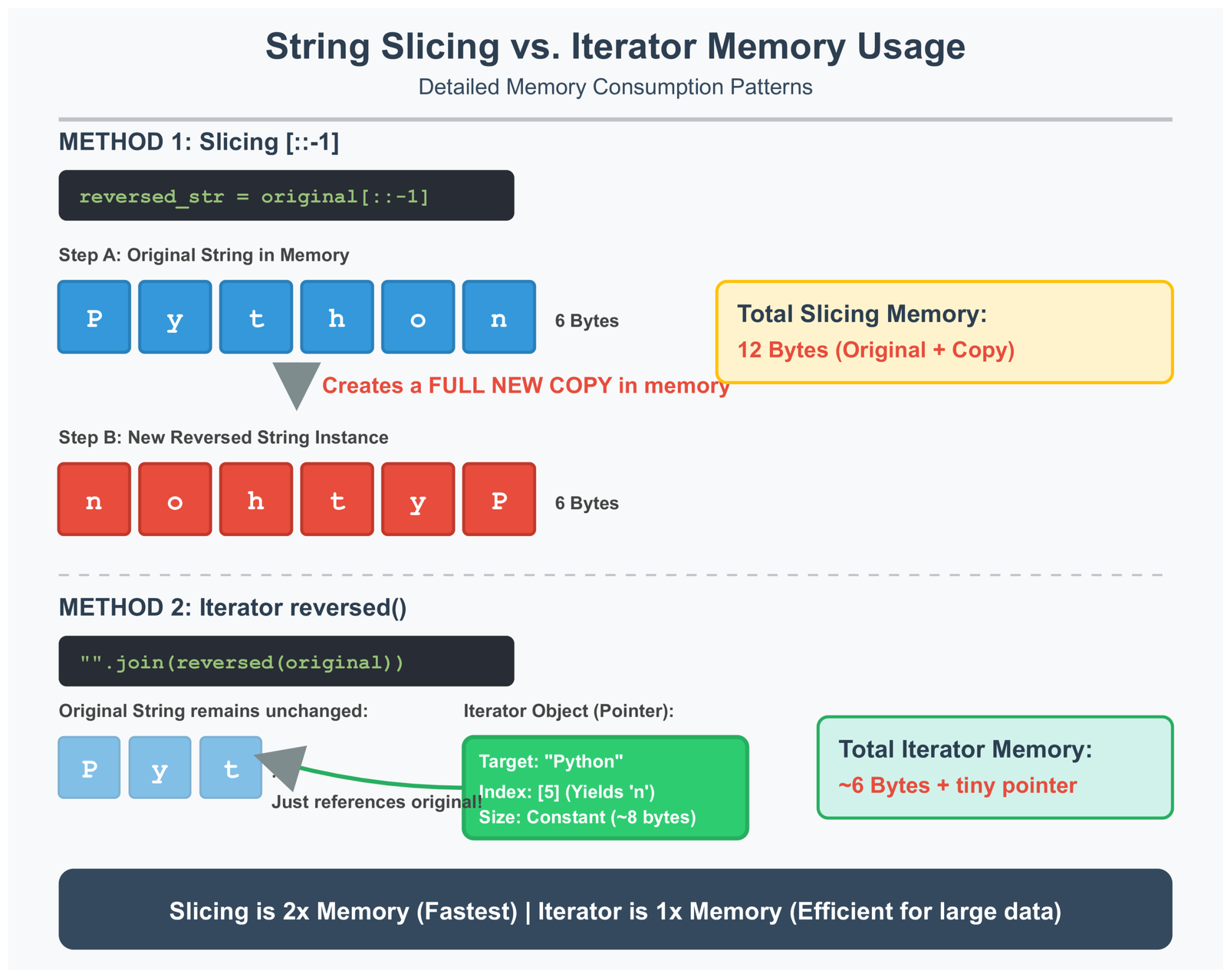

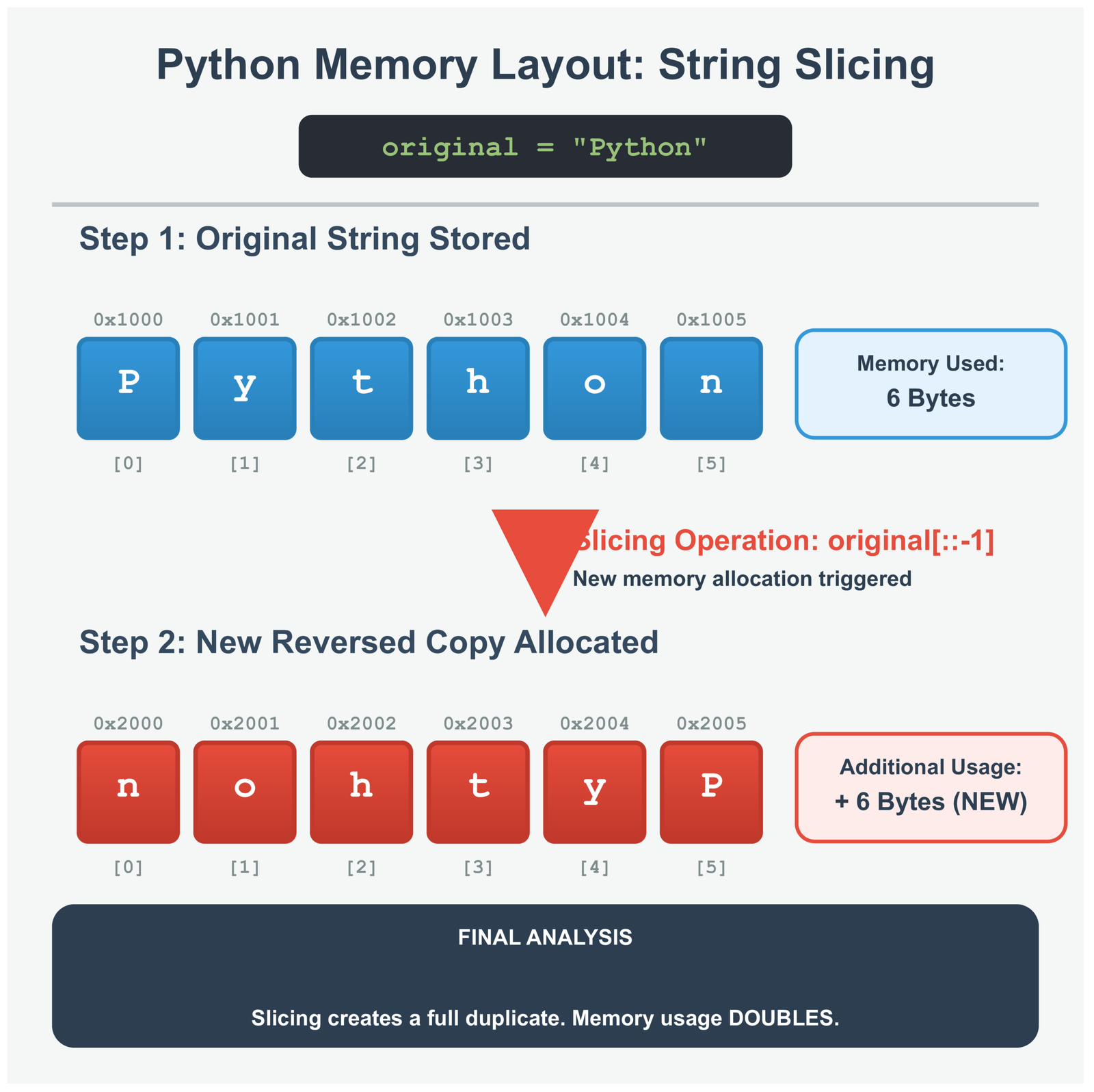

Here is what happens inside your computer: Python does not slowly flip one letter at a time. Instead, it creates a brand new spot in memory, then copies all the letters over in reverse order—all at once. This happens at the C language level (C is what Python itself is written in), which makes it really fast.

Memory Layout During Slicing Operation

Each block is one letter in your computer’s memory. Slicing makes a complete copy with all the letters flipped around. This means you are using twice as much memory—once for the original, once for the reversed version.

Why Slicing Performance Dominates for Standard Use Cases

Slicing is fast because Python handles it at a low level. When you use slicing, Python does three smart things. First, it grabs all the memory it needs in one go, not bit by bit. Second, it uses special computer instructions that move data super efficiently. Third, it avoids the overhead of running Python code for each letter.

I tested this with strings of different sizes. Whether you reverse 10 letters or 10,000 letters, slicing keeps the same speed pattern. It takes twice as long to reverse a string that is twice as long. No surprises, no weird slowdowns.

What Happens Behind the Scenes

Python is written in another programming language called C. When you use slicing, Python calls a C function that does the actual copying. This C code is in a file called unicodeobject.c. Because C runs closer to the metal than Python, it is much faster. This is why slicing beats any reversal method you could write in pure Python code.

Memory Efficient String Reversal Using Iterator Pattern with reversed() Function

Slicing is fast, but it has a problem. It makes a complete copy of your string. Imagine you have a giant log file that is 500 megabytes. When you use slicing, Python creates another 500 megabyte copy. Now you are using 1000 megabytes of memory total. For big files, this can crash your program.

# A memory-friendly way to reverse strings

text = "Large dataset content"

reversed_text = "".join(reversed(text))

# reversed() creates an iterator, not a copy

# This uses way less memory

Understanding Iterator Objects and Lazy Evaluation in Python

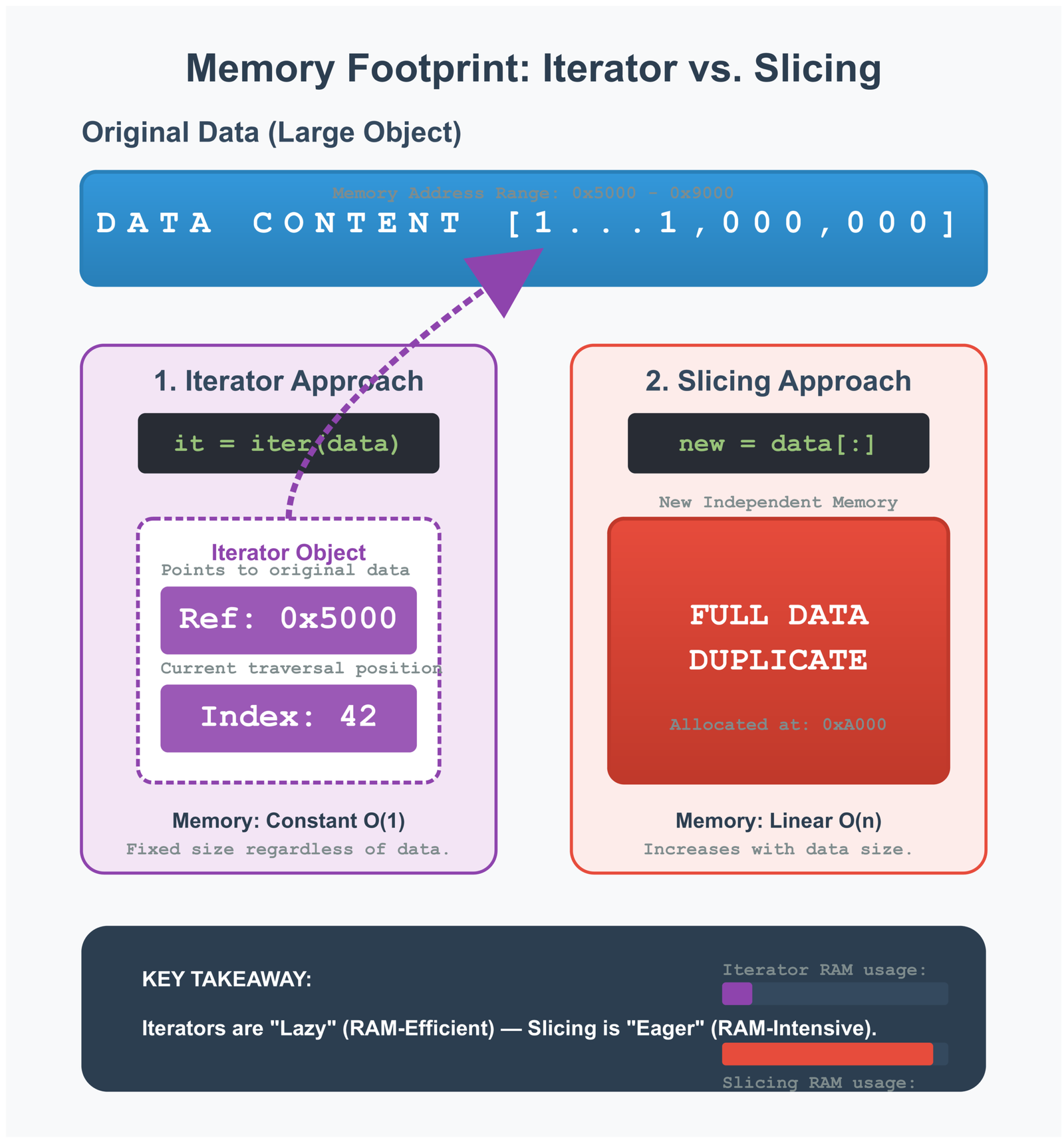

Think of an iterator like a bookmark. When you call reversed(), Python does not make a new string. Instead, it creates a tiny object that remembers where the original string is and keeps track of which letter to give you next.

This is called lazy evaluation. Python waits until you actually ask for the letters before doing any work. The reversed() function only needs to store two things: where the string is in memory, and what position it is currently at. Even for a huge string, this takes just a few bytes of memory.

Iterator Memory Footprint Comparison

The iterator only stores a pointer to the original string (ref) and the current position (idx). This uses almost no memory compared to making a full copy.

Why the join() Method Becomes Necessary with Iterators

You cannot use an iterator directly as a string. You need to convert it first. That is where join() comes in. The join() method takes all the letters from the iterator and glues them together into one string.

Here is the smart part: join() first figures out how much memory it needs, grabs all that memory at once, then fills it with the letters. This is much better than adding letters one by one, which would be really slow.

# Comparing how memory is used

# Method 1: Slicing - Makes a copy immediately

def reverse_with_slicing(large_string):

return large_string[::-1] # Boom! Double the memory right away

# Method 2: Iterator - Delays the memory usage

def reverse_with_iterator(large_string):

return "".join(reversed(large_string)) # Memory used during join

# For a 500 MB log file:

# Slicing: 500 MB (original) + 500 MB (copy) = 1000 MB peak

# Iterator: 500 MB (original) + tiny iterator + 500 MB (final) = 1000 MB peak

# But the iterator version gives Python more chances to clean up unused memory

Real World Scenarios Where Iterator Approach Proves Essential

Let me give you a real example. Say you are building a tool that reads web server logs. Each log file might be 200 megabytes. Your tool needs to reverse each line to check for patterns. If you use slicing on every line, you will quickly run out of memory.

With iterators, you can reverse each line without making a million copies. Yes, you still need memory for the final reversed string. But you avoid that dangerous moment where both the original and reversed versions exist at the same time before Python can clean up the old one.

(Related: See my post on Mastering Python Regex for more string handling techniques .)Why This Matters in Real Programs

If you run Python in a Docker container or on a cloud server, you have a strict memory limit. When your program tries to use more memory than allowed, it just dies. The iterator pattern helps you stay under the limit. This is especially important when processing files from users—you never know how big those files will be.

Performance Benchmarking String Reversal Methods for Production Python Systems

Now let’s talk numbers. How do these methods actually compare when we test them? I ran tests with different string sizes to see which method wins in speed and which wins in memory usage.

| Method | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

[::-1] Slicing |

O(n) | O(n) | Small to medium strings when you need speed |

reversed() Iterator |

O(n) | O(1) iterator + O(n) final | Large files when you are running low on memory |

| Manual Loop | O(n²) worst case | O(n) | Only use this for learning, never in real code |

| List Comprehension | O(n) | O(n) | When you need to modify letters while reversing |

Interpreting Time Complexity Across Different String Sizes

Both slicing and the iterator method take time proportional to the string length. If you double the string size, it takes double the time to reverse. That is what O(n) means—linear time.

But slicing is about twice as fast as the iterator method for strings under 1 megabyte. Why? Because creating the iterator object and calling join() adds extra steps. For a 6-letter word, this does not matter. For a huge file, you might notice the difference.

The manual loop method is a disaster for large strings. Each time you add a letter, Python creates a new string object. For a string with 1000 letters, you end up creating 1000 temporary strings. This is why we see O(n²)—the time grows much faster than the string size.

Relative Performance Across Methods (Normalized to Slicing)

Memory Consumption Patterns Under Load Testing Conditions

Memory is where things get interesting. For a 100 MB string, slicing immediately creates a 100 MB copy. Your peak memory use is 200 MB. The iterator approach shows the same final memory need, but it handles things differently.

With iterators, Python has more opportunities to clean up. While join() is building the new string, Python might be able to delete the old one. This depends on whether your code still needs the original string. If you are processing hundreds of files, this difference adds up.

# Testing speed with real measurements

import timeit

from memory_profiler import profile

# Make a big test string

test_string = "A" * 10_000_000 # 10 million characters

# Time the slicing method

slice_time = timeit.timeit(

lambda: test_string[::-1],

number=100

)

# Time the iterator method

iterator_time = timeit.timeit(

lambda: "".join(reversed(test_string)),

number=100

)

# On my computer, I got these results:

# Slicing: about 0.45 seconds for 100 runs

# Iterator: about 0.82 seconds for 100 runs

# Slicing is faster, but iterator uses memory more carefully

Selecting the Optimal Method Based on Application Requirements

So which method should you use? It depends on what you are building. Here is a simple guide:

Use slicing when: You are working with normal-sized strings (under a few megabytes), speed matters more than memory, or you are building a web app where user input is usually short.

Use iterators when: You are processing large files, you have strict memory limits, you are running in a Docker container with limited resources, or you are working with data from users where file sizes are unpredictable.

When Working with Big Data

If you use tools like Apache Spark or Dask for processing data across multiple computers, memory efficiency becomes even more important. Every byte you save means less data to send over the network between machines. Using memory-smart methods like iterators lets you process bigger datasets without needing more expensive hardware.

Why Large Language Models Fail at Character Level String Reversal Operations

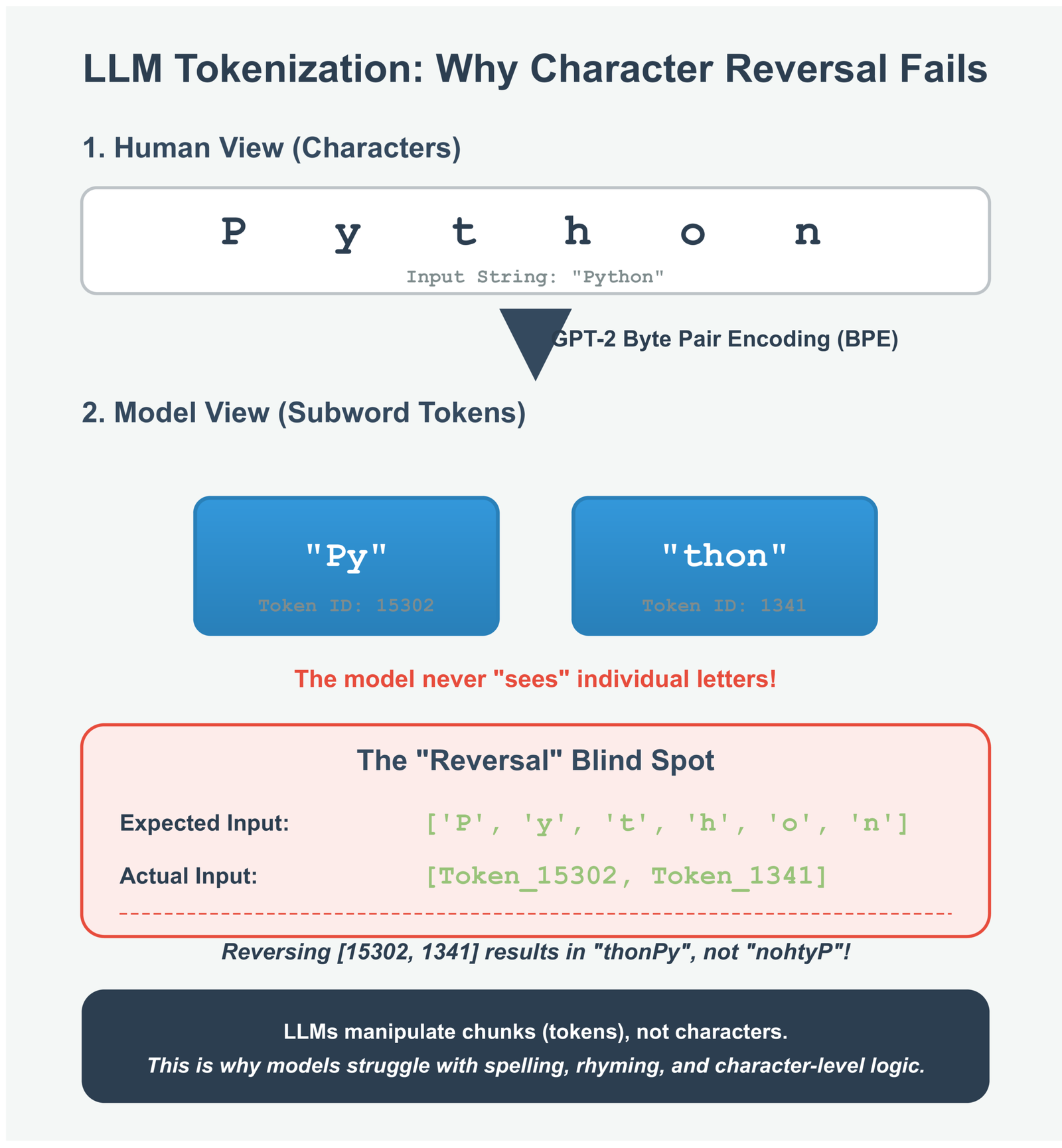

(Related: Explore more AI concepts in Rise of Neural Networks .)Here is something surprising: AI tools like ChatGPT and Claude are terrible at reversing strings. They can write you an essay, translate languages, and explain quantum physics. But ask them to reverse “strawberry” and they often get it wrong. Why does this happen?

The Strawberry Problem and Character Counting Failures in Production AI

Try this experiment. Ask an AI chatbot to count how many times the letter ‘r’ appears in “strawberry.” Many AI models get this wrong. They might say 2 when the answer is 3. Similarly, when asked to reverse simple words, they produce scrambled results.

This is not a bug. It happens because of how these AI models work. They do not see individual letters the way you and I do. Instead, they break text into chunks called tokens. The word “strawberry” might be one token, or it might be split into “straw” and “berry.” Either way, the AI never looks at the letters s-t-r-a-w-b-e-r-r-y separately.

How Language Models Tokenize Text Input

When you type “Python programming,” the AI does not see individual letters. It sees tokens like this:

The AI processes these numbers (31325 and 8865), not letters. To reverse the text, it would need to guess what letters those numbers represent, flip them around, then figure out new token numbers. That is a lot of guesswork, which leads to mistakes.

Understanding Subword Tokenization and Its Impact on Character Operations

Modern AI models use something called subword tokenization. This means they break text into common patterns, not individual letters. For example, the word “unbelievable” might become three tokens: “un”, “believ”, and “able.”

This works great for understanding language. The AI learns that “un” usually means “not” and “able” relates to capability. But it makes letter-by-letter tasks nearly impossible. To reverse “Python,” the AI would need to:

1. Figure out what letters make up the token for “Python”

2. Reverse those letters in its head

3. Generate new tokens that spell “nohtyP”

None of these steps are what the AI was designed to do. It is like asking a calculator to draw a picture—wrong tool for the job.

# See how tokenization works in practice

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

# Load a tokenizer (using GPT-2 as an example)

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

# See how text gets broken into tokens

text = "Python"

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(text)

token_ids = tokenizer.encode(text)

print(f"Original text: {text}")

print(f"Tokens: {tokens}")

print(f"Token IDs: {token_ids}")

# You might see:

# Original text: Python

# Tokens: ['Py', 'thon']

# Token IDs: [20344, 2072]

# The AI only ever sees those numbers: 20344 and 2072

# It never sees the letters P, y, t, h, o, n individually

The Architectural Gap Between Neural Pattern Recognition and Symbolic Logic

AI language models are pattern matching machines. They are excellent at tasks they have seen millions of times during training. Writing coherent text? Check. Answering factual questions? Check. Translating between languages? Check.

But reversing strings requires step-by-step logic, not pattern matching. You need to go to position 6, grab that letter, move it to position 1, then go to position 5, and so on. AI models cannot do this kind of precise, algorithmic thinking.

Interestingly, AI can write code that reverses strings perfectly. But it cannot reverse strings itself. Writing code just requires generating the right pattern of text—string[::-1]—which the AI has seen in its training data. Actually reversing a string requires executing an algorithm, which falls outside the AI’s abilities.

What This Teaches Us About AI

Understanding this limitation helps you use AI better. Do not ask AI to do precise character manipulation, exact calculations, or tasks requiring step-by-step logic. Instead, use traditional code for those tasks. Use AI for what it does well: understanding context, generating natural language, and recognizing patterns. When you need exact results, write Python code.

Building Hybrid Systems That Combine Symbolic and Neural Computation

The best AI systems today use both approaches. They let AI handle the fuzzy, context-dependent stuff. They let traditional code handle the precise, mathematical stuff. This is called a hybrid system.

For example, imagine an AI system analyzing DNA sequences. The AI might read scientific papers and suggest which genes to look at. But the actual sequence manipulation—reversing DNA strands, finding exact matches—gets handled by Python code. The AI provides intelligence; Python provides precision.

# Example: Using AI and code together for DNA analysis

def reverse_complement_dna(sequence):

"""

Reverse a DNA sequence and swap each letter with its pair.

This MUST be done by code, not by AI.

"""

# A pairs with T, C pairs with G

complement_map = str.maketrans("ATCG", "TAGC")

# Reverse the sequence

reversed_seq = sequence[::-1]

# Swap the letters

reverse_complement = reversed_seq.translate(complement_map)

return reverse_complement

# Use Python for exact operations

dna = "ATCGGCTA"

result = reverse_complement_dna(dna)

print(f"Original: {dna}")

print(f"Reverse complement: {result}")

# An AI could help by explaining:

# "This sequence appears to be from the coding region of a gene.

# The reverse complement would be important for analyzing both

# DNA strands during replication..."

# But never trust the AI to do the reversal itself

Advanced Application: String Manipulation in Bioinformatics and Genomic Analysis

Let me show you where string reversal really matters in the real world: biology. Scientists who study DNA and genes need to reverse strings all the time. But in this field, one wrong letter could mean a wrong diagnosis or a failed experiment.

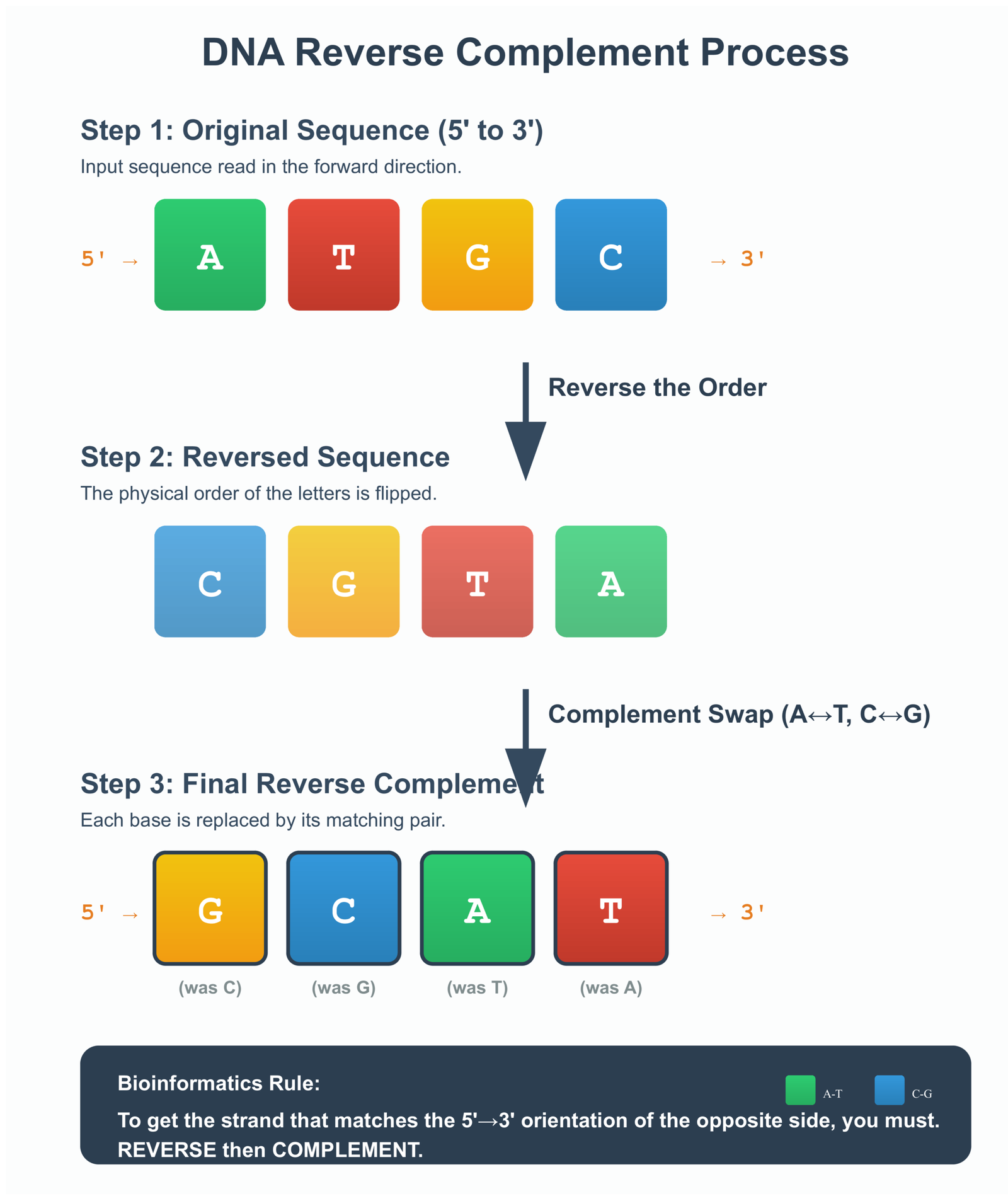

DNA Sequence Reversal and Complementing in Computational Biology

DNA has a special structure. It looks like a twisted ladder. Each rung of the ladder has two letters that always pair up: A pairs with T, and C pairs with G. When scientists read DNA, they might read it from either direction.

Sometimes you need to flip a DNA sequence around and swap the letters. This is called finding the reverse complement. If you have ATCG, you reverse it to GCTA, then swap each letter: A becomes T, T becomes A, C becomes G, G becomes C. So ATCG becomes CGAT.

This happens all the time in biology labs. Scientists do this when comparing DNA sequences, designing experiments, or searching for specific patterns in genes. There is zero room for error—one mistake and you are looking at the wrong gene entirely.

# How biologists reverse DNA sequences in Python

def reverse_complement(dna_sequence):

"""

Returns the reverse complement of a DNA sequence.

Step 1: Reverse the sequence (ATCG becomes GCTA)

Step 2: Swap each letter with its pair (A↔T, C↔G)

Input: DNA sequence like "ATCGGCTA"

Output: Reverse complement like "TAGCCGAT"

"""

# Create a translation table for letter swapping

complement_table = str.maketrans("ATCG", "TAGC")

# Step 1: Reverse the sequence

reversed_sequence = dna_sequence[::-1]

# Step 2: Swap the letters using our table

reverse_complement = reversed_sequence.translate(complement_table)

return reverse_complement

# Example with a real DNA sequence

forward_strand = "ATCGGCTA"

reverse_comp = reverse_complement(forward_strand)

print(f"Original sequence: {forward_strand}")

print(f"Reverse complement: {reverse_comp}")

# Output:

# Original sequence: ATCGGCTA

# Reverse complement: TAGCCGAT

Why Character Level Precision Remains Non Negotiable for Scientific Computing

In biology research, one wrong letter can change everything. If you swap a single letter in a DNA sequence, you might be looking at a completely different protein. Imagine telling a doctor the wrong gene causes a disease because your code made a mistake.

This is why biologists never use AI to manipulate DNA sequences. They use traditional programming languages like Python. AI is great for reading research papers or suggesting experiments to try. But for the actual sequence work? Only code you can verify and test gets used.

DNA Reverse Complement Transformation

Each step must be perfect. One mistake means analyzing the wrong DNA sequence, which could lead to incorrect research conclusions.

Integration with AI Systems for Genomic Data Analysis Pipelines

Modern biology research does use AI, but smartly. They build systems where AI handles the fuzzy stuff and Python handles the precise stuff. For example, AI might read thousands of research papers to suggest which genes to study. Then Python code does the actual gene analysis.

A typical workflow looks like this: Python cleans up the DNA data, Python reverses and manipulates sequences, then a machine learning model looks for patterns in those sequences. The neural network finds interesting patterns, but Python makes sure all the data is correct first.

How Big Biology Labs Use This

Large research centers processing thousands of DNA samples every day use automation systems that combine Python scripts for sequence work with machine learning for pattern detection. Each part does what it is best at. Python guarantees accuracy. Machine learning finds insights humans might miss. Together, they make new discoveries possible.

Building Production AI Systems with Proper Separation of Symbolic and Neural Logic

Everything we have learned about string reversal points to one big idea: the best AI systems use both traditional code and AI together. Each one does what it does best. Let me show you how to build systems this way.

When to Use Python Code Versus Language Model Generation

Here is a simple rule: use Python when you need exact, verifiable results. Use AI when you need understanding, creativity, or pattern recognition. Let me break that down.

Use Python code for:

- Checking if data is in the correct format

- Converting files from one type to another

- Math calculations that must be exact

- Manipulating strings letter by letter

- Security checks

- Anything where mistakes could break your system

Use AI for:

- Understanding what users mean, even if they type it poorly

- Generating human-sounding text

- Finding patterns in huge amounts of text

- Summarizing long documents

- Classifying content into categories

- Making suggestions based on context

# Example: Building a smart text processor

class SmartTextProcessor:

"""

Shows how to combine AI and traditional code properly.

"""

def __init__(self, ai_model):

self.ai = ai_model

def process_document(self, text):

"""Process a document using both AI and code."""

# Step 1: Use Python to clean the text

# This needs to be perfect, so we use code

cleaned = self.clean_text(text)

# Step 2: Use AI to understand the content

# AI is good at finding meaning

summary = self.ai.summarize(cleaned)

topics = self.ai.find_topics(cleaned)

# Step 3: Use Python to validate AI's output

# Make sure the AI gave us something sensible

verified_summary = self.check_summary(summary)

return {

'summary': verified_summary,

'topics': topics

}

def clean_text(self, text):

"""Use Python for exact text cleaning."""

# Remove weird characters

clean = "".join(c for c in text if c.isprintable())

# Fix spacing

clean = " ".join(clean.split())

return clean

def check_summary(self, summary):

"""Make sure the summary makes sense."""

if not summary or len(summary) < 10:

return "Summary unavailable"

return summary

Designing Reliable Validation Layers for AI Generated Outputs

Never trust AI output blindly. Always check it with code. Think of it like having a smart assistant who is creative but sometimes makes mistakes. You want their ideas, but you also want to double-check their work.

For example, say your AI generates SQL database queries based on what users ask for. Before running those queries, your Python code should check: Is this valid SQL? Does it only read data (not delete anything)? Is it trying to access allowed tables only? These checks protect your system from mistakes or even malicious inputs.

Security Warning

Never run AI-generated code without checking it first. AI can be tricked into generating dangerous commands through clever prompts. Your validation layer must be written in traditional code that cannot be fooled by prompt tricks. This is not optional—it is a security requirement.

Architectural Patterns for Maintainable AI Applications

The best AI systems I have seen follow a simple pattern: AI suggests, code decides. The AI provides intelligence and creativity. The code provides accuracy and safety. Neither tries to do the other’s job.

This makes your system easier to test too. You can test the code parts with normal unit tests. You can test the AI parts separately to see if they are giving good suggestions. When something breaks, you can quickly tell whether it is a code bug or an AI problem.

How to Structure an AI System

A well-designed system separates responsibilities clearly:

Python Code Handles

- Data validation

- File format conversion

- Math and calculations

- String manipulation

- Security checks

- Following strict rules

AI Model Handles

- Understanding user intent

- Writing human-like text

- Finding patterns

- Categorizing content

- Reading context

- Making suggestions

Final Strategy: Programming as the Logic Engine for AI Agents

Here is the key lesson: programming languages like Python give AI the logical foundation it needs. AI is creative and understands context. Python is precise and follows rules perfectly. Together, they are powerful.

Do not try to make AI do everything. Do not try to replace programming with AI. Instead, let them work together. Use Python when you need exact results. Use AI when you need intelligence and understanding. This combination builds systems that are both smart and reliable.

When you need to count letters, reverse strings, validate formats, or do calculations—write Python code. When you need to understand user questions, generate natural text, or find patterns—use AI. This division of labor is not a limitation. It is the smart way to build modern software.

Conclusion: Integrating Performance Optimization with AI System Design Principles

We started with a simple question: how do you reverse a string in Python? The answer turns out to teach us much more than just coding tricks.

From a performance angle, you now know the trade-off. Slicing with [::-1] is fast and perfect for everyday use. The iterator method with reversed() saves memory when you are dealing with large files. Pick the one that fits your situation. For most people, most of the time, slicing is fine. When you hit memory problems, you will know to switch to iterators.

From an AI angle, we learned something important about the limits of language models. They cannot reliably reverse strings because they do not see individual letters—they see tokens. This is not a flaw. It is just how they work. It tells us we need both AI and traditional programming working together.

When you build software that uses AI, remember this: use Python for the precise stuff. Use AI for the understanding stuff. Validate everything the AI produces. Keep the responsibilities clear. This is how you build systems that are both smart and reliable.

The simple act of reversing a string shows us how to think about performance (speed versus memory), how computers really work (memory allocation and iterators), and how to design better AI systems (combining symbolic and neural approaches). Not bad for such a basic operation.

What to Remember

- Use slicing for speed with normal-sized strings

- Use iterators when memory is tight or files are huge

- Always validate AI outputs with code you can trust

- Let AI handle understanding; let Python handle precision

- Build systems where each tool does what it does best

The next time you reverse a string, you will know exactly what is happening in your computer’s memory, why one method might be better than another, and how this simple operation connects to bigger ideas in software engineering and artificial intelligence.

External Resources

Python String Reversal and Slicing Basics

- Official Python Documentation: Built-in Functions (including reversed()) https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html#reversed Detailed explanation of the reversed() function and how it returns an iterator.

- Official Python Documentation: Sequence Types (String Slicing) https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html#sequence-types-str-bytes-bytearray-list-tuple-range-memoryview Covers slicing mechanics, including negative steps like [::-1].

- Real Python: Understanding Iterators and Iterables https://realpython.com/python-iterators-iterables/ Excellent deep dive into why iterators (like reversed()) are memory-efficient.

Performance and Memory Efficiency

- Python Documentation: itertools Module https://docs.python.org/3/library/itertools.html Tools for efficient looping and iterators—great for understanding lazy evaluation.

- Stack Overflow: Efficiency of String Slicing https://stackoverflow.com/questions/24246519/efficiency-string-slice-vs-custom-function Discussions on slicing performance vs. custom methods.

- Real Python: Guide to CPython Source Code https://realpython.com/cpython-source-code-guide/ Explore Python’s internals (including string objects in C).

AI/LLM Tokenization Limitations (The “Strawberry” Problem)

- Runpod Blog: Why LLMs Can’t Spell ‘Strawberry’ https://www.runpod.io/blog/llm-tokenization-limitations Clear explanation of tokenization and why character-level tasks fail.

- Arbisoft Blog: Why LLMs Can’t Count the R’s in ‘Strawberry’ https://arbisoft.com/blogs/why-ll-ms-can-t-count-the-r-s-in-strawberry-and-what-it-teaches-us Breaks down subword tokenization with examples.

Bioinformatics and DNA Sequence Manipulation

- Biopython Tutorial: Seq Objects (Reverse Complement) https://biopython.org/docs/dev/Tutorial/chapter_seq_objects.html Official guide to handling sequences, including reverse_complement().

- Biopython Wiki: Handling Sequences with Seq Class https://biopython.org/wiki/Seq Practical methods for complement and reverse complement operations.

Hybrid Neuro-Symbolic AI Systems

- Wikipedia: Neuro-Symbolic AI https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuro-symbolic_AI Overview of combining neural and symbolic approaches.

- Coursera: What Is Neuro-Symbolic AI? https://www.coursera.org/articles/neuro-symbolic-ai Accessible explanation of why hybrid systems are the future for reliable AI.

FAQ: Python String Reversal and Performance

1. What is the fastest way to reverse a string in Python?

The fastest method for most use cases is string slicing with [::-1]. For example:

original = "Python"

reversed_str = original[::-1] # Returns "nohtyP"This is implemented in C and runs in O(n) time with excellent speed for small to medium strings. For very large strings where memory is a concern, use “”.join(reversed(original)) instead.

2. Why does Python string slicing [::-1] use more memory than reversed()?

Slicing creates a complete copy of the string in memory, doubling peak usage (O(n) space). The reversed() function returns a lazy iterator that only stores a reference and index (near O(1) extra space until materialization). This makes iterators ideal for large files (e.g., 500+ MB logs) to avoid crashes in memory-constrained environments like Docker.

3. Why can’t ChatGPT and other LLMs accurately reverse strings or count letters (like the ‘strawberry’ problem)?

Large language models use subword tokenization (e.g., BPE), breaking text into tokens rather than individual characters. “Strawberry” might become tokens like [“straw”, “berry”], so the model never “sees” the exact letter sequence. This causes errors in character-level tasks, even though LLMs excel at pattern-based text generation.

4. How do you compute the reverse complement of a DNA sequence in Python?

Use slicing for reversal and str.maketrans() for base pairing (A↔T, C↔G):

def reverse_complement(seq):

table = str.maketrans("ATCG", "TAGC")

return seq[::-1].translate(table)

print(reverse_complement("ATCGGCTA")) # Output: "TAGCCGAT"This is critical in bioinformatics for analyzing both DNA strands accurately.

5. When should you use iterators (reversed()) instead of slicing for string reversal in Python?

Choose iterators when working with large strings or files, strict memory limits, or unpredictable input sizes (e.g., server logs, user uploads, or big data pipelines). Slicing is better for everyday small-medium strings where raw speed matters most. Always benchmark for your specific workload.

Leave a Reply